When My World Was Young 1945-56 The Yellow Brick Road 1956-60

What a Wonderful Town 1960-61

Wonderful Town (pt. II) 1962-66 The Gay Sixties 1966-70

The Juicy Life 1971-76

Juicy Life (pt. II) 1976-80

Losing Alexandria 1981-87

The AIDS Spectacle

Losing Alexandria (pt. II) 1987-1990's

WHAT A

WONDERFUL

TOWN!...?

1960 - 1961

...is there really something left after the daily drubbing of the job, where whatever it is we've all produced stacks up here against the sky, looming over us in the traffic and exhaust to leave us, at best, an edgy, dangerous glamour, a hatbrim slant romance. See? You're feeling that New York way again....

Okay, let’s sing us one of the old songs: It’s a hard, tough town, too heavy to pick up and run with and way too big to move with whatever muscle life has left you with this week. Should you take up smoking Luckies? What time is it? What decade have you landed in tonight? What’s your most essential name and what’s your function here? Is it Walk or Don’t Walk, Uptown or Down, the real world or just one more astral fantasy? Some nights are so confusing it gets too hard to tell.

Rafi Zabor

(author of The Bear Comes Home)

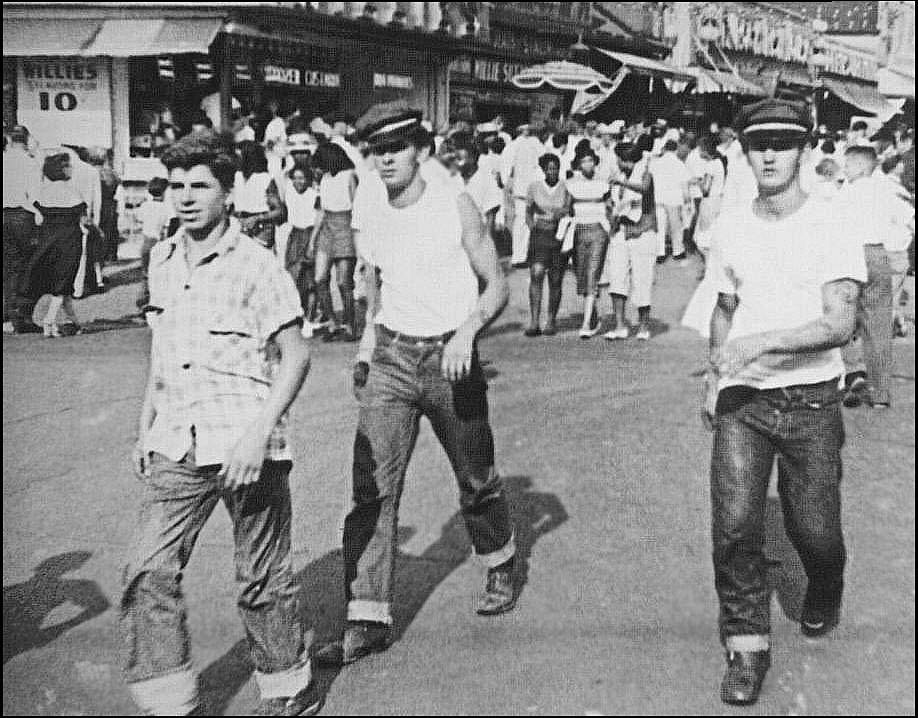

Sailors in Times Square, early 60s (photo: Edward Melcarth)

I had $50.00 in my pocket and a new suit when I

stepped off the Greyhound bus in New York. Both parting gifts from my

parents. There's an irony in this if you're familiar with Forties gangster

films: When prisoners finished their sentences and were released from the pen

they got fifty bucks and a new suit of clothes from the State. I felt that

was an entirely appropriate coincidence.

New York wasn't popularly the Big Apple in June1960, though it had been called "the Apple" as early as 1907. Sometimes it was Gotham, but that was sounding as dated as Damon Runyon. Sometimes it was the Big Town, but usually it was just "the city," but like The City, and even native New Yorkers meant Manhattan when they said it. But New York hadn't quite become the picture that sticks in my mind now, when I arrived it was still an old black and white movie in many ways.

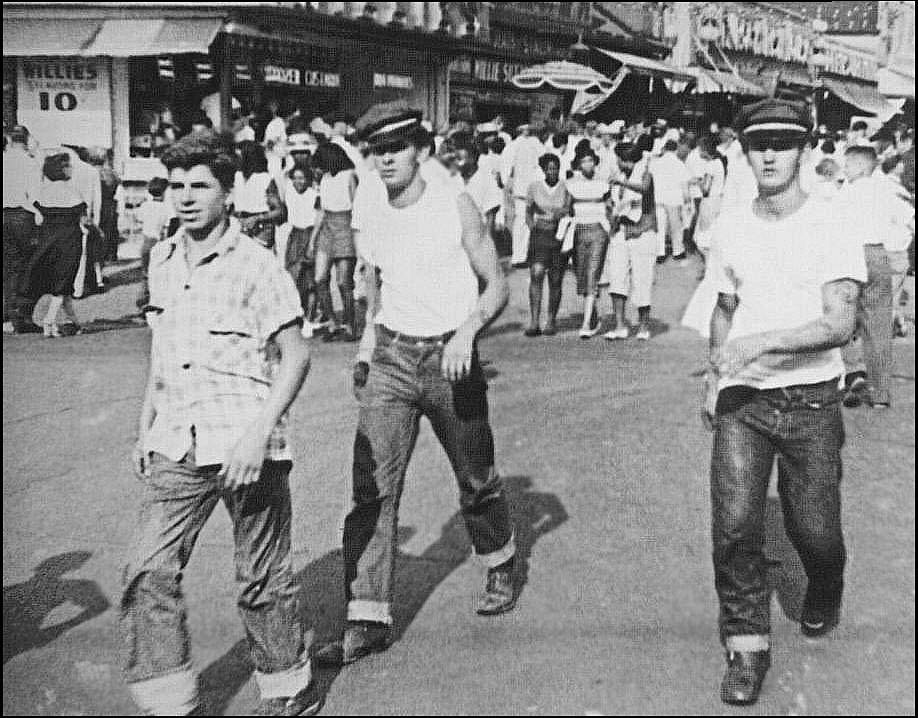

A 1963 Miss Subways

The

Yankees were playing ball in their stadium in the Bronx, even if the Dodgers and

the Giants had skipped town. Ever since 1941 you could "Meet Miss Subways"

each month as a new young female subway rider was

selected to have her photo and a bio on a poster in the trains, publicity shots

at the turnstiles - maybe hiking her skirt to show her "gams" - and thirty days

of fame and glory as the First Lady of the republic of the IRT/BMT and

The

Yankees were playing ball in their stadium in the Bronx, even if the Dodgers and

the Giants had skipped town. Ever since 1941 you could "Meet Miss Subways"

each month as a new young female subway rider was

selected to have her photo and a bio on a poster in the trains, publicity shots

at the turnstiles - maybe hiking her skirt to show her "gams" - and thirty days

of fame and glory as the First Lady of the republic of the IRT/BMT and

IND..."Change at Times Square/42nd Street for the Shuttle."

IND..."Change at Times Square/42nd Street for the Shuttle."

"My beer is Rheingold - the dry beer" was the New York beer drinkers anthem, and it was cheaper than the national brands (...except that a six-pack of Kreuger's on sale always undercut it.) And each year, beginning in 1939, a beautiful and busty new Miss Rheingold was selected - probably more New Yorkers recognized her than knew the current Miss America.

(right) Jinx Falkenburg, the first Miss Rheingold

Both Miss Subways and Miss Rheingold disappeared from city life in the 70's.

My beer is Rheingold, the dry beer

Think of Rheingold whenever you buy beer

It’s refreshing, not sweet

It’s the extra dry treat

Won’t you try extra dry Rheingold beer?

But Lever House, the glass-walled skyscraper that housed the Lever Brothers Corporation had gone up on Park Avenue in the early Fifties and knocked the socks off of just about everyone.

Lever House, the grandmother of all glass box skyscrapers.

All of the "els," the elevated subway lines, south of Harlem had been torn down. Third Avenue was open to the sky at last: goodbye to the atmosphere of Lost Weekend; hello, high rent Silk Stocking District. By '60 the let's-knock-it-all-to-the-ground-and-start-over juggernaut was getting up a good head of steam. The new Seagram Building was the glory of Park Avenue, and it's restaurants - the Brasserie and the Four Seasons - became in places to go. The Guggenheim Museum, looking like a snail shell disguised as a funnel, had opened and caused as much of a buzz as its collection. For those not of Four Seasons' caliber Top of the Sixes at the new 666 Fifth Avenue was the place to dine while looking down on Central Park. And the West Village was being studded with expensive high rise apartment buildings that were killing the old bohemian neighborhood.

However, block after block of midtown avenues on both the

East and West sides were still lined with late 19th and very early 20th century

buildings; much of the housing in Manhattan was the old brownstones and

tenements. West of Hudson Street in the Village was nowhere, and no one went

into Central Park after dark except for a risky blow job. The Beaux Arts beauty

of Grand Central Terminal straddled Park Avenue at 42nd Street uncontested

splendor, and

what will always be "the old Penn Station,"

a huge classical building derived from the Baths of Caracalla, stood just south

of West 34th Street. And the "best people" still stayed at the Plaza Hotel

or the Pierre at the southeast corner of Central Park. The

Metropolitan Opera House was on West 39th Street, (Lincoln Center was a

neighborhood of slum tenements made famous as the location shots for West

Side Story); Madison Square Garden was on 8th Ave. and 50th Street.

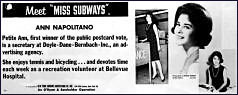

Dining at the Automat

The nearest thing to "fast food" was the soon to vanish string of Automats, or Bickford's cafeterias. The Prexies chain offered the "Hamburger with a college education." Delicious! Lower on the price scale the White Castles cooked up fast - and square-shaped - burgers. Also delicious! The Nedicks chain was for franks (hot dogs.) Orange Julius stands featured a concoction of orange juice and milk that gave the places their name, or for fifteen cents you could have a tropical drink at Grey's Papaya or one of its rivals. Ladies patronized the decorous Schraffts establishments, which seemed to hire their staffs "right off the boat from Ireland" as people often observed. "Meet me at Original Joe's"...meant a straight inexpensive Italian joint on Third Ave. in midtown which was a gay favorite. It became "Original Joe's" when another restaurant opened only a few doors away, using the name Joe's in attempt to get a free ride on their reputation. Pam-Pam, a little burger restaurant on Sheridan Square was a gay institution, though the Riker's burger joint across the street was packed with gay guys in the early morning hours.

At night the Great White Way was bright, but certainly not white. New York street lights gave off a yellowish light which lit a fairly small area. On major arteries store windows, bars and restaurants and advertising signs, as well as the headlights of motor traffic, increased this to a kind of splotchy brightness. Otherwise the streets could be heavily shadowed, and dark enough in many places to make walking hazardous - or dangerous. Long stretches of the streets looked worn and tired, and gusts of wind blew gritty dust through them so bad that many New Yorkers wore sunglasses as a defense not an affectation. The crumbling West Side Highway, elevated several stories above ground on decaying girders and dropping pieces of itself along the way, was a broad path of gloom and noise that wound down the entire length of the island along the Hudson shore.

Big comfortable Checker cabs plied the streets, and

were the preferred taxi. But buses were old and falling apart inside and out,

and the bus stops were farther apart then.

Big comfortable Checker cabs plied the streets, and

were the preferred taxi. But buses were old and falling apart inside and out,

and the bus stops were farther apart then.

(left) Early

60s bus;

(right) Interior of IND line

subway car, early 60s

Subway stations were grimy, stunk of piss and were furnished with wooden benches. If the buses were old the trains were ancient. (But for 15 cents....who's complaining?) The subway cars were an appropriate olive drab or battleship grey, the seats were often covered in woven cane varnished to a fare-thee-well or in plastic "leatherette," in either case usually worn, torn or slashed, and small fans circulated the air spasmodically, at least those that worked did. The doors between cars were often left open for ventilation, sending pages from discarded newspapers flying through the air while bottles rolled back and forth on the floor. Derelict drunks sacked out on the trains for the night.

Gypsy and

Westside Story were the established Broadway musical hits. Bye Bye,

Birdie had just opened. Jason Robards was in The Ice Man Cometh.

(JFK would be elected president in November, and the musical Camelot

would open in the fall and become the nickname for the era.) Old glamour

spots like El Morocco and the Blue Angel were there for the upper crust.

The less affluent could still go to the Roseland ballroom, and much farther down

on the scale was the Tango Palace on Broadway, where men could buy tickets

to dance with a staff of "taxi dancers." (Yes, the world of Ten Cents a Dance

and Private Dancer was still doing business. And here's a ticket

from '61 or '62.)

Gypsy and

Westside Story were the established Broadway musical hits. Bye Bye,

Birdie had just opened. Jason Robards was in The Ice Man Cometh.

(JFK would be elected president in November, and the musical Camelot

would open in the fall and become the nickname for the era.) Old glamour

spots like El Morocco and the Blue Angel were there for the upper crust.

The less affluent could still go to the Roseland ballroom, and much farther down

on the scale was the Tango Palace on Broadway, where men could buy tickets

to dance with a staff of "taxi dancers." (Yes, the world of Ten Cents a Dance

and Private Dancer was still doing business. And here's a ticket

from '61 or '62.)

Amato Opera, 107 seats Sammy's Bowery Follies

(photo: Weegee)

Sammy's Bowery Follies

(photo: Weegee)

Sammy's Bowery Follies with its cast of Skid Row performers was still in business too. And the plebes could see scaled down grand opera sung by unknowns in the tiny Amato Opera in the same tenderloin neighborhood. "The Crossroads of America": Times Square and West 42nd Street ("the Deuce")? It was a combination carnival and trash barrel, but heading straight for hell.

Regardless of what I knew from newspapers, magazines and television, those night-long rides on the Greyhound bus in the spring of my Junior year had been taking me to a New York made up of images my imagination had clipped from those great musicals On the Town and Wonderful Town. I was going to a rambunctious, music-filled, vividly colored Hollywood spectacle - and with the initial sightseeing and gawking during the day, and the rushing from bar to bar in taxis at night it had seemed very much like that. But what I'd learned while living in the city with Bob Manahan the summer of '59 toned the picture down a bit. However, after I returned to college in September for my senior year, sometimes - especially while listening to a couple of current Broadway show albums - I did slide back sometimes into those old technicolor fantasies.

However, later that fall word of the anti-gay campaign in New York dimmed them rapidly. Each new report of the relentless sweep of this crusade made it harder to believe I had once imagined New York as a distant outpost of European urbanity and tolerance toward homosexuals - a fiction in its own right, of course. And I had to accept that my narrow escape in the Mais Oui raid was the nasty real deal, and not a giddy caper.

.jpg) After

graduation I had returned to my hometown. My parents had it planned out

that I would find a job in nearby Rochester and live with them, and their agenda

was clearly to maintain total vigilance and control over my life. There

was no way I could acquiesce, and the tremors of a coming eruption got stronger

each day. One morning, after an argument with my mother, she abruptly said

that the only way I could avoid a fist fight with my father would be to leave.

But I was broke: and so I received a new suit and a fifty dollar subsidy.

These were bestowed with ardent ill wishes for my failure in New York, and a

thundering pronouncement that when I called up in a week or two begging for

help, I would be fetched then to return "home" and from then on I would do exactly

what I was told - if I knew what was good for me.

After

graduation I had returned to my hometown. My parents had it planned out

that I would find a job in nearby Rochester and live with them, and their agenda

was clearly to maintain total vigilance and control over my life. There

was no way I could acquiesce, and the tremors of a coming eruption got stronger

each day. One morning, after an argument with my mother, she abruptly said

that the only way I could avoid a fist fight with my father would be to leave.

But I was broke: and so I received a new suit and a fifty dollar subsidy.

These were bestowed with ardent ill wishes for my failure in New York, and a

thundering pronouncement that when I called up in a week or two begging for

help, I would be fetched then to return "home" and from then on I would do exactly

what I was told - if I knew what was good for me.

I had never before taken the trip to New York in such a sober mood. I knew beyond a doubt that the knowledge of my being gay had cut me off irrevocably from my past roots - not least my family; and this trip was a flight from retribution, even if it was no longer the journey to a gay utopia.

Pavement level reality when I stepped off the bus in June 1960 had nothing in common with verve and joy of On the Town. One of the most popular shows on television in these years was the Naked City series (1958 - 63) set in New York. It was based on Jules Dassin's 1948 award-winning movie of the same name, and the film's noir style had been inspired by New York photographer Weegee, who had published a book of photos of New York life called Naked City in 1945. That atmosphere was successfully carried over into the TV series. And though the city was changing, on the whole the gay life I would experience my first few years in New York had that same black and white underworld atmosphere: it was a brittle and threatening world, where glancing over your shoulder became a reflex.

On March 14, 1960, the New York Times ran an article, “Life on W. 42nd St. a study in decay.” I missed it; however, the Times itself would soon provide me with a paid education on the topic, and ultimately leading to a brief role as part of that decay.

THE PURGE

This era, had begun with the Lee Mortimer crusade in the Mirror in late 1959, and ran on with little respite to the end of the administration of Mayor Wagner, whose last term in office ended in 1965. It was a bleak and paranoid period of gay life in the city. (My own view of these years, though, is that they were also the prolonged death throes of the 50's.) Several influences contributed to the official anti-gay campaign, most of them having to do more with the vagaries of local politics, in my estimation, than with any general moral outcry.

(right) Mayor Robert Wagner

(right) Mayor Robert Wagner

Perhaps this is demonstrated to some degree by remembering that these same repressive years also encompassed the period of the great civil rights campaigns of the 60s, the presidency of John F. Kennedy (1960 - 63), whose style and programs brought an excitement and glamour into national life after the staid Eisenhower era (1952 - 1960), and the emergence of the Hippies.

New York like a number of other cities in the United

States had been controlled by a party machine, many of these had

their origins in the post Civil-War era. The northeast of the U.S. had become a

stronghold of the new Republican party under Lincoln. The only way the

Democratic party was able to lose its party-of-the-Rebellion stigma and regain

political influence was to woo the successive waves of European immigrants who

were arriving here. Over the decades these machines evolved as powerful forces

in the life of many major cities, becoming sources of patronage, a place for

grievance and redress and avenues to power for the new arrivals. In NYC the

Democratic party machine was known as Tammany Hall.

Though its influence had waned in the late Thirties and the Forties, it had been revived under the leadership of Carmine DeSapio in the Fifties, a departure from its history of Irish bosses. Tammany was again a potent power able to control and deliver many thousands of votes, but it was marked by dubious dealings and connections as well. Opposed to Tammany Hall were the emerging Reform Democrats who espoused more liberal social policies and party politics free from the manipulation and corruption of the Tammany machine. Any Democrat who wanted to be mayor in New York City in this era had to keep and eye on both of these camps if he wanted to ensure his election. There were shadowy connections involving Tammy Hall; racketeers from the various crime syndicates ("families") -- Italian; the waterfront racketeers - often Irish; and the police force - heavily Irish and Italian in makeup. Mayor Wagner had eased himself away from Boss DeSapio, and escaped being dragged down with DeSapio and Tammany Hall in the Sixties. What this meant in practical terms was that Wagner had adroitly balanced reform and the appearance of clean government, which appeased Jewish and WASP Reformers, with a day-to-day system of government that did not alienate the Tammany Hall faithful, largely working class and Catholic.

One easy scapegoat in any red herring "cleanup" campaign was the gay population. (The other was prostitutes.) Raids on gay bars and meat racks could be purveyed to the press and voting public as part of a campaign against crime and vice with no fear of alienating anyone. It also spotlighted the police as guardians of the moral order, and helped deflect the frequent charges of corruption and bribery which were leveled at them. It was a diversionary tactic that helped the Wagner administration (and certainly the police force) present itself as the enemy of crime and corruption in a very handy manner without in fact doing anything very substantive about either.

Most gay bars and restaurants were operated by the

Mafia, or under their "protection." (Rumor was that the profits from this

activity helped finance the emerging heroin trade.) Bribes were paid to

the police, which meant most of the harassment was directed onto the patrons and not

the establishments themselves - until such time as circumstances dictated that

a bar had to be closed. Wagner's cleanup campaign disturbed this

lucrative arrangement. However, it was better to have this action in the

hands of the police than in those of some special commission, which might do

permanent or long-term damage to the status quo and expose scandalous ties

between government and crime into the bargain. A current

Broadway

musical,

Tenderloin, was based on one such period of sweeping moral reform - and its

predictable failure, and another musical, Fiorello, dealt with political corruption in

pre-WW II New York. And now, once again, the same old, same old - the more things change...etc.

However, Wagner also became increasingly focused on making New York squeaky

clean for the approaching 1964 World's Fair.

Broadway

musical,

Tenderloin, was based on one such period of sweeping moral reform - and its

predictable failure, and another musical, Fiorello, dealt with political corruption in

pre-WW II New York. And now, once again, the same old, same old - the more things change...etc.

However, Wagner also became increasingly focused on making New York squeaky

clean for the approaching 1964 World's Fair.

Thus, for the Mafia and the police it was a matter of playing a waiting game until the politicians - and the press and public - lost interest. In the meantime, gay social life was ground to pieces by these forces - none of which would have seen this in anything less than a positive light whatsoever. While the atmosphere of illegality and the threat of punishment hung over gay life in the normal course of things, at this juncture the threat of force was actualized in an ongoing repression of gay life that to some degree affected almost everyone gay. It was not a matter of a couple of "tea room queens" being entrapped by a plainclothesman, or a few bar patrons being hassled in a raid, this time the clear intent was to close down public gay life across the board. Gay life for the next few years was to be an oftentimes dreary game of hide and seek. There would be moments when Syracuse would almost seem like a paradise lost in comparison.

BACK TO THE KID WITH A SUITCASE

My first stop was the West Side Y (West 63rd &

Central Park West), which was notorious as a place to cruise, and was virtually

a gay hotel - though the management quietly did everything they could to put the

clamps on both. I'd been warned by Bob to be very careful about what I did

there. Consequently, I was very aloof, and my impression in any case was that

gay guys were being extremely cautious about any "action." The main draw for

me though was that it was cheap and clean, and in a nice neighborhood on the

edge of Midtown. After a week I moved to the Sloan House (YMCA) on West 34th

Street and 9th Ave, which was slightly cheaper, though in a somewhat sleazy

neighborhood. It had the same reputation as having been a wild place for

pickups until very recently.

On my first day there I was taking a shower alone when someone came in and used the sinks around the corner. Before he left he peeked into the showers. A minute later a dark-haired guy with a gym-built body (these were not a dime a dozen in 1960) came in to take a shower. He was extremely chatty and in less than a minute invited me to his room - though with the proviso that I go get dressed first and then come to his room. (This I learned later was so you didn't get caught in someone's room without your street clothes.) When I got there I found that the first guy, who had checked out the shower, was there too. They were lovers, and the hunk was often used as bait to get a threesome - although in this case it didn't work as I said I "haven't done that yet" (though I have no doubt I would have if the first guy had appealed to me.) Nevertheless, the three of us went out that night to the Cherry Lane bar on Commerce Street (in the Village), and then to what was clearly a new venture as a gay bar, the Coral Lounge, just down the street from the Sloan House Y. These guys had been staying at the Sloan House for a couple of weeks, and warned me that employees patrolled the hallways wearing sneakers and listened at the doors if they thought guys were having sex.

I lucked out with a job. And I had to. As a college graduate I would be called up for a physical soon and be reclassified 1-A, prime draft bait; therefore, my chances of finding a job - especially as I needed one immediately - bordered on zero. Through a straight woman friend of Rob's that I'd met the past summer I managed to get a temp job at the New York Times News Service as a clerk/gofer for the summer.

Within a week or so, in a desperate effort to eke out a miniscule salary, I moved to Jamaica, a remote neighborhood in the outer borough of Queens. I got a room in the Jamaica Y on Parsons Blvd., at what for me was significantly less money than I'd been paying in Manhattan. Out there the gay life situation was even worse. There was one very small, dingy gay bar, the Bull's Head, which operated in an atmosphere of palpable tension on the part of both customers and management. Queens, even before the crackdown, had not been even remotely as open as Manhattan. Moreover, this bar wasn't in the Jackson Heights or Forest Hills neighborhoods, which at least had small gay populations -- it couldn't have hoped to be more than a quick-profit venture before getting padlocked.

My salary was very small, even for this era.

I could go to a bar and nurse a couple of beers for the evening, but after

paying for rent, meals, transportation and miscellaneous living expenses it

wasn't often that I got to do more expensive things. I do remember, though,

that one of the first things I did was buy a two-fer (half-price ticket) for a matinee performance of

Gypsy. I went by myself, so I got totally taken up in the performance

like probably never happened again. Later on this year I did get to

see Leave It To Jane at the Sheridan Square Theater, Off Broadway tickets

were considerably cheaper than Bway back then. It was a revival of

a Jerome Kern 1917 musical with a very thin story and silly dialogue and humor,

and it was too big a stretch for my limited experience to appreciate - except for

Dorothy Greener's performance, especially her number "Cleopatterer."

(Dorothy was an excellent comic actress, and she used to come to the Five Oaks

often when I went there much later in the Sixties.)

When I'd arrived at the beginning of summer I found only two bars left open out of the more than two dozen from the previous year, the Cafe De Lys and the Cherry Lane, which were about a block from each other in a then very quiet part of the Village just east of Hudson Street. (Actually, west of Sixth Ave. the Village was a fairly subdued place overall, despite having many restaurants and bars.)

(right) Peter, the de Lys bartender

The de Lys, was the smaller place and its crowd was more relaxed. Its juke box had such an extraordinary menu of selections that it must have reflected someone's personal taste - choice jazz ballads and only the better pop music. I especially remember Etta Jones' (right, Etta Jones not Etta James) recording, Don't Go To Strangers. The de Lys also had an affable bartender, Peter, who had a beautiful gym-built bod, not by any means a common thing in these years.

The Cherry Lane bar was

a bigger, livelier place, and a few blacks and Hispanics were part of the regular crowd. It also allowed dancing from time to

time that summer, which was courting disaster, but perhaps it was a way of

trying to increase the profits while there was still time. The atmosphere

was not like a dinner dance with the upper level of the upper crust, by any

means.

The Cherry Lane bar was

a bigger, livelier place, and a few blacks and Hispanics were part of the regular crowd. It also allowed dancing from time to

time that summer, which was courting disaster, but perhaps it was a way of

trying to increase the profits while there was still time. The atmosphere

was not like a dinner dance with the upper level of the upper crust, by any

means.

Cherry Lane

Theatre (canopy), the doorway after the bench was the bar entrance,

building with the red awning was the Blue

Mill restaurant, popular with gay men.

One clique of regular patrons from the Village was inclined to exercise a kind of "ownership" of the place by being aggressively loud and campy. They are not to be imagined as posturing hot-house flowers, however, several were very husky guys. One of the latter was Hal, a big young man with a voluptuously handsome face, who delighted in throwing out bitchy put-downs and provoking confrontations even with total strangers. I remember one night when he baited a new customer, and after the second or third remark the guy wasn't having any, thank you. The guy's friends tried to restrain him, but Hal was in his glory and poured on the taunts. The guy broke loose, hit Hal with a volley of punches and decked him in a matter of seconds. All hell broke loose - shouts, curses, fists flying - and for a few moments this "fairy bar" looked a waterfront dive.

And then there was the Julius Bar - Julius's - on West 10th between Seventh Ave. and Greenwich Ave. in the Village, but it resisted with all it's might to keep from becoming an openly gay bar. Though it was a battle barely won, the management was unrelenting in its efforts no matter how many gay guys might patronize the place. I never felt really comfortable there as a result, but then that was their wish.

A FULL-TIME JOB AND "THE BOYS" FIND AN APARTMENT

At the end of the summer I was able to get transferred into the Times newsroom as a full-time copy boy. I worked at night, which was the peak time for the Times as it is a morning paper. At 3 a.m. subway service was as bad as it got: interminable waiting for the E train to Jamaica, and then the long ride out hitting all the local stops could add an hour and a half to the day. It also made having a social life in Manhattan a major problem. A trick I met in a bar invited me to stay at his place in Manhattan, a sparsely furnished apartment above Johnnie Johnson's nightclub on Second Avenue, and then after a month or so I got an apartment on West 81st and Amsterdam Avenue, on the Upper West Side, with Milton, a longtime friend of his who'd just arrived in town to try to make a life for himself as a pianist in show business.

Milton and I were shown the apartment by a Hispanic super, who took care of a bunch of buildings on a part-time basis - the radiators were stone cold on a bitterly cold November day (a harbinger of more of the same all winter it turned out.) We then were sent to an address on West End Avenue to see Mr. Goldman, the very appropriately named landlord. It was a large, old apartment where a Scrooge-like man sitting behind a huge desk in an otherwise unfurnished room, interviewed us as we stood before him. In closing he smiled and commented that he didn't mind renting to "boys like you," and he was sure we would make good tenants. I was to learn from a landlady later on that his attitude was a not uncommon sentiment amongst many Westside landlords: Better fags than Puerto Ricans and blacks. They didn't mind if you were "that way" if you were white, though gay Hispanics and blacks did seem to have a bit of leg up over their straight compatriots.

"BOYS"

The use of "boys" to characterize gay males was often used with the same condescending intent as when it was applied to black adult males.

Contrary to the 90's and after, when there would be an accepted Boy image that many men (straight and gay) would aggressively seek to emulate, and when adolescence would virtually stretch into the mid-twenties, no gay males in the Sixties strove to affect a Boy look or habits. You would have been taken for a total jackass. For one thing, the youth market and culture were in a nascent stage of development, and there was little, if any, ambivalence about the desirability of leaving the hallmarks of adolescence behind. "Maturity" was the constant injunction during high school years, and maturity was accepted and yearned for by kids as the Promised Land of privilege and independence. In the Fifties and early Sixties college students very self-consciously repudiated the music and dress of teenagers and created their own stereotype, which said young adult. The goal of young people in this era was to achieve adulthood, which meant freedom, increased status, access to money and power. Being designated a "boy" as an adult meant that in some ways you hadn't made it completely - most frequently, probably, in reference to being unmarried. (The expression "the boy's night out" pointed, even if veiled as humor, to married men acting retrogressively.)

Homosexuals were not only not real men, as "boys" they were not really adults either. And, of course, from there it was only a short step to "girls."

When the anti-gay columnist, Lee Mortimer, warned Allen's bar and restaurant and other ostensibly straight establishments about having gay customers, there was nothing neutral or unclear in his use of "the boys" in referring to gay men. Even when used by gay men, "gay boys," as far as I can recall was usually a put down. Many years later, in the mid-Seventies, I had a landlady who habitually referred to her gay male tenants and their friends as "you boys," a term I never heard her use with straight males tenants, even the single ones.

WEST SIDE

STORY

"...Moreover, this entire region [the Upper West Side] combines in its general

aspect all that is magnificent in the leading capitals of Europe...in our grand

Boulevard [Broadway] the rival of the finest avenues of the gay capital of

France, in our Riverside Avenue the equivalent of the Chiara of Naples and the

Corso of Rome, while the Beautiful 'Unter den Linden' of Berlin and the finest

portions of the West End of London are reproduced again and again."

Egbert L. Viele, 1879

NYC tenements, 20th century

The Upper West Side runs from Columbus Circle at the southwest corner of Central Park north to the vicinity of Columbia University, and is bounded by Central Park on the east and the Hudson River (and Riverside Park) on the west.

Today its gentrification is complete, but in 1960 it was just beginning. Generally speaking, its avenues were lined with large and often architecturally impressive apartment buildings, or shabby old commercial buildings and/or crumbling tenements - which depended on the particular avenue; while the streets were mostly filled with New York's famous brownstone houses, once private homes, but converted to small apartment buildings and rooming houses. (Note: In most of Manhattan the broad "Avenues" run north/south, whereas, the narrower "Streets" run east/west.) Other neighborhoods to the south of Manhattan's Upper West Side had their own names, e.g. Hell's Kitchen (in midtown), Chelsea (West 20's), Greenwich Village (below West 14th), etc.

With the general exception of the bohemian Village and Chelsea, the rest of the West Side - Hell's Kitchen and the Upper West Side - was very definitely not the place to live. On the other hand, a single guy living in the Village would be assumed a faggot. But with the demise of the Third Avenue el on the Upper East Side the gentrifying area from there to the river had become a very desirable neighborhood - and had the desirable telephone exchanges. In 1960 New York City telephone exchanges were still named, and exchanges were specific to neighborhoods. Thus, a Templeton 8 number indicated that you had an Upper East Side residence, so did Butterfield 8 (as in John O'Hara's novel of the same name.) Gay men looking for a safe, respectable address without tell-tale associations headed over there, especially those from white middle class backgrounds. And vest pocket neighborhoods farther south, such as Gramercy Park and Murray Hill were very desirable as well. They were something like "address insurance", and certainly a plus when you wanted to shoe-horn your (closeted) white middle class self into the New York Athletic Club.

The tenements on the west side of Broadway just above Columbus Circle in the lower Sixties (i.e., streets numbered West 60th through West 69th), the area where West Side Story was set, were being razed to make way for Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts. Passing by on the #11 bus, those gutted blocks reminded me of the newsreels I had seen as a child of bombed out London or Hamburg or Berlin. The idea that whole streets could be knocked down and all traces of their former appearance vanish, or in this case even the actual streets themselves disappear from the map, was still new to me.

Central Park West was the eastern boundary of the Upper West Side. It was

lined with opulent old apartment buildings, and for much of its length was still

a desirable and moneyed address. The avenue has buildings on its west side

only, which means they have an unobstructed view across the Central Park. The east

side of the street has just a sidewalk, and many trees and benches, and runs along the stone

boundary wall of Central Park. This side of CPW was also one of the city's

busiest meat racks and cruising areas at night from the mid-Sixties up to the

entrances to the park (and the area of the Rambles) at West 78th and 81st streets.

The western boundary of the Upper West Side, Riverside Drive, faced a lovely park and overlooked the Hudson River, and though it had seen much better days it was still considered a fairly decent, if deteriorating neighborhood. Parts of Riverside Park were also used as meat racks and pick-up areas at night.

(right) Soldiers and Sailors Monument

The Soldiers and Sailors monument in the upper 80's was notorious, but somewhat dangerous as young muggers sometimes descended on the place and picked off victims. West End Avenue, one block west of Riverside, was lined with large apartment buildings, much plainer looking than the grand ones on CPW, once fashionable but now faded and progressively more tired the further north you went.

Upper West Side

Houses, a majority the classic Brownstones.

Upper West Side

Houses, a majority the classic Brownstones.

While its east and west perimeters housed middle class and wealthy white people -

many of them Jews - and the offices of doctors and dentists, the broad central

section of the Upper West Side was inhabited by a mixture of far less affluent

folks. Between these outer avenues were Broadway, Amsterdam Ave. and

Columbus Ave. They and the streets which crossed them were an area which

ran a negative gamut from dingy to slum. Some of these were representative of the white ethnic families that had moved

into the neighborhood as it began its decline (Irish, German and East European Jews seemed to

predominate), but it had also attracted a newer population of non-ethnic whites

who earned small or precarious incomes, and last - in many respects - was the

very large minority of Hispanics and a smaller

number of blacks, who as groups were

certainly very poor.

(right) Hotel Lucerne, W. 79th & Amsterdam

And even in its glory days the Upper West Side had attracted actors, and the Lucerne Hotel on the corner of Amsterdam and 79th St. was where the famous actor, James O'Neil and his wife had lived for awhile, and where their son, Eugene O'Neil, later to become one of America's greatest playwrights, was born. The Lucerne was still there when Milton and I moved in two blocks away, but it had become a seedy dump with torn curtains and window shades flapping out the open windows, and tough looking men boozing on its front steps. (It has been refurbished and is once again a fine hotel.)

Verdi Square, 72nd & Broadway

Actors and dancers were part of the newer white population

which had

been attracted to the neighborhood because of its low rents, as well in their

case its closeness to the theatre district just west of Times Square.

However, the

Upper West Side itself had been part of the theatre neighborhood of the 1920's.

Shuffle Along, a black musical, opened on West 63rd Street and introduced

the hit song, "I'm Just Wild About Harry." Langston Hughes credited the show

with inaugurating the Harlem Renaissance. The Charleston, a dance craze of

that era, was first seen in a musical at the Colonial Theater at 63rd & Broadway

The famous Jazz Age madam Polly Adler moved into the apartment of a showgirl

on Riverside Drive and began running the first of her many classy bordellos.

Crime lords Meyer Lansky, Lucky Luciano and Frank Costello each lived in the

Majestic Apartments at 72nd and Central Park West for a time, and Costello was

gunned down in the lobby in a failed gangland assassination in 1957.

Shuffle Along, a black musical, opened on West 63rd Street and introduced

the hit song, "I'm Just Wild About Harry." Langston Hughes credited the show

with inaugurating the Harlem Renaissance. The Charleston, a dance craze of

that era, was first seen in a musical at the Colonial Theater at 63rd & Broadway

The famous Jazz Age madam Polly Adler moved into the apartment of a showgirl

on Riverside Drive and began running the first of her many classy bordellos.

Crime lords Meyer Lansky, Lucky Luciano and Frank Costello each lived in the

Majestic Apartments at 72nd and Central Park West for a time, and Costello was

gunned down in the lobby in a failed gangland assassination in 1957.

Later, author Ira Levin would set Rosemary's Baby (1967) in the neighborhood, and Roman Polanski would film the movie at the Dakota apartment building on W. 72nd St. & Central Park West.

Possibly the presence of gay theatre people (plus the low rents, of course) was what attracted other gay men to the neighborhood. As I was to learn over time, the Upper West Side seemed to have had a gay population whose history went back to the beginning of the Fifties and perhaps the Forties. The popular Cork Club bar had been located there in the early Fifties as well as the Verdi, both near Verdi Square at 72nd and Broadway; and in the late Fifties two popular dance bars, the 415 on Amsterdam in the lower 80's and the Mais Oui in the 60's near Broadway. The Central Park West cruising scene had been going on for years and was largely made up of local residents of various ethnicities.

Alan Helms, "Young Man from the Provinces" cover. Lou Degni (Mark Forrest) by Lon of NY.

The 50's/60's self-appointed Golden Boy of New York gay life, Alan Helms, began his

saga in the city on the Upper West Side. In 1957 the physique photographer

Alonzo Hannigan, known as Lon of New York, moved his studio to an

apartment on West End Avenue once occupied by Mae West, and after it was raided

by the police in 1961 he moved over to West 72nd Street.

The 50's/60's self-appointed Golden Boy of New York gay life, Alan Helms, began his

saga in the city on the Upper West Side. In 1957 the physique photographer

Alonzo Hannigan, known as Lon of New York, moved his studio to an

apartment on West End Avenue once occupied by Mae West, and after it was raided

by the police in 1961 he moved over to West 72nd Street.

The fall of '60 was very cold, and the winter was worse, and the streets often virtually empty. I still worked nights and slept days, my days off never included Friday or Saturday nights. I would run over to the 8th Ave. IND (subway) on Central Park West in the late afternoon, or catch a bus on Columbus for downtown if it wasn't too cold to wait in the open. In the early hours of the morning I hustled back from the subway as fast as I could, and the street lighting was so bad that it was pitch black in some places. As far as I knew there were no gay bars on the West Side, so I went to whatever part of town where I heard one had opened.

At one point that winter a powerful blizzard choked the city with drifts that brought traffic to a complete standstill and buried cars and sidewalks for days. The silence was eerie. I walked down the middle of Columbus Avenue to work as even the subways weren't running.

One

evening on my way to work I was almost alone on the IND platform, only two or

three other people waiting at a distance from me. I saw a train coming

down the tunnel, and the draft from it began to suck up trash and dust. I

heard footsteps on the stairs as someone raced down from the token booth to be

sure they didn't miss it. A man dashed onto the platform forty or fifty

feet from me and looked up the tunnel. The train had almost reached the

station. He jumped down onto the tracks, curled up on his side between the

rails and put his head on a rail, resting it on this folded hands. For

just a few seconds he looked like a child going to sleep. The trainman

slammed on the brakes, but it was useless. It was a short train that came

to a stop farther down the tracks. The man's body was almost in front of

me, his head smashed like a melon fallen off a truck.

One

evening on my way to work I was almost alone on the IND platform, only two or

three other people waiting at a distance from me. I saw a train coming

down the tunnel, and the draft from it began to suck up trash and dust. I

heard footsteps on the stairs as someone raced down from the token booth to be

sure they didn't miss it. A man dashed onto the platform forty or fifty

feet from me and looked up the tunnel. The train had almost reached the

station. He jumped down onto the tracks, curled up on his side between the

rails and put his head on a rail, resting it on this folded hands. For

just a few seconds he looked like a child going to sleep. The trainman

slammed on the brakes, but it was useless. It was a short train that came

to a stop farther down the tracks. The man's body was almost in front of

me, his head smashed like a melon fallen off a truck.

I

was the only witness. I was interviewed by the police at the scene...my

boss was pissed because I was late for work, never mind that I 'd seen some poor

wretch destroy himself; then later I was visited twice by officers from

different branches of the police department - my supervisor was steaming.

One of the late editions of the Times had a brief paragraph about

the

incident buried in the back pages. He had lived in a rooming house not far from

me: middle aged, no job, a name and an address - but no other personal

information was found on his body or in his room. I finished on the last

shift and got home after four a.m., about an hour later the phone wakes me:

it's a guy from the Transit Police! Could he stop by to interview me.

And it wasn't just the same list of questions yet again, but - sorry - I would

have to go down to the subway station and describe what happened at the

scene...so, about five a.m or five-thirty the two of us walked back in the

freezing ass cold to where my night, and nightmare had started. The

horrible scene, the guy's

anonymity have remained with me.

In this place where the sound

of sirens never ceases

and people move like a ghostly traffic from home

to work

and home,

and the poor in their tenements speak to their

gods....

Mark Strand

from Night Piece (after Dickens)

Except for ducking into a bodega (small Hispanic grocery) to buy something for breakfast, or maybe stopping at the all-night greasy spoon on the corner of Amsterdam & 81st to pick up a couple of burgers on the way home - and being aware that the customers were mostly Hispanic and black - I had seen almost nothing of the neighborhood I had moved into.

Then came a warm spring day. There were dozens

of people on the stoops of the tenements next door and across the street, people

hanging out the windows too and radios blasting salsa music (though I had no

idea what it was called.) I turned the corner onto Amsterdam Avenue and

stopped dead in my tracks. Here it was, just like the lyrics in Westside

Story, "Puerto Rico in America!" And the Dominican Republic and Cuba

and Haiti too. It was if someone had given the neighborhood a shot of

adrenalin: hundreds and hundreds of people...music, noise and

talking, yelling and fighting in Spanish and Creole...racks of clothes displayed

in front of stores and piles of merchandise on the sidewalk...

(right) Oshun, a Santeria orixa in her Christian guise

signs in Spanish advertising the services of lawyers, translators, diviners...little Hispanic eateries - comidas chinas y criollas and botanicas, which sold the paraphernalia of Santeria, the Afro-Latin religion. It wasn't entirely a pretty Caribbean travelogue for a callow recent college grad, however.

Burglary was endemic. Many apartment doors,

like ours, were fitted with "police locks" in addition to one or more regular

locks. These were thick iron bars that fitted into a metal slot in the

floor while the upper end leaned against the door and slid into a metal box in

the middle of the door about a third of the way up from the floor. They

were opened with a key that caused the bar to slip aside, letting you push the

door open. Without a key, kicking the door down and knocking it off its

hinges was the only way to gain entry. Windows often had security gates on them.

There was a darker side too: the incredible squalor, violence and murder of the

Endicott Hotel (now a classy condo), the dealers who melted into the doorways

when the cop cars cruised slowly down the streets, the gangs of brawling young

drunks that hung out on certain corners at night...narcotics and prostitution.

Coming home from work in the early

morning hours became scary now the weather was warm.

Burglary was endemic. Many apartment doors,

like ours, were fitted with "police locks" in addition to one or more regular

locks. These were thick iron bars that fitted into a metal slot in the

floor while the upper end leaned against the door and slid into a metal box in

the middle of the door about a third of the way up from the floor. They

were opened with a key that caused the bar to slip aside, letting you push the

door open. Without a key, kicking the door down and knocking it off its

hinges was the only way to gain entry. Windows often had security gates on them.

There was a darker side too: the incredible squalor, violence and murder of the

Endicott Hotel (now a classy condo), the dealers who melted into the doorways

when the cop cars cruised slowly down the streets, the gangs of brawling young

drunks that hung out on certain corners at night...narcotics and prostitution.

Coming home from work in the early

morning hours became scary now the weather was warm.

I'd never known any Hispanic people and had only a

vague academic knowledge of their cultures from sociology courses I'd taken. But

in the next few years Latino popular culture would become a familiar, if

secondary,

note in my life - and until the mid-Seventies salsa and merengue

were part of the background music of the neighborhood - and in both my personal life and at various jobs I would have

Hispanic friends and acquaintances, as well as sexual partners. However,

at this point I was encountering "Puerto Ricans" for the first time, and

these were the people that many (perhaps, most) whites considered the source of

everything that made the West Side a bad place. (White New Yorkers often lumped all

Hispanics together as "Puerto Ricans" at this time, those with more contempt

called them "Spicks" - from Hispanics I'm assuming.)

"What do they know about love uptown!?"

from Greenwich Village, U.S.A, which played at 1 Sheridan Square in 1960

(At this time the "uptown" being given a verbal sneer would have been the

Upper East Side.)

THE BARS

The De Lys and the Cherry Lane closed late in the year. (Julius's remained open and attracted a persistent gay clientele, however, it was an avowed straight bar whose temperature for gay men ran from unwelcoming to aggressively hostile.) The gay Finale restaurant - which may have actually been called the Grand Finale - managed to remain open throughout the years of harassment, perhaps because it attracted a very small and quiet bar crowd. (Anyway, it was too rich for my blood.) The gay bar scene remained furtive and unstable for years, marked by a series of short-lived places numbering in the dozens, without a doubt, if I could remember them all - Glennon's, 14th Street Cafe, 19th Street Cafe, Coronet, Bleecker St. Tavern, the Hat Box, the Campus, Jack & Nats and on and on. Usually no more than three were operating at the same time, often just two as far as I knew, and their life spans were sometimes counted in weeks - months if they were lucky. It went on like this for several years. Open/close, open/close, now here/now there. Though these places might be pretty crowded on a Friday or a Saturday night, considering that there were so very few open at the same time, most guys couldn't have been patronizing them. Socializing with friends and giving and going to parties played a much larger part in gay life than in later decades.

I was struck by the mix of guys in Glennon’s the first time I walked in. My impression up until then had been that bars in the city could easily be categorized by the type of customer they appealed to, and that certainly had been the way they had been described and regarded by Bob Manahan and the other people I'd first met in '59. However, in Glennon's there was no discernable physical type, no predominant style of dress, and a somewhat wider age range than I'd noticed before -- and, as I found out, a far greater mix of classes/occupations. And that brittle tone of campy bitchiness was missing. I liked the difference right away.

(My guess is that had I had the opportunity to go to more bars more often in '59 that I would have found that variations of the Ivy League uniform or the alternative "faggy" clothes from the likes of the Village Squire were not the entire gamut of gay male dress either. I'm guessing from a couple of quick trips into the Tic-Toc, Annex and Big Dollar in '59, that jeans, tee shirts and a range of sport shirts were a regular part of the scene there - as well as in the hustler bars. And even flannel shirts. Gasp! Proto-clones maybe.)

Over the following years many of the bars which opened

were like Glennon’s in terms of clientele. I suppose this was pretty much

dictated by the fact that the heat was on so intensely that there were few bars

to go to; therefore, everyone pretty much had to go to the same places. I've

often thought in retrospect that this prolonged anti-gay bar campaign may have

helped to break down some of the affectation and bitchiness that was

part of the gay New York I was first introduced to. However, despite what seemed to

me to be a wider variety of guys, there might be only one or two black guys in a

bar, and a few Hispanics. (My judgment of who might be Hispanic was off

during my early years in the city. I had grown up in a town whose white

population contained a large Sicilian minority, many of whom could have easily

been taken for Hispanics. And it was really two or three years before I

was aware that many of the people that I saw as Italian or Sicilian were

actually Hispanics.)

I went to Glennon's far more often as the 14th Street

Cafe spooked me because quite a few of the guys wore leather jackets, caps and

boots, and not being nearly as crowded as Glennon's the atmosphere felt too intense for

me. On the other hand, I remember that I did go home with guys from there on

two occasions. One them, Tony Montez, was a well-built, swarthy guy of

Mexican-Italian background, who talked out of the side of his mouth like a movie

gangster. He had an apartment in a tenement in a still Italian section of the

south Village, a neighborhood I'd never been in. While we never became close

friends, Tony was someone I'd hang out with if I saw him in the bars or at the

beach. Oh, he was also an "older" guy, thirty-five, maybe a bit

older.

I went to Glennon's far more often as the 14th Street

Cafe spooked me because quite a few of the guys wore leather jackets, caps and

boots, and not being nearly as crowded as Glennon's the atmosphere felt too intense for

me. On the other hand, I remember that I did go home with guys from there on

two occasions. One them, Tony Montez, was a well-built, swarthy guy of

Mexican-Italian background, who talked out of the side of his mouth like a movie

gangster. He had an apartment in a tenement in a still Italian section of the

south Village, a neighborhood I'd never been in. While we never became close

friends, Tony was someone I'd hang out with if I saw him in the bars or at the

beach. Oh, he was also an "older" guy, thirty-five, maybe a bit

older.

The 14th Street Cafe was the first place I was ever in that could have been called a leather bar. Judging from the fact that a fair number of the guys, as I recall, were fitted out with boots, wide belts, jackets and caps of leather, and that they seemed to be familiar with each other, I would guess there had to have been other bars like this one before that I simply hadn't heard about. Quite likely, as the people I had met in '59 would definitely not have been interested. (The Big Dollar, based on one brief visit, would have been a likely candidate.) About 1963 a bar opened in the West Twenties or maybe it was the Thirties, called the Exchange - from its proximity to a major telephone building - and it certainly attracted a leather crowd.

These were the years when you might come upon your most recent "favorite" bar (out of 2 or 3 open) and find a large sign in the window saying RAIDED PREMISES BY ORDER OF THE NEW YORK CITY POLICE DEPARTMENT. What to do? At one time the answer would have been to go somewhere else, but when there only were one or maybe two others, and they were not necessarily anywhere nearby it wasn't that simple any more -- particularly if you were literally counting your nickels and dimes like I was then. I can remember the first time I screwed up my courage to go in anyway, but that was because I saw a few other customers through the window. It was about this same time, and was a place around Sixth Ave. and 57th St. A bored cop sat inside and there were a dozen or so customers. There was a lot of forced humor and not much fun, and early home or to one of the meat racks to cruise. In a few days or maybe weeks (if they were luckier) that bar would be padlocked and that was the end of it. Then you would hear of another one.

GETTING TO KNOW YOU

As much as my work schedule interfered with a normal social life, the kid-in-a-candy-store mentality of a young male in New York certainly contributed to making some contacts one-off tricks too. If I didn’t meet anyone from the scads of incognito movie stars and celebrities the college clique had told me populated the gay subculture, I did learn in a latter-day expression that “we are everywhere.” I can recall being a bit surprised by this, which maybe is an indication that I had accepted the stereotype that gay men were mainly to be found only in certain occupations, i.e. – hairdresser, interior decorator, dancer and so on.

Deke was a young English exec, who passed through the city several times on his way between the UK and Brazil. Eddie was a free-lance accountant, who introduced me to the film and soundtrack of Black Orpheus – and, thus, to Brazilian music, which eventually became a passion of mine. Bill, was a Greyhound Bus dispatcher, Stan a fireman and Paul a policeman – who picked me up on Central Park West as he was going home after his tour of duty. Sid, a cute man - in his late 30´s it turned out (gasp!) - was a merchant seaman; a Mohawk-white mixed blooded guy, George, was an airline steward (no flight attendants then) from Canada. The incredibly built, Merle, designed sets for television and the theatre, and was a kind of 60’s NYC gay muscle celebrity - and as I found out later when I went to Fire Island, he was king-of-the-roost in a house bodybuilder roommates in Cherry Grove, and guys would make up a reason to take the walk their house was on to see if they were exercising out on the deck.

I met a couple of guys who were very nice and had their own odd schedules which dovetailed with mine, and I saw each of them for awhile.

Bob

Glock lived in the

village

in a very old one and quirkily laid out

building, on Cornelia Street. It was tiniest studio apartment I have ever

seen.

After getting off at the Times early in the morning, I

would take the subway downtown, get a couple of greasy burgers with onions and

two Cokes at Riker's on Sheridan Square and then go over to his place.

He’d put on some Billy Holiday LP’s and we'd have sex. His place was so small we had to sit on

the bed and use the window sill for a table while we ate our post-screw burgers.

The garret-like room, with a candle burning on the dresser, and old fashion

casement windows overlooking a paved courtyard made me feel like I was in Paris

not New York. Whenever I hear Billy Holiday singing

If the Moon Turns Green, I think of Bob, so perhaps it was a favorite of his.

Bob

Glock lived in the

village

in a very old one and quirkily laid out

building, on Cornelia Street. It was tiniest studio apartment I have ever

seen.

After getting off at the Times early in the morning, I

would take the subway downtown, get a couple of greasy burgers with onions and

two Cokes at Riker's on Sheridan Square and then go over to his place.

He’d put on some Billy Holiday LP’s and we'd have sex. His place was so small we had to sit on

the bed and use the window sill for a table while we ate our post-screw burgers.

The garret-like room, with a candle burning on the dresser, and old fashion

casement windows overlooking a paved courtyard made me feel like I was in Paris

not New York. Whenever I hear Billy Holiday singing

If the Moon Turns Green, I think of Bob, so perhaps it was a favorite of his.

He and I went to see A Death in the Family. (While the ticket was a bit of a stretch for me, theatre was still affordable for most people in these years. Broadway was thriving, new dramas and musicals as well as established hits were abundant.) Once he came up to my apartment and played Blue Prelude (or was it Prelude in Blue) on Milton's piano. Ten years later on a Sunday afternoon, Santo, a guy we knew from the local bar took a gang of us on a tour of downtown gay bars in his Caddy convertible. We hit some spots around West & Christopher, one was Peter Rabbits - right around tea dance, the music was top-notch and there were two or three drag queens who were a lot of fun. Last stop on the way uptown was the Eagle. Bob was a bartender, or at least working there. He was slightly huskier, but otherwise looked much the same, and he still had his beautiful head of soft blond hair that looked like a mane of silk thread.

A little later, or perhaps even a year or two later, I met Eddie LeMans. On first take he was rather odd looking, a slender fellow with a head that was quite definitely too large for his frame. The fact that he had lost most of his thin blond hair from the front of his head further accentuated his bulging forehead. However, any impression of unattractiveness vanished when he smiled. Eddie hardly ever just plain ol’ smiled. His usual smile was a beaming grin, and matched with his big, pale blue eyes, which always looked a bit lost in dreamy melancholy, meant that he was as irresistible as a puppy. And he was a gentle guy, seemingly without a mean bent in his disposition.

He played the trumpet for

a living. It was a rather catch-as-catch-can existence, as I recall, though he

did play a loose circuit of bars and clubs with varying combinations of other

musicians. I never saw him on a gig, but I did hear him play anyway.

Eddie lived in a walkup apartment on Sullivan Street. You entered a large kitchen, where the fixtures were bunched into one corner to make room for the bathtub, and there was an old table and two wooden chairs. A window opened onto a large air shaft or perhaps it was an alley. In the front, street-facing, room there was a mattress on the floor.

Sullivan Street

That summer it was hot and

steamy as a crotch. I’d wake up in the morning soaking wet, the air already

yellowish-grey with humidity and pollution, and Eddie would have left a tired

old electric fan aimed so it was blowing hopelessly across the mattress. Each

morning, for the first few moments, I was immediately miserable, and primed to

be pissed at the world; then I would hear Eddie playing very softly in kitchen,

and I’d lie there and listen.

That summer it was hot and

steamy as a crotch. I’d wake up in the morning soaking wet, the air already

yellowish-grey with humidity and pollution, and Eddie would have left a tired

old electric fan aimed so it was blowing hopelessly across the mattress. Each

morning, for the first few moments, I was immediately miserable, and primed to

be pissed at the world; then I would hear Eddie playing very softly in kitchen,

and I’d lie there and listen.

(right) 1963 smog pollution - not retouched. (AP photo)

How good a trumpet player he was, I don’t know. The names of the clubs he played in meant nothing to me, but perhaps they were not totally insignificant in the world of jazz aficionados. His playing was light and clear, always just a bit sad – I thought – and a little “sweet” too, or sentimental, maybe. He liked Chet Baker’s playing, could be it influenced his own. A long time latter I got interested in jazz and picked up on Baker myself; so much time had passed it seemed just like Eddie again to me.

When I got up and went out in the kitchen, Eddie would be sitting at the window in his undershorts, usually playing with a mute on his trumpet. He would make coffee, always instant, always awful. We’d take the cover off the tub and have a bath together. It was sweet and romantic, but it was almost a necessity. The water pressure was so terribly low that it took forever to fill the tub a few inches, but with two of us in it the water rose to a level that promised the possibility of a real bath.

Seemed like when we left the building everyone on the street knew Eddie and said hello, and the neighbors evidently didn’t mind his playing. One beastly hot morning a woman was sitting on a folding chair in front of the building next door, sweating and fanning herself with the Daily News. As we passed she said something like, “That was nice today, Eddie. Real pretty.”

After I left Eddie in the morning I'd hang around the Village and browse in a branch of the Marboro chain of book stores on Eighth St., or in the Eighth Street Bookshop on the corner of MacDougal, where I saw Allen Ginsberg once. (The latter place was a regular shopping magnet for many literary celebrities of the day, though I wouldn't have recognized most of them.) The Village Squire, the "faggy" clothing store that had advertised on the back pages of Esquire (and whose catalog mailing list I joined in college, mainly for the drawings) was still on the north side of the block, though the string of gay bars - the Old Colony, Main Street and Mary's- was closed. Then I'd catch the IND 8th Ave. uptown at 8th St. and Sixth Avenue, which was - like Sheridan Square further west - a Village crossroads. The Women's House of Detention was on one corner (where a garden is now), the churchy-looking Jefferson Market was next to it, and around behind them the old Village "plague alleys," Patchin Pl. and Milligan Pl. Across from the prison was Sutter's bakery (my introduction to the French cruller) with the Village Voice offices above it.

One other encounter was surprising. I was at Glennon's bar and as I was

leaving around closing time, a stranger handed me a card and said something

like, "Stop by." It was for a place called the "Coat of Arms" with an

address on upper Broadway somewhere, and it was open after bar hours. As far as

I can recall, this was the first illegal after-hours place that I'd heard of.

When I got back uptown to my apartment I looked at the card again and realized

that it was very close by. I walked down Broadway, checking the numbers,

and was surprised to find that the address

was the grand old Ansonia apartment

building! This made me a bit nervous. (What I didn't know then was

that the Ansonia was far less classy than it's appearance suggested.) The

lobby was empty and I went up to the floor indicated and found the door - the

same card was thumb-tacked next to the buzzer. I paid a small fee to get

in. The bar was the kitchen counter. There was a bed room in the

back, which was being used for sex I saw when I went to the bathroom later, and

a handful of guys were sitting around in the living room.

was the grand old Ansonia apartment

building! This made me a bit nervous. (What I didn't know then was

that the Ansonia was far less classy than it's appearance suggested.) The

lobby was empty and I went up to the floor indicated and found the door - the

same card was thumb-tacked next to the buzzer. I paid a small fee to get

in. The bar was the kitchen counter. There was a bed room in the

back, which was being used for sex I saw when I went to the bathroom later, and

a handful of guys were sitting around in the living room.

The Ansonia Apartments

One of them was someone I'd gone to school with! Ted had left not long after he reached the legal age of sixteen, and I had never seen him since. That was five or six years ago, but he looked pretty much the same. He was a mixture of white and Native American, with a slightly ruddy complexion and reddish blond hair. He still had a hard, muscular body, which people said came from the fact that his father was a mean bastard who beat his kids and worked them like they were animals on their farm. Ted had been a terrible student, and very much of a brooding loner that most kids walked around. It was obvious in gym class that he was immensely strong, and if he was antagonized he was a maniacally ferocious fighter, so even the biggest bullies stayed clear of him. I discovered one day while we were standing around in the dark watching a movie in shop class that the kid who had first seduced me was up to something. I reached over and discovered that he had unbuttoned Ted's fly, and was playing with Ted's rock hard dick.

It was five or six years since we'd last seen each other in our little hometown, and we were both surprised - and the other guys were curious. He was friendly enough for Ted, though clearly ill at ease, but neither was I as the guys sitting around didn't disguise the fact they were listening. I called him a couple of times at the fleabag hotel in our neighborhood where he'd told me he was staying. But he clearly had zero interest in meeting again. I wasn't yet very savvy about anything that wasn't pretty much white bread gay life. But after I thought about the evening, a few things sunk in. The two guys who were running this "club" were both wearing a little leather, and I'd noticed a couple of leather jackets slung on the backs of chairs. The guy who'd handed me the card in Glennon's could have come over from the 14th Street Cafe, which got a leather clientele. Ned's interaction with one of the guys who lived in the apartment, I'd noticed at the time, had been peculiarly subservient for someone with Ned's temperament. Maybe he'd found a kind of ritual replacement for his father in a leather crowd.

I never ran into Ted again.

Probably the most important guy I met was Arthur, a Jewish guy who worked in his family's business in the garment district - "the most important" because it was through Arthur that I began to have a circle of friends and a regular social life. Arthur and I met and tricked one time, but we hit it off as friends. He lived on West End Avenue, in a better part of the neighborhood. He took to calling me whenever his friends were coming over or going out as a group, and it was a contact that lasted even though I wasn't working normal hours yet. Arthur was a native New Yorker, and his circle of friends - with the exception of his best friend, Greg Stone - were Jewish, and born and raised in the city or its suburbs. Listening to them talk about growing up and their family life was an intensive course in Jewish New York. New York City had the second largest Jewish population of any city in the world, and though it had at one time been considered an "Irish city" (even when the Italians had come to form a large part of its Catholic population), this had been changing for decades and was to climax in the late Sixties. Much of what was pervasively and distinctly New York in the way of food, slang, humor and spirit was derived from the Jewish - and more specifically perhaps, Yiddish -- background of people like the grandparents and parents of Arthur and his friends. And the slang and humor found a place in the gay subculture of the city.

THE TIMES AND TIMES SQUARE

While the copy boy/clerk job consisted of nothing more demanding nor interesting than running pieces of copy to the various news desks, with occasional jaunts to other parts of the building or outside, I didn’t find it boring at all. We were usually very busy, and the surroundings and the people were interesting. My peers were almost all grad students at the Columbia journalism school or recent college grads. They were a brainy, friendly bunch of guys, most of whom always brought a book to work. There was a lot of discussion about what guys were reading, and I’m sure this pushed me to fill in the many gaps in my education. I plunged into French literature with André Gide, Anatole France and François Mauriac - and the latter suggested a long detour through Graham Greene – usually reading three or more books by each author before moving on.

(right)

Times Square IRT station mosaic sign

(right)

Times Square IRT station mosaic sign

I came to work late in the afternoon or early in the evening, and I usually ate something at one of the cafeterias or cheapo hamburger stands on or near 42nd St. My earliest daytime impressions of the area were simply that it was terribly grubby and obviously a center for sleazy businesses. However, my lunch hour was late at night when the area was thronged. Also, one of our jobs was to pick up the latest edition of the other New York papers (there were seven back then), plus the Wall Street Journal, the Sporting News, and other specialty publications. First stop was a newsstand on the corner of Seventh and Forty-First in front of a theatre that showed “girlie movies,” then around the corner and downstairs to one in the Times Square station of the IRT subway – and that place looked liked Hell’s waiting room after sundown! These night time trips outside introduced me to a Times Square/42nd St. that was garishly lit, noisy and even dirtier than in the daytime, and thronged with people leaning against the store fronts, hanging out around the all-night movie houses or sauntering up and down as if it were the Fifth Avenue Easter Parade.

Times

Square dining, 2 for 25 cents burgers and franks (photo: Klaus Lehnartz)

Times

Square dining, 2 for 25 cents burgers and franks (photo: Klaus Lehnartz)

To get off the street on my late night lunch hours I often went into some of the many stores that sold back-dated magazines, old paperbacks and racks of mostly grade Z current paperbacks. The array and amount of old magazines was fascinating, and there were always many beefcake mags going back to the early Fifties to entertain me – if another copy boy wasn’t with me. One night, having forgotten to bring a book to work, I was doubtfully browsing and lingered over a paperback with only a mildly erotic cover. After skimming, I decided that it was probably going to be the best of a not terrific selection, and I would take a break from culture. The author had a Japanese name. While I had taken a very short survey course at Syracuse on Japanese culture and history, I’d never read any Japanese literature. I read the book at work and enthused over it as one of the greatest things I had ever read. No one had ever heard of it, no one would read it because of the silly cover, etc. Eight years later the author won the Nobel Prize for literature. He was Yasunari Kawabata and the book was Snow Country. (Unfortunately I had not kept in touch with any of these guys, and was not able to thumb my nose and say, nyah-nyah!) I went back to the same store and after a lot of searching came across another paperback by a different Japanese author, Some Prefer Nettles by Junichiro Tanizaki. These finds were the beginning of a fascination with Japanese culture (especially literature) that was to be a major interest for the rest of my life. Another find in the same store was a copy of Gide’s Corydon, his apologia for homosexuality. The title only caught my eye because the work had been very gingerly referred to in the prefaces and introductions to his novels that I’d just recently read, so the odd word had stuck in my mind.

So, in at least two cases even sleazy Times Square made a high-brow contribution to my remedial education.

Once

in awhile it would be my job to “clean the spike” in the Times newsroom.

This was a long spindle on which the PR releases, newsletters, etc. that came

into the paper ended up. One night I came across a release from the Alcoholic

Beverage Control Board naming bars that had been closed for legal violations.

This became my printed introduction to myself as I was perceived by the law.

Glancing down the list, I came across a place that had been closed for

“congregating homosexuals,” and it went on to indicate that their activities

were “immoral” and “undesirable.” In some strange way this was more repellant

and intimidating than the presence of a policeman sitting in a raided bar. This was the