Wonderful Town (pt. II) 1962-66 The Gay Sixties 1966-70 The Juicy Life 1971-76

Juicy Life (pt. II) 1976-80 Losing Alexandria 1981-87 The AIDS Spectacle

Losing Alexandria (pt. II) 1987-1990's

When My World Was Young 1945-56 The Yellow Brick Road 1956-60 What a Wonderful Town 1960-61

Wonderful Town (pt. II) 1962-66 The Gay Sixties 1966-70

The Juicy Life 1971-76

Juicy Life (pt. II) 1976-80

Losing Alexandria 1981-87

The AIDS Spectacle

Losing Alexandria (pt. II) 1987-1990's

the JUICY LIFE

1970 - 1974

Lush Life is a classic torch song which has been recorded by many jazz vocalists. It was written in 1938 by Billy Strayhorn and offered to bandleader Duke Ellington; a year later the openly gay Strayhorn had become his arranger and composer-in-residence. Ellington called Strayhorn, "my listener, my most dependable appraiser [and] critic." Lush Life is a sardonic lament for a life of luxury, sex and parties.

Billy Strayhorn

Billy Strayhorn

It was rather odd that this old song was recorded by Donna Summer of all people in the early 80s done in a fairly straightforward fashion and plunked down in the middle of the disco diva's new album.

Or was it so odd?

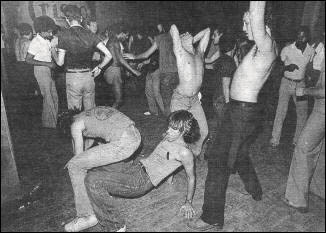

Strayhorn's wry label "lush life" may have been appropriate to his time, but in the 70's some gay men created a lifestyle that was beyond lush. The era when gay men ornamented their subculture with borrowings and fantasies from the world of entertainment and cafι society, and circled elite cultural and social circles like bees around flowers was falling into twilight. There was another gay style in the making, and it was a melange of the "sexual revolution," drug culture, Hippies, black music and urban attitude, Tom of Finland...add sex to taste and stir. Ironically, after this lifestyle had evolved, straights would come to it as voyeurs and hangers on, and they became the borrowers, circling around a world of gay discos, parties and resorts.

It had a quality of over-ripeness. It was the Juicy Life

For the few it ultimately became the life where more wasn't better...it was never enough.

John Tristram

That only a relatively small number of men, in a few urban areas, were totally wrapped up in living this way to the max is not the point. This lifestyle was to become in the minds of many gay men, and some straight people as well for better, and often for worse the signature of gay life.

As knowledge of the Stonewall raid and Gay Pride parade spread across the U.S. and the rest of the world the public commemorations it inspired became, as much as anything, pageants of this new urban gay lifestyle. While the events of June '69 were often known in only the vaguest way even among many New Yorkers the word "Stonewall" took on the significance of an invitation to celebrate living an openly gay life. In the city the first years of what became an annual parade saw plenty of political placards, raised fists, chanting, etc. in the Sixties style, but rather quickly especially after the marches reversed direction and ended in the Village rather than uptown a tone of joyful physicality and exuberance was predominate.

I think it would have been around 1969 that Ken brought back some copies of the Advocate from a business trip to the West Coast. And as slick gay publications began to proliferate and become available across the country what was being publicized was the way of life in places like New York and San Francisco.

THE FIRST DISCO?

In an era that encouraged eroticism and public display, combined with a new and increasing tolerance for gays e.g. liberalized laws allowing same sex dancing gay men found and eventually helped shape one stream of American pop music as an expression of their liberation. While the juke boxes in gay bars were barometers reflecting changes in gay taste, and its increasing divergence from that of mainstream white audiences, it was the dance bars, of course, which underscored that this music was for the body, not just the ears. Despite latter day vilification of bars and clubs of this era as "racist," my own personal observation was that blacks and Hispanics were a presence there, whereas they were much more rarely so in straight places. And I believe this was one of the pipelines for gay venues into the music of non-white night life. In time the dance places were providing such an overload of feedback that it killed the juke box in most gay bars in the city.

Arthur, run by Sybil Burton, ex-wife of actor Richard, opened in New York, and it was the first discotheque with a format similar to what later became standard. A "discaire" (DJ) played a thought-out mix of tunes, building a momentum that packed the floor for the climax number of the set. But it was a style that didn't really catch on with straights well perhaps because straights leaned so heavily into Rock and the discotheque idea kind of staggered along with them. And as far as gay dance places were concerned, the illegal nature of them made a juke box loaded with fifty or hundred discs a cheaper investment and one the customers kept pumping money into if they wanted to dance. Still, the pot was on the fire.

The

prototype for the American-style disco was a place called The Sanctuary. It was

opened in 1969 before the disco era, as such, got underway. Too bad, because the

place was instantly recognizable as a new ultra-hot idea as soon as you entered

the main room. If you've ever seen the movie Klute, there is a scene

where the prostitute, Jane Fonda, is in a dance club

very brief. It was

filmed in The Sanctuary.

The

prototype for the American-style disco was a place called The Sanctuary. It was

opened in 1969 before the disco era, as such, got underway. Too bad, because the

place was instantly recognizable as a new ultra-hot idea as soon as you entered

the main room. If you've ever seen the movie Klute, there is a scene

where the prostitute, Jane Fonda, is in a dance club

very brief. It was

filmed in The Sanctuary.

(right) The Sanctuary

Unfortunately, they cut all the scenes which show how huge the place was and it's rather unusual decor and customers. It had once been a large Baptist church and its interior was kept fairly intact. The huge pipe organ still filled the front of the church. The pews had been ripped out to make a dance floor where the congregation used to sit, and had been reinstalled in tiers running parallel to the length of the dance floor. Over the arch at the rear of the church a huge mural had been painted which showed the Devil fondling a naked woman sitting on his lap and some Priapic goats or whatever on either side of them. Under the arch was a bar and in front of it a small palm court with tables at the edge of the dance floor this was top drawer seating area. The entire space was lit with chaser lights and flashers, and strobes were used. The place knocked me out! And the first night Ken and I went there remains a contender on my "most unforgettable" list.

It had started out as a straight club called The Church, but even though it was a former Baptist church, the Catholic archdiocese complained that its transformation was a blasphemy and managed to get a judge to issue an injunction to close it. However, it was soon open again as The Sanctuary but with a gay clientele now. The first time Ken and I went, I remember the crowd was more straight than gay, so possibly that was when it was still The Church. (Or perhaps these people were an overlap right after the change.) Next time, however, it was mixed very unusual for the times, but the straights seemed totally cool about it. A bit later I recognized a couple of the guys manning the door as familiar faces from the old gay bar era downtown, and now the clientele was exclusively gay.

The Sanctuary did not last all that long until early1972, I

think. But it had nothing to do with having

gay people there. There was dope being sold

(and

used) on the premises - heroin, I heard, and that contributed to whatever other

illegalities were kept under wraps. The

transvestites stayed around the bar area dressed in evening gowns and were

constantly flying between there and the head to touch up their makeup and their

drugs. One night I walked in the men's room and a

couple of really spaced out drags were at the sinks, and one of then had a

syringe dumped out of her evening bag onto the counter along with her other

stuff. The place kind of fell apart, sometimes guys were getting it on in

the johns, and then, I heard, in the hallways of nearby buildings too.

From the viewpoint of a 70's/80's disco aficionado, the place was better than the music. However, this was before the 12-inch single and instrumental B side tracks, and well before disco music as such.

Francis Grasso

Except

there was Francis Grasso, a genius who could put together a

bunch of those fucking little 45 rpm's or LP cuts just like he knew he was

inventing the scene and the sound the magic of what would become the Paradise Garage and

The Saint years later. He is usually credited as being the first club DJ to

perfect slip-cueing a record and releasing it on beat while creating a

continuous set of music, segueing one song into another to create a flowing

stream of gathering energy. This guy was working with the audio equivalent of

Stone

Age tools, and he was surely something on the order of a shaman. He

was also straight.

The Sanctuary packed in the crowds. And Grasso had us flyin' on a mix of Aretha Franklin, James Brown, Gladys Knight & the Pips, Booker T. & the MG's, laced with rock 'n' roll and ethno tracks,

Mitch Ryder, "the gargantuan volcano"

Chicago Transit Authority, Santana, the relentless Mitch Ryder & the Detroit Wheels, Olitunji and the Drums of Passion....a smokin' version of Bob Dylan's I'll Be Your Baby Tonight by a gospel choir called The Brothers & Sisters, and a favorite of mine Little Sister's hypnotic "You're the One." I have to say it again, Francis Grasso was magnificent!

Same-sex dancing was legal now, and it looked like this was the direction gay night life was headed in.

Cherry Grove has also laid claim to being the birthplace of the American disco ambience. In 1969 a guy named Ted Drach leased the Cherry Grove Hotel, a large U-shaped, two-story clapboard structure, from Jimmy Merry. Jimmy had put in a pool sometime in the 60's and there was a modest-sized dance floor in the bar, plus a large adjoining dining room. Drach had no previous experience supposedly just money to lease the hotel, and the Sea Shack (Merry's small restaurant built on the dunes, overlooking the beach.) According to what is recounted in Esther Newton's history of Cherry Grove, Drach claimed that early in the summer of 1970 he was followed home one night by a guy and they tricked. The guy claimed to be an electronic genius. Drach was looking to revive the hotel as the main center of social life in the Grove. Free-style dancing, as opposed to partnered dancing and line dancing, was already popular in the city. Shazam! The anonymous genius trick took over the larger dining room area, covered everything in blinking Xmas lights as well as lights that pulsed to the music, installed speakers to kill with and a DJ booth: The American disco is born.

This may well have been nothing more than a tall story that was put over on Newton one with more than a little spite and malice in it as many people clearly recall Michael Fesco being the driving force behind the birth of the Ice Palace, as the place was called. And he was the manager there for four or five years. Gay men started walking down the beach from the neighboring Pines to dance, and that prompted the restaurant owners there to take notice. Later in the decade Michael Fesco created Flamingo in Manhattan, undoubtedly the premier club while it was open. The music at the Ice Palace was not yet disco per se, of course, but mainly up-tempo soul. However, the scene was set and it would all come together in time. Sort of like the stable waiting for Baby Jesus.

John Whyte's Blue Whale bar and restaurant was the center of Pines social life right at the end of the Sixties decade, and it had a popular "tea dance" with another dance session post-dinner. In 1970 the neighboring Sandpiper restaurant was shooing the dinner crowd out around 10 or 11 p.m. so the tables could be shoved out of the way and a dancing crowd take over. The Blue Whale became the Boatel, which still had its jam-packed Tea, but the evening action belonged to the Sandpiper. I went out there once in '73 with Ken and his new boyfriend and a couple of straight girls right after he'd sold out his interest in a PR partnership. The Sandpiper was packed, and sweltering there was no a/c, just the open windows. I don't remember whether the DJ was using tapes or putting 45's together (no 12" singles existed at this time,) and the only music I remember for sure is an Aretha Franklin song that the crowd was wild for.

Although the Grove's gay residents (which was almost all 300 houses with their several thousand summer residents) were pissed, Drach in order to stay on top of the Pines' competition financially began to advertise his place in the city, and in the neighboring straight communities on Fire Island. This brought in a huge influx of business for him, but almost swamped the community in many ways. I would imagine, however, that his move probably had the effect of introducing this concept of a dance environment to more straight people.

PICADILLY PUB: THE BEGINNING

In the beginning God may have said, "Let there be light," but on what was to be the new gay Upper West Side, it was Jenny Tobin who said, "Let there be the Picadilly Pub." (And, yes, it only had one "c.")

The neighborhood got a calculated taste of

a new style in

gay life when this bar opened in 1971 in a former laundromat, on the other side

of the avenue just a half a block

up Amsterdam from the Candlelight (which by now, I think, had dropped "Lounge"

from its name.) There was nothing special about the appearance of

the bar, the floor was still paved with its old fashion white eight-sided tiles

and the walls were simply rough plastered. A long bar had been installed along

the left-hand wall, where the machines had been, there were a few small,

out-of-place sconce type lighting fixtures with cutsie little shades and a

narrow shelf for customers to put their bottles on along all the available wall space.

(right) Picadilly Pub was beneath red flag & building on other corner is the rear of the Beacon Theater

The manager was a new face in the neighborhood, a young Puerto Rican, Nefty, with a dazzling smile, but all the charm of a rusty razor. He had very definite ideas about two things that were going to make the Picadilly a success: the music and the bartender's image. The Candlelight was an old bar which was gradually changing with the times; the Picadilly was a "new" bar not just in the sense that it had recently opened, but more importantly it was a new kind of place in the neighborhood.

I was living alone in a studio apartment on West 80th St. now, and this place became almost the only gay bar I went to...I loved it.

The juke box was a shrine to soul Marvin Gaye, the O'Jays, Gladys Knight and the Pips, etc., and funk - Kool and the Gang, ConFunkShun.... White artists were limited to up-tempo hits that could fit in with this basic sound, from the likes of Elton John (e.g. - Take Me to the Pilot) and Rare Earth. Judy Garland had one record on the box in the beginning, as I recall, and there were one or two by the R&B-toned Dinah Washington. However, over the next few years black singers like Lana Lee, Millie Jackson and the raw and mean, Yvonne Fair showed up Judy's record went to juke box limbo, the lower right hand corner of the selection menu, and then disappeared. (Barbara Streisand took her place, but with a different up-tempo type of music, of course.) The entire roster of great black groups and soloists was on the menu, plus music from the blaxploitation films of the era, Superfly and Shaft. The juke box was carefully managed: recordings showed up as soon as they were hot or sometimes just before and last season's favorites were eased off at a steady rate to make room for new music.

This was music that demanded bodily motion, and aside from the individual pleasure this brings, I have to think that Nefty understood on some level that it also created a kind of group experience in the bar. Unlike the assumed intentions that brought the customers together the desire to socialize, the hunt for sex, the music and the heightened volume at which it was played (compared to bars in the recent past) virtually compelled a physical reaction. And each person could literally see himself joined with the others who were (physically) moving with the spirit of the place it was almost a dance bar without dancing. It worked, though at a much more subdued level, with an effect similar to the music in a "sanctified" church. The result was a much different and higher energy environment than the Upper West Side bar-goer had been used to.

Gladys Knight & the Pips, O'Jays (Back Stabbers), Millie Jackson (Back to the Shit), Marvin Gaye (Let's Get It On), Sly & the Family Stone (Dance to the Music), Yvonne Fair (The Bitch is Black)

Behind the bar were Nefty and Nathan, both in what would later be described as "clone" attire flannel shirts, veeery tight Levis 501's and boots or work shoes. And in the case of Nathan, showing a basket so large that one customer claimed it must be "a sock full of dirty laundry." Both of them, at least in the early days of the bar, had to lean so close into their customers to hear an order and made such intense eye contact that they became something of a joke. Nothing in this act was like the crew over at the Candlelight, where the bartenders looked like what they were just nice neighborhood guys who came in to work a job.

If the bartenders had a problem hearing the customers'

orders, the customers often had a problem hearing each other. There is a

temptation to say that the ability to "communicate" was inhibited by the volume

of the music and its constant rhythmic insistence. But, in fact, this wasn't the case at all: communication simply got guided into a very necessary intimacy. You were going to talk with your friends no matter what, even if

you had to talk right into their ears, so no

problem there. But meeting strangers and/or making contact with a

potential trick was actually being facilitated. The physical difficulty of

communicating easily in many parts of the bar

i.e. to just be fucking heard

meant

that the awkward social process of closing up the physical and psychological space

between you and the other guy had to be gotten over with almost

immediately.

If the bartenders had a problem hearing the customers'

orders, the customers often had a problem hearing each other. There is a

temptation to say that the ability to "communicate" was inhibited by the volume

of the music and its constant rhythmic insistence. But, in fact, this wasn't the case at all: communication simply got guided into a very necessary intimacy. You were going to talk with your friends no matter what, even if

you had to talk right into their ears, so no

problem there. But meeting strangers and/or making contact with a

potential trick was actually being facilitated. The physical difficulty of

communicating easily in many parts of the bar

i.e. to just be fucking heard

meant

that the awkward social process of closing up the physical and psychological space

between you and the other guy had to be gotten over with almost

immediately.

"The music's so fucking loud I can't hear you," said with a grin and a shake of your head, invited moving yourselves shoulder to shoulder and bringing your heads together - a business that could have taken half an hour to all evening in former bar environments.

And in the Picadilly the process of navigating from the front door over to the bar or down to the back of the room on a crowded night changed too. Instead of the awkward and pretty useless attempts to pass politely through a herd of guys with repeated "excuse me's" more appropriate to negotiating the aisle of a railway car full of commuters progress through the Picadilly was something on the order of traversing the length of a sexual sandwich, with a sometimes high incidence of harmless caresses and appreciative remarks along the way. But then the music was War's Slippin' Into Darkness or maybe the Staple Singers' I'll Take You There.

(Forget about getting a case of the vapors over being "molested" as would happen nowadays, if a guy didn't keep hands-off after you gently pushed it away a simple, "Fuck off" was the problem-solver.)

Soul and funk appealed to the feet and the pelvis, but there was an ironic something more. Their lyrics often had references to, and sometimes were very much about, discrimination and oppression of blacks by white America. And yet in the Picadilly (and other gay bars) this musical menu - with it's commentary on racial inequality - was being served up to a group of customers that was more white than black or Latino. I don't doubt that we white guys edited out bits and pieces of the lyrics that made us uncomfortable - similar to editing out the "she's" in old ballads - but much of the lyrical content was right on the dime as far as the situation of gay people was concerned. Of course you encountered anti-gay prejudice from blacks, e.g. in the Greek all-night coffee shop that had been next door to the Pic or in the Black Panthers' propaganda which equated gay men with "baby rapers". But the main force of homophobia that white gay people endured came from the white-dominated society, i.e. from other whites. It was whites who truly created and maintained the entire edifice of both legal and customary oppression of gay people. It was the white society which closed the doors to employment, education, public accommodation, housing, etc. to gay people. It was the power of the white man which brought discrimination against gay people into every sphere of life, it was the white man who set the law on gay people, it was the white man who created and promoted the humiliating stereotypes of gay people.

White gay men were not oblivious to these facts, and despite being white we enjoyed the barbs black music aimed at white power. What little room for resistance there had been for gay men in white culture had come from the role of comic sissy/fairy figures and to a lesser extent that of drag queen imitators of the man-destroying bitch; both of which at the end of the day confirmed straight stereotypes of the homosexual. I think gay men were drawn to black music and singers because we found in them what we would have liked to be but were not: until the 70's and 80's the rewards for passing, or even just masking our sexual orientation, were usually too great for many to risk the forthright bitterness, complaint and anger that blacks put out in their music.

Some gay people, usually those who were in their early twenties in this era, have memories of Glitter Rock - the New York Dolls, et al, but it was only something I read about, not something I listened to. And I don't recall my friends having any interest in the music, only in the outrageousness of that "scene" and it's gay associations (some a put-on.) As for rock in these years, much of it seemed fundamentally limp and irrelevant from a gay (or black) viewpoint, being rooted in the complaints of young straight, middle class whites. However, like most gay men I knew who bought records, I had a few favorite rock albums that stayed in my collection after most of my Sixties rock purchases had been dumped. At this point I remember four Beatles and Stones albums as being keepers - though I did hold onto a few others too; the Moody Blues and Pink Floyd were groups my friend Charlie and other guys had, and at the mid-point of the decade a new roommate was still very wrapped up in Emerson, Lake and Palmer. But youth-oriented Rock had cut off its roots in the original black rock 'n' roll, and in the early 70's was increasingly a white, male and macho thing.

Soul and funk was the gay menu of these year, and the Picadilly Pub got off to a roaring start because of it.

Rolling Stone reporter, Abe Peck, would write in

1976 that by the mid-Seventies "black style [was] more accessible to whites than

it was during the Smoldering Sixties." Indeed, but he is commenting

on the white mainstream playing

a belated game of catch-up to white gay men.

A SAFE GAY PUBLIC LIFE

The Mattachine Sip-in of 1966 probably had a more profound effect on the lives of gay men in NYC than any single event in the late Sixties. Gay bars were the principal meeting places for gay men not just for tricking, but for socializing. Their suppression by the Wagner administration in the first half of the Sixties decade had made meeting people and establishing friendships very difficult for new arrivals on the New York scene as I had found out. With the State Liquor Authority retreat after the Sip-in from its policy of prohibiting the serving of homosexuals, and the subsequent finding of the courts that this policy was not constitutional, the legalization of gay bars had occurred. Running a gay bar was no longer just a lucrative enterprise, it was a legal one. This did not mean that all the criminal interests disappeared from the field, but it did mean that they were now running in competition with anyone who could raise the cash and meet the licensing requirements...and steer clear of Mafia intimidation.

The gay population benefited in many ways most immediately in that the number of gay establishments serving alcohol began increasing rapidly. And as I recall, the managements and staffs were more consistently friendly, the surroundings were cleaner, the booze was unwatered and if the places smelled, it was usually from stale beer and not the stench of piss and shit from non-functioning plumbing. These changes were pleasant, the long term effects were potent.

Achieving public accommodation in a licensed bar was a major civil rights victory for gay people in the state. No longer was having a drink with your friends to risk public humiliation, harassment or arrest. After almost seven years of police action against gay life in the city, a sense of safety and with it the promise of an ongoing public social life came to the gay men and lesbians of New York.

The situation of gay people was further eased by the Knapp Commission investigation. In June 1970 Mayor Lindsay named a panel to began an investigation of corruption within police ranks as a result of spectacular revelations by a whistle-blowing patrolman (the famous Serpico) and a sergeant. The witness testimony before the Knapp Commission, as the panel was known, resulted in criminal indictments, and the commission's final report in December '72 found that corruption in the NYPD was widespread. No blockbuster surprises here for many gay New Yorkers. A new police commissioner and wide-scale reforms and disciplinary action reshaped the police force. This further ensured that gay bars and gay people would not be victimized by crooked cops.

While gay bars certainly functioned as places to pick up a trick, in many of them this was balanced by the steady patronage of customers for whom the bar was also a neighborhood meeting place. I met the overwhelming majority of my friends in gay bars, some on an individual basis and others because they were friends of people I had already met. And these were the people - and the places - that provided support which ran a gamut from pleasant companionship to help in time of serious problems. And my experience, I know, was shared by many others in the Seventies and Eighties.

The Lighthouse bar on Broadway in the 70's became the Westsider, an only briefly popular gay bar. Across Broadway on a side street the Bike Stop, a sharply decorated place, opened up. It stayed in business for many years, and had a loyal group of customers. It also got the reputation of being a haven for heavy drinkers and effeminate guys.

The Picadilly was reputed to be owned by the same couple, Sonny and Jenny, as the Candle rather strange, I thought at the time, to be in competition with yourself. In a year or two, Larry, one of their bartenders at the Candle became a bartender at the Pic, and in the mid-Seventies was the head bartender at the Westsider when it had a brief life but a rather good one as a gay cabaret called the Speakeasy. As it turned out, there was nothing "strange" about owning several gay bars in this part of the Upper West Side, rather an excellent sense of the neighborhood's prospects as it turned out. And once the gentrification process had clearly jumped 72nd Street, the rental and sale prices of properties in the West Seventies would rise at an ever-increasing rate, of course.

Wayland Flowers & Madame

Bob

Manahan, my Junior college year NYC summer affair, appeared one night in July

'71 in the Candlelight, with his old buddy, Jimmy, still at this side. He

and Jimmy were living together down on 56th Street now - in my old extended

unemployment flop, the House of

Flowers! For awhile he hung out in the neighborhood bars, and he may have

been the one who nicknamed them the "Pig Circuit," as a back-handed reference to

the old Bird Circuit - and a comment on their customers as well, I suppose.

Though Bob was as working class as could be, when it came to gay life he flung

caustic snobbery on the winds as if he were privy to a secret manual of gay

pedigrees

the equivalent of Burke's Peerage. In August he invited a few of us

down to their one-bedroom apartment in the House of Flowers. One of the guests

was another Upper West Sider, Wayland Flowers the puppeteer, who had brought along his famous character

creation, "Madame," and they put on an impromptu show.

Bob

Manahan, my Junior college year NYC summer affair, appeared one night in July

'71 in the Candlelight, with his old buddy, Jimmy, still at this side. He

and Jimmy were living together down on 56th Street now - in my old extended

unemployment flop, the House of

Flowers! For awhile he hung out in the neighborhood bars, and he may have

been the one who nicknamed them the "Pig Circuit," as a back-handed reference to

the old Bird Circuit - and a comment on their customers as well, I suppose.

Though Bob was as working class as could be, when it came to gay life he flung

caustic snobbery on the winds as if he were privy to a secret manual of gay

pedigrees

the equivalent of Burke's Peerage. In August he invited a few of us

down to their one-bedroom apartment in the House of Flowers. One of the guests

was another Upper West Sider, Wayland Flowers the puppeteer, who had brought along his famous character

creation, "Madame," and they put on an impromptu show.

Although Nefty disappeared from behind the bar of the Picadilly after awhile, the early replacements were cast in the original mold. One slender, sinewy guy got the nickname "Knife" because of his sinister sharp-featured face and deep-set eyes. But going on their third year the bartender image lightened up, and at one point Maggie Jiggs arrived on the scene. Maggie had been tending bar at the Stonewall the night of the famous raid in June '69, and was reputed to "have a following," i.e. was popular enough to attract customers from previous jobs. Well, forget it! None of the Pic's customers gave a shit about who Maggie Jiggs thought she used to be, and the pigeons must have eaten the trail of bread crumbs, because her "following" never appeared. Perhaps Maggie had expected the customers to roll out the red carpet, but whatever the problem was, he was sour-faced and sullen behind the bar. He was also notoriously light-fingered. When Larry was in the bar and Maggie rang up the cash register, Larry would often chant loudly, "One for Maggie, one for the bar. One for Maggie, one for the bar."

Maggie disappeared almost as fast as the proverbial snowball in Hell.

Both bars were beginning to change. When I stopped in at the Candlelight now I didn't recognize a lot of the crowd, and it also seemed that the Pic was getting a somewhat larger clientele of Hispanic guys, and a few more blacks as well. But, as in the Candlelight, the customers intermingled socially and sexually. There was, however, a small number of Hispanic guys who clustered at the end of the bar near the front door of the Pic, and I came to realize that some of them had a bit of difficulty speaking English. This was not something I'd ever noticed across the street. On the other hand, these same guys did talk and trick with non-Hispanic guys, so I think they probably hung together essentially so they could speak Spanish. However, there also continued to be white customers with blue collar or low-paying jobs in the crowd.

The mix of people did not change markedly until about '74 perhaps. While groups of friends met there the same way they had at the Candlelight, there was more cruising and picking up going on, probably due to the larger crowd and the influx of new guys into the neighborhood.

Socializing with the straight employees from my job at Fairfield Reading had been something of an eye-opener. While they were a mixture of white middle class, and to a lesser extent working class, college grads from around the country. As a group they were decidedly liberal to radical in their professed social and political views. However, I discovered that my straight fellow workers, despite living in Manhattan for the most part, had acquired no non-white or blue collar friends that I ever met, and the hangouts I went to with them appeared to be gathering places for white middle class young people. This was a very strong contrast to the occupational/social class/ethnic and racial mixture which I was experiencing in the gay life on the Upper West Side (and what I saw the Village, as well.) It would not be until later in the Seventies that I would work with any straight white people and find they had casual, unselfconscious friendships with blacks and Hispanics.

The

same year as the Picadilly opened, the Ike and Tina Turner Review did a sellout

concert of their standard raw, upbeat rhythm and blues music in a decaying old

Rococo movie palace, the Beacon Theater, on Broadway just around the corner

from the Candle and the Pic.

The

same year as the Picadilly opened, the Ike and Tina Turner Review did a sellout

concert of their standard raw, upbeat rhythm and blues music in a decaying old

Rococo movie palace, the Beacon Theater, on Broadway just around the corner

from the Candle and the Pic.

"We never, ever do nothin' nice and easy - we always do it nice and rough!"

Tina Turner was beyond terrific and in an era when stage show pyrotechnics were almost unheard of she disappeared at the finale in relentlessly pulsating strobe lights, an explosion and a puff of smoke! Later in the year they were to do a slightly slicker, but a much more sexually provocative version of this concert at Carnegie Hall. In 1969 a funky "swamp rock" band called Creedence Clearwater Revival had had a hit with a song called "Proud Mary." In 1971 Tina Turner did her version of it, and her extended maximum power songblast backed up by the vibrating, non-stop pelvis-pumping Ikettes became the Proud Mary if you were a gay man. The Ike and Tina Turner Revue was the soul and energy incarnate of the black juggernaut which totally ousted acid-, folk-, etc.- rock from the gay scene.

Also

in the neighborhood, in the basement of the venerable old Ansonia, were the

Continental Baths. While the "rooms" upstairs, cubicles would be more precise,

were the same old iron cot with paper thin mattress, the rest of the place was

more than a little splendid when compared to the grubby Everard or

the old Saint

Marks baths. Downstairs was a steam room and a sauna, of course, but also a

large pool, a dance floor, a lounge - and most famously a

cabaret, where the gay audience sat around wearing towels only. I went

there in the late 60's, and I

remember seeing Bette Midler and Barry Manilow which would have been 1970.

But I didn't go frequently, and I'm

not sure I went at all after '72. A bit later when had she become well known she delighted

talk show hosts by being very straight-forward about the fact that she

got her start at "the tubs." I saw, or at least glimpsed other

performers, but show time was not my reason for being there.

La Lupe

A 1973 issue of After Dark magazine has an ad for the Continental Baths in it listing previous performers who have appeared at the cabaret: Bette Midler, Barry Manilow, Labelle, Larry Kert, Freyda Payne, Vivian Blaine, Lillian Roth, Liz Torres, Peter Allen, LaLupe the wildly emotive Cuban singer, Eleanor Steber a former opera great who sang for a "black towel" event, and Dawn Hampton, who was approaching the peak of her cabaret career.

However, I stopped going to the Continental specifically because of the shows. They began to attract straights looking for a new trendy "kick," and for my money they and the shows got in the way of why I paid to go there. The whole show shtick dominated the place. I was not alone in my dissatisfaction, and the increasing annoyance that gay patrons felt reached a point where they abandoned the place wholesale and over a very short time span. It later became a club for straight swingers, Plato's Retreat.

The

music at the Pic was so good that it begged to be danced to or something. We

used to hang around the juke box at the back of the bar, and sometimes someone

would snap a popper and surreptitiously pass it among us. This was a no-no in

the bar. Even if the distinctive odor hadn't penetrated the smell of beer and

cigarette smoke, in fifteen seconds the fact that four or five guys were

standing around undulating to the music like they were at a Motown audition was a dead give-away. By and large we got away with it, but sometimes Larry the

bartender, who was a friend, would yell out, "Alright, tone it down back there!"

or with less good humor, "Knock it off, guys!" Over-the-counter sale of amyl

nitrite had been banned in 1969, but they were still available a

The

music at the Pic was so good that it begged to be danced to or something. We

used to hang around the juke box at the back of the bar, and sometimes someone

would snap a popper and surreptitiously pass it among us. This was a no-no in

the bar. Even if the distinctive odor hadn't penetrated the smell of beer and

cigarette smoke, in fifteen seconds the fact that four or five guys were

standing around undulating to the music like they were at a Motown audition was a dead give-away. By and large we got away with it, but sometimes Larry the

bartender, who was a friend, would yell out, "Alright, tone it down back there!"

or with less good humor, "Knock it off, guys!" Over-the-counter sale of amyl

nitrite had been banned in 1969, but they were still available a![]() s black market

items for a couple of years after. However, the government, as I understood,

then clamped down on their manufacture and distribution knowing

s black market

items for a couple of years after. However, the government, as I understood,

then clamped down on their manufacture and distribution knowing

full well that

they had been replaced for the most part in medical settings with tablets.

This may have been prompted in part by the fact that a few doctors would give

you a prescription for them for amyl nitrate vaporoles , or even sell to patients directly.

full well that

they had been replaced for the most part in medical settings with tablets.

This may have been prompted in part by the fact that a few doctors would give

you a prescription for them for amyl nitrate vaporoles , or even sell to patients directly.

A brand of head shop stuff. and a bottle of dealer's brew.

At this point the underground manufacture of poppers and their sale by dealers, began in earnest, and eventually the sale of a butyl nitrite substitute as brand name stuff in "head shops" and sex shops became common, with the bottles indicating that it was a room deodorant!!! or "head cleaner." However, the underground brew was usually far better. The upshot of this was that it became easier, and less smelly, to pass a bottle around than a crushed capsule.

Smoking grass in the Pic, or any bar, in the early Seventies would have gotten your ass lofted through the air and bonded to the sidewalk out front. But guys would go out and toke on a joint as they walked around the block it was late night in a quiet neighborhood, so the risk was slight. Before too much time had passed some guys simply stood in the doorway by the parking garage next door to smoke. But it certainly didn't please the Picadilly bartenders to have their customers blowing grass practically in its entrance.

The joint went around until the roach was too small to hold, even in a clip...then you opened the door and floated back into the bar, where the music of hits by Holland-Dozier-Holland and the other great black songwriters lifted you up and kept you up through the night Marvin Gaye - What's Goin' On, The Chi-Lites - Have You Seen Her and Oh Girl, Staple Singers - Respect Yourself and I'll Take You There, Laura Lee - Rip Off, Spinners - I'll Be Around, Betty Wright - Clean-Up Woman, Bill Withers - Lean On Me, Al Green - Let's Stay Together, Lamont Dozier - Take Off Your Makeup, O'Jays - Love Train, Gladys Knight and the Pips - Midnight Train to Georgia, Eddie Kendricks - Keep On Truckin', Earth, Wind & Fire - Mighty, Mighty...BT Express, Ohio Players, Three Degrees, Harold Melvin and the Blue Notes, War.....and even Barbara Streisand singing Jubilation.

By the late 60's and early 70's hallucinogenic drugs had became popular with many younger gay men, and a few guys in my crowd used acid every weekend it seemed. Various names floated around for types of LSD Sunshine, Purple Haze, "blotter"...etc. I still had an aversion to the idea of hallucinating, and didn't try it out.

POLITICS: YOU LOSE SOME AND YOU LOSE SOME

In the spring of 1971 the first gay rights bill was introduced into the New York City Council, but even though it had the backing of Mayor John Lindsay it failed to pass. It would fail to pass on the order of ten times over the next fourteen years. The strongest opposition was from Orthodox Jews and the RC Church, and it was city councilmen representing working class areas in the outer boroughs of the city who were its fiercest opponents in the council.

GLF folded shortly after GAA got underway. GAA, with its one-issue approach to gay rights and a formal structure, turned out to be a more stable organization. The group rented an old fire house in Spring 1971 from the City for a meeting place. It was located in SoHo, a district south of central Greenwich Village and north of Little Italy and Chinatown. (SoHo is a contraction for the phrase "south of Houston (street).) At this time SoHo was an area of grungy commercial buildings, with a thin population of residents, many Italian-Americans, and a trickling influx of artists. In the closing decades of the 20th century SoHo became the center of artistic life in NYC, and was filled with trendy restaurants and extravagantly expensive art galleries. Once cheap lofts were rehabilitated into residential living spaces selling for hundreds and hundreds of thousands of dollars, and in some cases millions. However, back in the 70's it was a quieter, somewhat rundown area and empty at night.

For

a few years GAA engaged in a barrage of publicity zaps, including sit-ins at

Harper's magazine and on the George Washington Bridge. After I moved to

West 80th I went with a friend to two or three general meetings of

GAA at the firehouse. This would have been in the winter of 1972 or early '73,

perhaps. I have only a few random recollections from these occasions.

One being that the

meetings were conducted (at least in part) by a guy dressed in leather from head

to toe, who - unfortunately - failed to deliver some no-shit mastery that was

sadly needed.

The meetings were interminable, the agendas grandiose, and

GAA seemed to have an endless, endless number of committees each populated by

pretty much the same names. The lesbians in attendance, I noticed,

spent most of the time chatting and were largely uninterested, except for

occasional

vociferously disruptive outbursts. Nothing I

heard or saw up close and personal moved me to join.

agendas grandiose, and

GAA seemed to have an endless, endless number of committees each populated by

pretty much the same names. The lesbians in attendance, I noticed,

spent most of the time chatting and were largely uninterested, except for

occasional

vociferously disruptive outbursts. Nothing I

heard or saw up close and personal moved me to join.

(right) GAA flag at the firehouse

GAA used to have weekend dances at the Firehouse and these were quite popular for awhile, the firehouse was a good space for this. Some guys from the neighborhood went down a few times. But it was an inconvenient place to get to by public transportation from the Upper West Side, and far easier to simply hop on the IRT at West 72nd Street and get off at Sheridan Square in the West Village.

While many guys went to the GAA dances, the organization had difficulty attracting people to join in its political activities. (Witness myself.) It remained a small group - less than 200, I have read - and eventually even its dances began losing out to the burgeoning West Village gay life. Then too, GAA made a miscalculation in its stance towards Mayor John Lindsay. Several times, both at official events and private social ones with his wife, they confronted and interrupted Lindsay in public. This did not sit well with many gay men. Lindsay was regarded very positively for having been the first public official in New York City to attempt to reverse the traditional homophobic policies of the city. Such a thing was nothing short of incredible for these years. He also backed the gay rights initiative in the City Council. The fact that "Handsome John" Lindsay also so clearly loved the city, and enjoyed going to Broadway shows, the opera and the philharmonic undoubtedly made him even more appealing to those gay men for whom these things were an important part of their lives too. And it seemed, as well, with the Reform Democrats having won the day, that gay people, especially in the Village where there was a very large concentration of them, would find a place in the regular political scene.

In the fall of 1974 the GAA Firehouse was destroyed by arson. Maybe its proximity to the heart of Little Italy was less safe than it had seemed, but the appeal of the GAA had already faded. Sixties style politics were almost defunct.

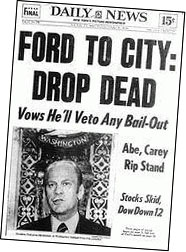

THE "RED MAYOR" BITES THE DUST

Mayor John Lindsay, nevertheless, was not doing well on the whole. His first term in '66 had begun immediately with a strike by subway workers during a cold January, and he was plagued by strikes of other municipal employees which crippled services sanitation workers, teachers. In his bid for a second term he had to run as the candidate of the Liberal Party, as the Republican party selected, Marchi, an arch-conservative for their ticket - an early harbinger of where the GOP was headed. Lindsay won not only because he was solidly supported by blacks, but also because his two opponents, both Italian-Americans, split those voters who detested him. He undoubtedly must have received the vast majority of gay votes as well, but in these years no one paid attention to what gay voters did.

Lindsay's second term was perhaps more ill-starred

than his

first . His advocacy of causes and policies on behalf of blacks and Hispanics

made him unpopular not only with working class whites, but middle class whites

and other politicians as well. His attempts to clean up the lower levels of

government and the police force made him even more unpopular when a two-year

investigation brought widespread corruption to light.

. His advocacy of causes and policies on behalf of blacks and Hispanics

made him unpopular not only with working class whites, but middle class whites

and other politicians as well. His attempts to clean up the lower levels of

government and the police force made him even more unpopular when a two-year

investigation brought widespread corruption to light.

1970's Upper West Side - when

the IRT had graffiti

and gangs of tough guys with cojones ruled the night.

(from imgur.com)

He was reviled for his liberalism, and branded the "Red Mayor." The cleanup operations after catastrophic blizzards, soaring oil prices and a doubling in the welfare rolls; combined with the costly packages to settle labor disputes - added to the past debt his administration had inherited were a recipe for fiscal disaster. When his second term ended at the end of 1973, no one gave a damn that he had made the city into a center of national and international tourism again and a magnet for arts and entertainment, nor that he had made Central Park safe and lovely again and a venue for free concerts. Or that he had also replaced the old weak lighting on thousands of miles of city streets with new high intensity lights which increased public safety. But he got the old New York treatment: Trow da bum oudda heah!

Ironically, Lindsay and his GAA nemesis went into the political dumpster almost simultaneously.

REFORM DEMOCRATS: BAD FOR THE "ETHNICS", GOOD FOR THE GAYS

The ascendancy of the Reform Democrats had pushed the working class, Tammany-loyal party members into the background, intensifying the anger they felt over the direction of the national Democratic party. At the same time the liberal Reform Democrats seemed to be creating an environment in which gay voters might find a place. The two Lindsay administrations served to underline for working class NYC voters that liberalism was their worst nightmare come true, and by repudiating Lindsay for an ultra-conservative Marchi the Republicans had recognized that fact. In the non-PC jargon of those years was emphatically: "No to niggers, no to Spicks, no to fags!!!"

For gays, who might have considered looking to the liberal wing of the Republican party yes, it did have one back then! Lindsay's departure was another symptom that this part of the party was on its death bed.

This was about the time that I changed my own party affiliation from Liberal to Democrat.

From a gay point of view the marginalizing of working class Democrats (often referred to now as "ethnics") was a plus, as they were usually conservative on social issues and more particularly, inclined to be very homophobic on the whole. However, I was aware, as were some of my friends and acquaintances, of conflicting feelings about this. We knew first hand about that hostility from our own personal backgrounds and usually had been delighted to escape for this reason; nevertheless, there were also happy memories and a nostalgia about our ethnic/working class origins. Our animosities toward aspects of our family and class backgrounds were specific, and while we wouldn't have wanted to "go back," so to speak many of us still had strong positive feelings about our origins too. However, gay guys from other socio-economic or religious backgrounds tended to see the "ethnics" (usually limited to traditionally Catholic groups) simply as evil bigots. Period.

In the latter half of the Seventies, when the makeup of the neighborhood had changed considerably, as had that of my group of friends, this contrast became more apparent. The "tone" of my social life worked in two modes. It had one quality when it included primarily people of WASP and Jewish backgrounds, and quite another when I was only, or mostly, with guys from working class Catholic backgrounds. This was something that worked in a casual, automatic way; and it was not until three guys, two from Protestant backgrounds and one a Jew - and they were not mutual friends pointed it out several times that I gave it much thought. One of them, John, who had been a psychologist by profession for a few years, was so observant about it that I tried to write it down later. "You guys [he was talking about four to half a dozen guys) talk in short hand sometimes when you're with everyone else....You have your own conversation going on, like in code, while you're talking with the rest of the room....I'm never sure whether you're doing it on purpose or not." Ah yes, in some respects this was like a more benign reflection of the bifurcation of gay life I had discovered back in Syracuse University. But whereas in Syracuse the campus guys and the city guys were almost unable to mix, in New York (and certainly in my life) there was a melding even if the differences were still there.

[I think that in the post-AIDS queer world European ethnic identification plays little or no positive part, and I wonder if pop culture and political correctness hasn't eroded the appearance though not necessarily the substance of social class differences as well.]

AND THE DEMOCRATS SHOOT THEMSELVES IN THE HEAD WHILE AIMING AT THEIR FOOT

In 1968, after the shambles that was the Democratic

convention, Richard Nixon had won the U.S. presidency. He implemented a

strategy of "Vietnamization" to end U.S. participation in the war.

The

main burden of combat would be returned to South Vietnamese troops allowing a

reduction in the number of U.S. troops, and thereby lessen domestic opposition

to the war in the U.S. all to be accomplished without undermining the efforts

of

the Vietnamese to defend their country.

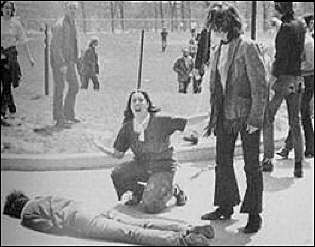

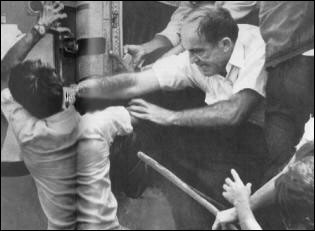

It could not be that simple, of course, and it seemed as if everything just unraveled

the massacre of Vietnamese women, children and old

people by U.S. troops was uncovered, Cambodia was invaded by the U.S. and became

totally destabilized, the Cambodian invasion caused a surge of protests and at

Kent State University and Jackson State National Guard troops and police shot

students to death.

the Vietnamese to defend their country.

It could not be that simple, of course, and it seemed as if everything just unraveled

the massacre of Vietnamese women, children and old

people by U.S. troops was uncovered, Cambodia was invaded by the U.S. and became

totally destabilized, the Cambodian invasion caused a surge of protests and at

Kent State University and Jackson State National Guard troops and police shot

students to death.

Kent State massacre by National Guard troops.

Vietnamese troops invaded Laos spreading the war to there, Australia and New Zealand withdrew their troops...and perhaps to quell dissent, large numbers of American troops were repatriated even as this went on. (One other result of the spreading destabilization of SE Asia was that the export of heroin and opium from the infamous "Golden Triangle" flooded not only Vietnam and the U.S. army with drugs, but sent waves of it for the first time into Europe and the U.S. for street sales.)

On the second night of the shambolic 1968 Democratic convention, the delegates voted for a commission which would seek to ensure that "all Democratic voters have had full and timely opportunity to participate." By early 1969, this appropriate and modest goal would be abandoned. For a variety of motives, largely having to do with bitterness over Vietnam and the Chicago convention mess, party reformers mostly associated with peace candidate, Sen. Eugene McCarthy abused the commission's mandate. Instead of following the mandate to reform the Democratic Party machinery, they set about to reinvent the party itself.

The new Democratic National Committee chairman Senator Fred Harris of Oklahoma didn't appoint any party hierarchs or persons representing their views to the commission, as had been promised. "I made up the membership of the commission in such a way as to ensure that [the commission] would come up with what they did come up with." Therefore the commission was stacked with party reformers, many of whom were deeply opposed to the war. The commission became a "fix."

It was headed first by Senator McGovern, from whom it receives its name.

And perhaps not just by chance, McGovern himself won the 1972 party

nomination, looking like a made-to-measure candidate of the

reformers. The twenty-eight-member panel became the means by

which antiwar liberals revolutionized the Democratic Party.

which antiwar liberals revolutionized the Democratic Party.

(right) Fred Dutton

Fred Dutton, manager of Bobby Kennedy's '68 campaign and author of the minority peace plank at that year's convention, emerged as the architect of this feat. His goal involved putting an end to the New Deal coalition of Franklin Roosevelt, the electoral alliance which had supported the party from the early 30's around a broad working-class agenda. In its place, Dutton sought to build a loose peace constituency, a collection of groups opposed to the Vietnam War and more generally the military-industrial complex.

Although both Dutton and Kennedy had included blacks in their alliance in his '68 campaign, Kennedy himself looked to blue-collar whites and white ethnics too for his main support a continuation of the New Deal model. But the new coalition was modeled on the one created by Eugene McCarthy, whose support was primarily among the young and college-educated. To this end, Dutton decided that Democrats would need to appeal to three new constituencies young people, college-educated suburbanites, and feminists, while ceasing to woo two old ones Catholics and working-class whites. The Democratic party coalition of FDR was smashed, and its base virtually shown the door and ushered into the waiting arms of the GOP.

He used one proposal to engineer the emerging feminist movement into the Democratic party, and other measures to, in effect, help secular, educated elites wrest the party machinery from state and big-city bosses. The 1972 convention was significant in that the new rules put into place as a result of the McGovern commission also opened the door for quotas mandating that certain percentages of delegates be women or members of minority groups. In 1968, for example, 13 percent of the delegates to the Democratic convention were women, but in 1972, that number increased to 40 percent. And although these groups did support the antiwar position of the reformers, they expected support for their own specific interests. Discussions on abortion and gay rights entered the convention arena, which had the effect of loosening other groups' ties to the party. Some of the results led to bizarre anomalies, one Midwestern agricultural state had a delegation abundant in women and representatives from higher education, but lacking farmers, the New York State delegation reputedly had nine gay people, but had no representatives from organized labor.

The 1972 convention delegates of Dutton's new party were less representative of the party rank and file, and the American mainstream, than any delegations seated in the past! George McGovern remarked ruefully later, "I opened up the doors of the Democratic Party, and 20 million people walked out."

This led to a class shift in each party, as affluent liberals gained more power in the Democratic party, working class people moved to the Republicans. As a result, the now familiar spectacle emerged. The GOP distracted its rank and file with a non-stop Punch and Judy show promoting a Christian America of gun-toting citizens parading in the regalia and ritual of High Church Patriotism, while its professional politicians continued to keep a lid on taxes for high earners and went to bed with industry and big business. The Dems had worked hard to reinvent themselves, but in the coming years they were routinely putting on declamatory exhibitions of pious outrage for their African-Americans, feminist and gay and lesbian regulars, as the party elite of white, well-educated professionals were happily waltzing with Wall Street and the banking industry, interests not exactly favorable to their new party regulars. And by the 1990's the real power in the United States had passed into the hands of its corporate entities.

The McGovern commission's machinations helped create the modern presidential primary system. Perhaps most importantly, the commission changed the rationale for choosing presidential nominees: Picking a candidate who was likely to win became less important than choosing one who would attract voters in the primaries, and these lean more heavily toward socio-economic elites and special-interest groups than do voters in the actual presidential election.

The

1972 convention was one of the most bizarre in American history, with sessions

beginning in the early evening and lasting until sunrise the next morning, and

outside political activists gaining influence at the expense of elected

officials and core Democratic constituencies.

The

1972 convention was one of the most bizarre in American history, with sessions

beginning in the early evening and lasting until sunrise the next morning, and

outside political activists gaining influence at the expense of elected

officials and core Democratic constituencies.

Say guys,

you sure anybody's out there?

McGovern giving his 3 a.m.

acceptance speech.

George McGovern ended up delivering his acceptance speech at 3 a.m. It was the second televised debacle in a row for the Democrats. I found the shenanigans close to unbelievable. There was no way these people could win an election.

Republicans unrelentingly pointed to Senator McGovern as a radical leftist. He was unable to shake that characterization, regardless of the very dubious course of "Vietnamization" Americans paid little attention to him. Two weeks before the election Secretary of State Kissinger announced that "peace was at hand".

Despite the very widespread disgust with the war, Americans were clearly fearful to elect a president who represented such narrow constituencies with extreme left-of-center goals. However, McGovern was undermined by forces which ordinarily would have supported a Democratic candidate: mainstream Democratic regulars failed to embrace the party candidate; AFL-CIO president George Meany, an old school anti-communist, guided organized labor's desertion because he opposed McGovern's anti-Vietnam War position; and Jews feared that he was not pro-Israel enough. The result was one of the most lopsided elections in American history. McGovern was absolutely skunked he carried only Massachusetts and the District of Columbia, and his share of the popular vote was so puny that he received only 17 electoral votes to President Nixon's 520. The anti-war movement was numb: President Lyndon Johnson had bowed down before it, and the Democratic party had consecrated itself to it but Tricky Dick Nixon wiped his butt on it and came up a winner! As president, Nixon continued to play out the war according to his own agenda, and in a manner that strengthened and coalesced American patriotic sentiment so that while it was not blindly pro-war, it was thoroughly anti anti-war. When Nixon was ready, he simply abandoned the South Vietnamese.

Two major blows to the Democratic Left were that it disappointed blacks of the inner city, and it proved equally unable to foster self-confidence and security among whites with lower incomes. Too much was invested and far too much jettisoned in trying to turn the Democratic party into the "peace party." But its most grotesque blunder was that it allowed the Right to co-opt Patriotism. Student demonstrators were enchanted with burning the American flag as a protest. And in trying to embrace and lead anti-war sentiment without unequivocally disavowing flag burning the Democrats became associated with disloyalty. And that stigma has stuck. In the decades following these events the Democrats were unable to consistently attract and hold centrist voters, and steadily lost membership through a failure to identify and articulate long-term economic issues.

While the Democratic party became progressively weaker and disorganized from this point, gay people in New York City went on to make a place for themselves in it, and in city politics too, after these local and national events came to pass. And in what are now called "blue states" gay people have also become a presence in elective offices.

In my college years among the many assigned readings were A Generation of Vipers by Phillip Wylie, The Hidden Persuaders by Vance Packard and The Lonely Crowd by David Riesman. The social trends and changes explored in these three books, all written before 1958, were already demonstrably among the strongest forces in American culture and society in the Sixties. Then the Vietnam War fractured America like no other event since the Civil War, and in the fall-out the old Democratic party was gutted while the Republicans reaped rich rewards by cultivating extreme social and religious conservatives. By the mid-Seventies all the forces, which have shaped the United States as it exists in the 21st century, were in place and potently active.

In 1974 New York City congressional representatives Ed Koch and Bella Abzug introduced a measure in the House which would have protected gay men and lesbians in the workplace. It did not succeed, but the battle for gay equality had been joined on the national stage. By the end of the century, legislation guaranteeing gay people equal opportunity in employment and housing still existed in only one-third of U.S. states; nevertheless, gay political energies and money were redirected. First, to the grossly miscalculated attempted reform of the armed services policy toward gay people in the early 90's, which resulted in the implementation of a new policy under which more people were discharged for their sexual orientation than under the old system. (The new Don't Ask/Don't Tell policy was rescinded in 2011 almost two decades after its enactment.) Second, gay rights activity then focused on same-sex unions, but the goal of legal same-sex unions was soon abandoned for that of same-sex marriage. The, by then, enormous power of conservatives and Far Rightists retaliated with the anti-gay Defense of Marriage Act which became Federal law in 1996. By 2010 seven states unequivocally allowed and recognized same-sex unions; however, the Rightist backlash was far stronger by that same year 29 states had amendments in their constitutions which restricted marriage to one man and one woman, while 12 others had enacted laws restricting marriage on the same basis. However, the U.S. Supreme Court in 2015 did come down on the side of same-sex marriages.

The Democratic Party in the more than four and a half decades following the McGovern Commission coup became an ever-increasingly smug, self-righteous political creature, one dangerously out of touch with too many white Americans. This would culminate in the catastrophic defeat of 2016 which stretched from the White House through both houses of Congress to the majority of state governments.

GAY KULCHA - HIGH AND LOW

While I was living in the House of Flowers I began putting things I thought I shouldn't throw out, or things I didn't want to throw out into an empty stationary box a "trick book" I kept that year, unemployment books, invitations, letters, clippings and over the years, I would periodically go through these odd bits, sentencing some to the waste basket and supplying a sturdier, and usually larger storage box for the remainder.

For almost thirty years two magazine

articles published a few months apart in the beginning of the 70's part of this

cache.

Both were personal essays, the first appeared in the September 1970 Harper's Magazine. I

didn't read the magazine regularly and was unaware of it until the wave of anger

and fear that it provoked reached me a few weeks after it came out. Someone

gave me his copy, and I read "Homo/Hetero: the Struggle for Sexual

Identity" by

Joseph Epstein. (He was a dapper academic who went on to be editor of The

American Scholar for many years, a "cultural critic" and a mediocre fiction

writer.)

Identity" by

Joseph Epstein. (He was a dapper academic who went on to be editor of The

American Scholar for many years, a "cultural critic" and a mediocre fiction

writer.)

Joe Epstein, wishing gays away.

In his jeremiad Epstein began with "hedonism," but then settled in on homosexuals who had been "cursed....with evil luck," which he characterized as a state of "permanent niggerdom." (Yowsa, boss!) Nowhere, that I recall, did he recognize seething homophobia such as his own as causative.

He did, however, have a solution an startlingly final one for a Jew had he the power he would "wish homosexuality off the face of the earth." How one would do that without wishing homosexuals off it as well, he did not explain. Reichsfόhrer Hitler had had the same aspirations for a Jew-free utopia, and he left working out the nasty details to others too; so perhaps it is unkind to fault Mr. Epstein on the details of his wishing away. Midge Decter, the magazine's managing editor, although a Jew, failed to see that similarity and was stoutly behind the Epstein article; not surprisingly she would author an equally poisonous one in 1980, "The Boys on the Beach." It was Gore Vidal who pointed out the parallel for their benefit. GAA pulled off a sit-in type protest at Harper's with considerable skill and humor; it lasted most of the business day and attracted TV coverage.

The other article I saved had appeared in the New York Times Magazine one Sunday in early January '71 as a direct result of Espstein's vilification. Merle Miller, a respected biographer of Presidents Truman and Lyndon Johnson, wrote a 7-page essay, "What It Means To Be a Homosexual." His was a thoughtful, unsensational response, and received a widespread positive reception. His most memorable comment: "...you cannot demand your rights, civil or otherwise, if you are unwilling to say what you are." Miller's Times essay probably got considerably more exposure than the Harper's piece.

In the Spring of '71 my friend Don P. and I went

to see Edward Albee's All Over at the Martin Beck Theater. Albee was an

openly gay playwright, though this play had no gay aspects. His star had

been rising since his early successes, Zoo Story, The Death of Bessie Smith,

The Sandbox and An American Dream in the late Fifties and early

Sixties, and Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf (1962) had earned him a Tony.

American Dream in the late Fifties and early

Sixties, and Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf (1962) had earned him a Tony.

Edward Albee, 1963 Showbill

All Over was a resounding thud, and some pundits declared that Albee was washed up. The next year we went to see his play Seascapes, which fared somewhat better. Contrary to those predictions, however, Albee continued to create interesting new work, and new productions of his older work have taken place around the U.S. and the world over the years. He has also been generous in sponsoring workshops for developing young writers.

The

openness that had begun mainstream media and the arts in the Sixties increased,

and it included the subject of the lives of gay men and women. Movies and

television probably got the most exposure. I saw Midnight Cowboy ('70)

and Sunday, Bloody Sunday ('71), both of which received critical acclaim

and did well at the box office.

The

openness that had begun mainstream media and the arts in the Sixties increased,

and it included the subject of the lives of gay men and women. Movies and

television probably got the most exposure. I saw Midnight Cowboy ('70)

and Sunday, Bloody Sunday ('71), both of which received critical acclaim

and did well at the box office.

Loud family, Lance at back left

That hot air balloon masquerading as a sacred cow, the American family, took a couple of reality hits early on. Look magazine (the former rival to Life as a photo magazine) included a gay male couple in a 1971 issue on the American family. Gasp, no! The American family became something of a dark comedy with pratfalls in a nine-part PBS special in '73, An American Family. A nice suburban family, the Louds, literally fell apart during the course of the filming, and the ultimate zinger was when teenage son, Lance, came out to his family as gay. Quite a journey from the sit-com fantasies of the Fifties!

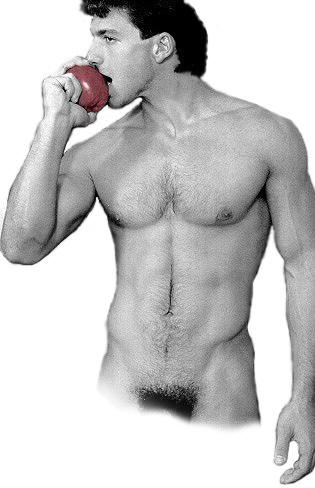

Paul Morrisey of Andy Warhol's in/famous "Factory" filmed the enigmatic and

voluptuous Joe Dallesandro in Heat in 1972, completing a trilogy of films

which began with Flesh and Trash. These helped make "Little Joe,"

the former nude physique model and prostitute, into a sleazy, sulky male sex

symbol in the underground film world with a huge following male and female.

Paul Morrisey of Andy Warhol's in/famous "Factory" filmed the enigmatic and

voluptuous Joe Dallesandro in Heat in 1972, completing a trilogy of films

which began with Flesh and Trash. These helped make "Little Joe,"

the former nude physique model and prostitute, into a sleazy, sulky male sex

symbol in the underground film world with a huge following male and female.

(right) Joe and the Sticky Fingers cover

After Dark was more delirious about him than ever. The Stones '71 Sticky Fingers album used a Warhol shot of Joe's basket on the cover, and in 1984 the Smiths used a still from Flesh as the cover of their debut album. The Sticky Fingers cover caused a furor and some stores refused to display it.

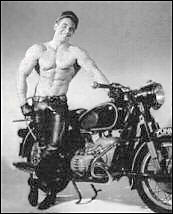

Fred

Halsted, S&M aficionado and XXX film actor, emerged as a director rivaling Kenneth Anger in the genre of gay

art-erotica. L.A. Plays Itself (1972) was his take on the same

territory as Anger's

Scorpio Rising. When it opened at the 55th Street Playhouse,

doubled billed with his Sex Garage, it was a case of see-it-now, or now

you don't. The police shut it down not for the notorious fisting

vignette that climaxes L.A. Plays Itself (which is cut from the video

versions that I have seen), but for a scene in which a guy gets it on with his motorcycle.

Fred

Halsted, S&M aficionado and XXX film actor, emerged as a director rivaling Kenneth Anger in the genre of gay

art-erotica. L.A. Plays Itself (1972) was his take on the same

territory as Anger's

Scorpio Rising. When it opened at the 55th Street Playhouse,

doubled billed with his Sex Garage, it was a case of see-it-now, or now

you don't. The police shut it down not for the notorious fisting

vignette that climaxes L.A. Plays Itself (which is cut from the video

versions that I have seen), but for a scene in which a guy gets it on with his motorcycle.

John Tristram, photo by Scott of London (aka Tom Nicoll)

In '75 Erotikus, a very well done and often quite funny history of gay porn films from the era of the posing strap to the mid-70's, featured Halstead as the hunky, ultra-cool narrator. He played his part from a director's chair, and as the movie progresses each time it cuts to Halstead he is wearing less clothing, until at the appropriate historical moment he flops a large erection out of his jeans. The film's most unforgettable scene is a clip of a blond young man on his knees in bed, straddling a dildo and not very successfully attempting to wiggle his way onto it as the Supremes sing Ain't Nothin' Like the Real Thing. Surely the funniest scene in 20th century film porn.

In

'73 The Faggot! by Al Carmines, the musical-writing minister at Judson

Memorial Church, got rave reviews from Clive Barnes the theater critic for the

New York Times and Vito Russo of Gay, among others and was still

selling out after its three-week run at Judson. It moved to the Truck and

Warehouse Theater (where I saw it with the usual group of suspects from the

neighborhood.) Bruce Mailman, later of St. Mark's Baths and Saint disco fame,

was a co-producer. I always enjoyed Carmine's sense of humor, but this was

truly special. There was even a commercial recording of this musical.

In

'73 The Faggot! by Al Carmines, the musical-writing minister at Judson

Memorial Church, got rave reviews from Clive Barnes the theater critic for the

New York Times and Vito Russo of Gay, among others and was still

selling out after its three-week run at Judson. It moved to the Truck and

Warehouse Theater (where I saw it with the usual group of suspects from the

neighborhood.) Bruce Mailman, later of St. Mark's Baths and Saint disco fame,

was a co-producer. I always enjoyed Carmine's sense of humor, but this was

truly special. There was even a commercial recording of this musical.

Carmines died in August 2005. In 2000 he wrote the following for a service celebrating Judson House, a historic building which had been used by the church as a health center, student housing, staff housing and other purposes. He wrote: