When My World Was Young 1945-56 The Yellow Brick Road 1956-60 What a Wonderful Town 1960-61

Wonderful Town (pt. II) 1962-66 The Gay Sixties 1966-70

The Juicy Life 197-76

Juicy Life (pt. II) 1976-80

Losing Alexandria 1981-87

The AIDS Spectacle

Losing Alexandria (pt. II) 1987-1990's

LOVE AND MARRIAGE...SORTA

I met Ken Hinaman on Memorial day '66 at Riis Park. After a bit of very indecisive checking each other out late in the day on the beach, I went back to the locker rooms to get ready to go home. We glimpsed each other there again, but the magnetism must have been inhibited by the dampness, I thought, since he left abruptly. But he was leaning against one of the pillars of the front portico when I came out, and he came over immediately and said with an edge of exasperation, "Do you want to go back together or not?"

We did, and he came back to my apartment to trick. That might have been it, if I hadn't found a nice greeting card stuffed in my mailbox a couple of days later with a message asking me to call him.

This summer was the beginning of my working permanently in the suburban offices of Fairfield Reading, and we began going to Riis Park together every Saturday and Sunday, and meeting for dinner sometimes during the week and sex, of course. Without thinking about it, the relationship took over and I stopped going to bars and tricking.

Ken lived in a large rent-controlled apartment in a

decently maintained old twelve-story building on the corner of 72nd

and Riverside. The next building was a five-story townhouse which had been

turned into a mosque; so, from the bedroom at least there were great views of

Riverside Park, the Hudson River and the Jersey Palisades. Ken's roommate had

moved out, and he was interviewing replacements with no success.

Ken lived in a large rent-controlled apartment in a

decently maintained old twelve-story building on the corner of 72nd

and Riverside. The next building was a five-story townhouse which had been

turned into a mosque; so, from the bedroom at least there were great views of

Riverside Park, the Hudson River and the Jersey Palisades. Ken's roommate had

moved out, and he was interviewing replacements with no success.

305 West 72nd St.

Earlier that spring I had moved from sharing an apartment on West 81st to living in another one upstairs by myself. But one day I came home to find that someone had dismantled the door of my old apartment and was in the process of burglarizing my former roommate. I chased the guy up the street, but didn't catch him. The incident upset me, of course, as it wasn't clear at this point that my traveling days were completely over; I was worried about leaving my new apartment unoccupied for weeks at a time in the event I did have to go out of town.

If it hadn't been for that burglary things might have worked out differently, but when after several weeks Ken was totally disgusted trying to recruit a roommate, one of us brought up the idea of my moving in. And in September '66 I moved into his place down on West 72nd.

This did solve the immediate living problems

of each of us,

but, as I recall, we never sat down and discussed what our relationship was

before moving in together. But living together, sleeping together, going out

together all the time to the exclusion of anyone else, took us right into the

territory of "couple," nevertheless.

This did solve the immediate living problems

of each of us,

but, as I recall, we never sat down and discussed what our relationship was

before moving in together. But living together, sleeping together, going out

together all the time to the exclusion of anyone else, took us right into the

territory of "couple," nevertheless.

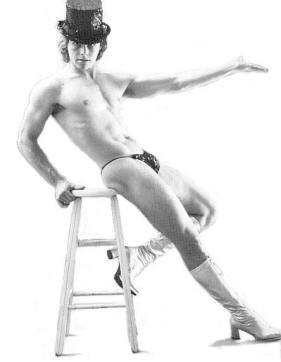

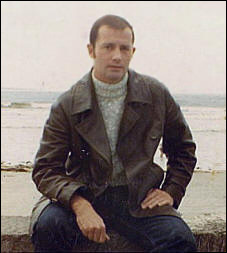

(right) Ken, 1969

Like most gay men in those years the idea of being a couple was lifted entirely from straight male-female life, replete with all the Hollywood movie romantic frosting and traditional social assumptions of het life there was no consideration to what degree these models were appropriate to two males.

Males, however, were raised with the expectation that they would become self-sufficient adults equipped to provide for themselves in life, and, in due time, for a spouse and children. The economic and decision-making role of a wife was considered to be secondary. When two guys became involved in a couple relationship, even when sharing a living space, their training to be the primary (or more powerful or responsible) partner in a couple relationship was at odds with this equation. The cultural assumptions about there being a "little woman" or subordinate role in a couple relationship would frequently meet with a lot of not-me-big-fella resistance when those expectations got aimed at another guy. Rarely was either partner prepared to just go along with "husbandly" assumptions from the other, and the jockeying around and deal-making had more in common with Sports Illustrated than Good Housekeeping and Modern Bride.

While tales of love relationships reaching across to the "wrong side of the tracks" or stories of happy kept boy arrangements abound, what I saw among guys was that they jealously guarded their individual money. Expenses were almost always split fifty-fifty even when there was an income disparity which might have suggested different proportions, and this was a major way in which a large number of gay men jettisoned some of the het tradition.

Even among heterosexuals there rarely seemed to be any consideration of whether the current heterosexual ideal of marriage as a sexually exclusive, monogamous arrangement might just be the institution of a particular time, place, culture, etc., rather than something intended, much less demanded, by Nature (or a deity.) The feminism of the era made for provocative magazine articles and lots of intellectual talk-talk....but the Real World carried on with the same ol' same ol'. And gay men were a big two steps behind on this score, never considering whether traditional het arrangements made sense for same-sex couples.

I did become aware a few years later that in the world of leathermen, there seemed to be some questioning and rejection of the heterosexual marriage ideal. Ken and I, however, did no such thing. What had started out as good sex and pleasant companionship had become living under the same roof as a couple and a whole lot of unexamined baggage came along with that.

Ken's job was doing publicity and public relations for a group of national touring companies of Broadway shows. This meant that he went on long-distance trips for two or three weeks every now and then. It was while he was on one of those trips in the early part of the following year that I discovered a gay bar in the neighborhood, the Candlelight Lounge. (And a few months later I went down to the Village with Arthur and his gang of friends to a new dance place called the Stonewall.) I resisted temptation for awhile, but then I picked up a trick in the neighborhood place, and then another and Ken on his trips did the same, I learned later. We both maintained the attitude that this conduct was wrong, and both of us took pains to conceal it the other, and both of us saw these promiscuous adventures when they came to light as threatening betrayals. But the script in our heads was a het-land fantasy almost worthy of Family Circle magazine. The amount of mutual hypocrisy and self-deception was preposterously stupid, and as it accumulated over the years it was far more of a problem than the extra-curricular sex itself.

There was one big difference in our conduct, though. Ken's tricks were one-off events out of town; whereas, mine were people we could very likely run into in the neighborhood when we were out together. Furthermore, as the months and years went on I was developing a circle of new friends and acquaintances, which because it had its origin in the gay bar while Ken was away were not mutual friends. And since these guys were associated with my extra-curricular sex, it seemed impossible to bring them into our shared life without creating a lot of ill will between us. Thus, as a couple we socialized with some of his old friends, and a small number of my old friends, but my new friends, who were becoming a major part of my life were not in the picture at least not in our picture as a couple.

EARL

In

the late Sixties one

of the guys I met in the neighborhood was Earl, the sexually hypertrophied "Redneck" who I had

connected with that early spring morning on Central Park West just before I had

met Ken. Not long after Ken and I started living together I stopped

into the corner drugstore on the NW corner of Broadway and 72nd, and

when I took my purchase from the LP bargain bin up to the cash register the

first Mamas and Papa's recording, the one with Monday, Monday there he

was. While Earl's mule-like endowment was impossible to miss, his

personality loomed as large upon renewed encounters. He had been born

in the southern Appalachians, and left the holler that was home sometime in his

teens. Over the years he had moved from place to place up through the southern

lowlands to the Virginia Tidewater country, until finally he and a lover made

the big jump to New York City. He was in his mid-thirties, with a face

that looked like it was chopped out of wood with an axe homely as the

proverbial hedge fence, and he stood well over six foot, all bone and sinew. Earl had had little schooling

and his

travels had made him cautious and crafty, but he was wise and full of wit as

well, a part of himself he ordinarily kept hidden behind a laconic exterior.

In

the late Sixties one

of the guys I met in the neighborhood was Earl, the sexually hypertrophied "Redneck" who I had

connected with that early spring morning on Central Park West just before I had

met Ken. Not long after Ken and I started living together I stopped

into the corner drugstore on the NW corner of Broadway and 72nd, and

when I took my purchase from the LP bargain bin up to the cash register the

first Mamas and Papa's recording, the one with Monday, Monday there he

was. While Earl's mule-like endowment was impossible to miss, his

personality loomed as large upon renewed encounters. He had been born

in the southern Appalachians, and left the holler that was home sometime in his

teens. Over the years he had moved from place to place up through the southern

lowlands to the Virginia Tidewater country, until finally he and a lover made

the big jump to New York City. He was in his mid-thirties, with a face

that looked like it was chopped out of wood with an axe homely as the

proverbial hedge fence, and he stood well over six foot, all bone and sinew. Earl had had little schooling

and his

travels had made him cautious and crafty, but he was wise and full of wit as

well, a part of himself he ordinarily kept hidden behind a laconic exterior.

Earl had a true gift for effortlessly spinning out tales of his adventures often side-splittingly funny, but punctuated with ironic observations and pathos the like of which I wasn't to encounter until I read Flannery O'Connor many years later. The relationship with his lover seemed to be totally open, and not something that interfered with his seeing me, and he had no interest in mine with Ken. Earl and we saw each other on a catch-as-catch-can basis for a couple of years. He was a fascinating guy, and for all of his rough-hewn exterior, he was a thoughtful and affectionate person.

Earl was not someone whom I would have expected to meet in New York. But he was one of maybe half a dozen or so gay guys I met on the Upper West Side in the late Sixties and early Seventies who had more or less similar Appalachian backgrounds. I had only three cousins on the maternal side of my family, two of them guys. They grew up on a farm in the hill country south of the small town where I lived, and now grown up they still lived up there in dirt-road country. While meeting Earl in New York City was a surprise to me, in some ways he could have been one of these cousins.

* * *

One of the greatest pluses I've found in being gay is the tremendous variety of people that I have met and shared my life with. Judging from what I observed in the lives of straight people in the Sixties, Seventies and Eighties, as a general rule the gay guys I knew on the Upper West Side usually had a far wider variety of people in their social (and sexual) lives than straights I worked with.

White guys sleeping with men across color and class divisions seems to be sniffed at suspiciously by some academics nowadays as evidence of sexual opportunism, or "sexual colonialism" if one prefers a trendier PC term. But it was my personal experience, which was matched by that of my friends, that many of the people who became my friends and acquaintances came from the ranks of guys who were tricks first and this certainly included some guys who were of a different race/ethnicity, social class background, etc. than myself. While New York gay life was not a Liberal PC Utopia in the late Sixties, the majority of the bars I went to had mixed crowds (though how mixed varied, of course), and informal social gatherings outside of the bars, as I remember them at this time, often included Hispanic guys (of various skin colors), though few or no blacks. Of course there were gay white gay men who fastidiously "stuck to their own kind," however, on the Upper West Side and in the Village too, I don't think that this was the predominant lifestyle. Guys who were seriously under-educated or in some cases just plain not too bright had the usual tougher row to hoe though this was more the case socially than sexually. Earl, for example, was quite aware of his poor education and lack of connection to/awareness of what I guess would be called mainstream culture, and I felt that he hid behind an exaggerated "yep" and "nope" hillbilly facade in public for this reason.

It may also have been around this time that I came across a magazine article on monogamy more especially the sexually exclusive aspect of it. It may have been in Psychology Today, which was having a lot of success as a new publication. It was the first time I had read anything like it, an open discussion of various points rather than a polemic insisting on monogamy as the crowning achievement of Western Man. I made some check marks on it and underlinings, and then threw it in a drawer to read again later. When I did come across it again, I discovered that Ken had seen it in the meantime, and he had made his own tick marks and written some comments. As a result, we had some awkward but helpful talks about the extra-curricular sex aspect of our relationship.

Despite the deceit about sex, and consequent ill

feeling that would flare up as a result, our relationship on the whole was a pleasant and

cooperative one. We finished off fixing up the apartment, and bought some

additional furniture and most week nights we ate in and spent our time together

reading or watching television. We decided to give the New York City Opera a try

at one point, and bought tickets for the fall season neither of us were even

remotely opera buffs. I think I had only seen one or two performances at the

Amato Opera on the Bowery. It turned out to be something we both grew to enjoy

though we weren't made to be "opera queens" and we ended up subscribing for

both the fall and spring seasons for three years. We used to go down to the Village to

eat out on Saturday nights, usually to the Five Oaks on Grove Street, down

a long flight of stairs into the basement. It was a small place with a

passionately dedicated clientele, a good share of it gay men and women.

The food was fine, but finer was sitting into the smoky night listening to

pianist/singer Marie Blake and the entertainers she attracted. It was part

of the vintage sophistication of Greenwich Village.

We also went to a gay

village landmark of the era, Mona's Royal Roost on Cornelia Street. The

decor was 1890's whorehouse - red flocked wallpaper with brass and phony crystal

light fixtures. The very Mona herself reigned from a back table, a portly

woman with peroxided hair, who wore beaded floor-length dresses. Usually

attended by two or more courtiers, she would when well lubricated, which was

most nights, unintentionally inform the diners in a rising voice, well-worn from

booze and cigarettes, which "goddamned son-of-a-bitch" had tried to put one over

on her that week and how she had fixed his or her ass.

We also went to a gay

village landmark of the era, Mona's Royal Roost on Cornelia Street. The

decor was 1890's whorehouse - red flocked wallpaper with brass and phony crystal

light fixtures. The very Mona herself reigned from a back table, a portly

woman with peroxided hair, who wore beaded floor-length dresses. Usually

attended by two or more courtiers, she would when well lubricated, which was

most nights, unintentionally inform the diners in a rising voice, well-worn from

booze and cigarettes, which "goddamned son-of-a-bitch" had tried to put one over

on her that week and how she had fixed his or her ass.

And then as Columbus Avenue began to gentrify commercially we went to the Red Baron in our own neighborhood too - unfortunately this gentrification did not bring with it any Marie Blakes, nor even a Mona. Both would have been pluses.

THE FAMILY CIRCLE

The relationship with my father, which had been a troubled one since late grade school and had become a loathsome chancre for both of us after he found out I was gay, came to an end in August 1967. An unloving, distant, and often ominously silent man, he sat then in a chair in his hospital room, gestured with his hands and mouthed words but as he had cancer of the trachea he could not speak...when he finally wanted to. I helped him into bed, he had a shot of morphine and we stood there and watched him go to sleep and die.

My mother panicked that I would desert her as she had been as homophobic as he had been, and worse it had been she who had tormented me with a steady stream of rebuking letters. Now she did a huge about-face, blaming him for everything; even coming to NYC to stay at the apartment with Ken and I for a long weekend with my aunt! The aggressive homophobia was on hold for almost four years, though she was constantly criticizing her sister, my now widowed Aunt Marie, But then my mother hooked up with my childhood dentist and he asked her to marry him: SPLAT!!! the same ol' shit suddenly hit the fan again. I received a disgusting letter telling me that he would divorce her if he found out about me, etc., etc., etc. I hated her for this turn-around.

But my mother had been a spoiled child and never grew into a mature adult; mendacity was one of her marked traits I had been very stupid to believe she would keep up her "reformed" act for any longer than served her purposes. She was a lifetime thirteen-year-old in the content of her character.

And so she was again the same homo-obsessed nut that she had been in the early Sixties. I was the enemy within, whose homosexuality would destroy her marriage if her new husband found out. I tolerated this any love for her had died when I was in college, but now even respect died. I continued the relationship with her only because I wanted to protect the relationship with my Aunt Marie, her sister, whom I loved very much. My mother was, if anything, even more jealous of our relationship by this time.

[When the AIDS epidemic arrived years later she declared fearfully that I could not come down there (a small retirement town in Florida) to stay if I was infected. I had never suggested the possibility. Even if I had AIDS, why would I want to go to a place with no medical facilities? And...and...and.... After a especially noisome letter in 1987, I told her that I would never communicate with her again as long as she lived. Once in 1999 we exchanged brief letters when I was preparing to emigrate, and she died three months after I left the U.S.]

A LITTLE DOPE, AND SOME DOMESTICITY

By 1968 Ken had a plum of a new job working for a top show business public relations firm, and in the spring he was working with Gore Vidal, who had a new play opening on Broadway. In late spring he began work for one of their major new clients, the Saratoga Performing Arts Center located in an old spa town near Albany. This was a major turning point in the relationship. He was away for about three and a half months, during which time my neighborhood social and sexual life bloomed. At the same time, Ken met new gay friends working up at the Saratoga Center. And he became involved in a summer-long affair with Steve (who had had a lover for a several years), who was also working in Saratoga for the summer.

Following that summer Steve from Saratoga and his lover, George, visited the city several times a year and stayed with us. They were bright and congenial guys, and the four of us became friends.

I went up there for one weekend. Ken smoked

marijuana once in awhile. I think he started a year or so after we began living

together. I'd had no

strong curiosity about grass, but I tried it just not be a wet blanket

and zip, nothing happened.

I went up there for one weekend. Ken smoked

marijuana once in awhile. I think he started a year or so after we began living

together. I'd had no

strong curiosity about grass, but I tried it just not be a wet blanket

and zip, nothing happened.

(right) Photo from 1936 film melodrama "Reefer Madness."

This particular weekend we smoked before having sex. Afterwards Ken asked, as he had in the past, whether I'd gotten high. I mumbled something non-committal, and then added, "but sex seemed to take so looooong!" (It wasn't a complaint.) He laughed, "You finally got high."

I blew grass regularly for the next twenty years. (It is probably worthy of note that over this period of time the quality of grass being sold increased enormously.)

Despite the

glories of Timothy Leary's gospel of "turn on, tune in and drop out" as

propagated by the Hippies in the latter part of the 60's, I was not attracted by

the idea of hallucinating.

Despite the

glories of Timothy Leary's gospel of "turn on, tune in and drop out" as

propagated by the Hippies in the latter part of the 60's, I was not attracted by

the idea of hallucinating.

1966 Newsweek cover story on LSD

Moreover, it seemed to me that being gay was providing all the opportunities I needed to "drop out" and essentially the LSD/Hippie/drop-out scene looked to be a playground for white, middle class twenty-somethings. I did, however, try Angel Dust somewhere around 1970, I guess, and had a very weird, but not frightening, experience; but when I tried it a second time it was practically a non-event. However, the bad press on "dust" and some anecdotes that came my way convinced me that I'd just been lucky, and I never did it again.

Ken got interested in cooking and wine on a rather

serious level, and a spin off of this was that we had people over for

dinner more and more often.

Gracious entertaining at home (from Fellini's Satyricon, 1969)

[In the future he would open a restaurant in Texas, and later one in Southern California.]

Ken had served his military service stationed in Germany and had managed to get himself discharged in Europe at the end of it, where he stayed and worked in Paris for a couple of years or so before returning to the U.S. As a result he had various foreign friends who visited us a couple of times a year.

Living with Ken gave me my first taste of domesticity and a conventional social life since moving to New York. Prior to this my living arrangements had been more along the lines of crash pad/college dorm, and the lack of a decent paying job had kept dining out and more expensive types of entertainment beyond reach. The idea of an apartment as "home base" now really had an emphasis on home. (Although being the Upper West Side there was still a "police lock" on the door as well as the regular one.) And, in addition to the new friends of my own that I'd made in the neighborhood, I enjoyed Ken's friends from his Saratoga summer, and even more those from his European years as I'd met or known only a very few Europeans.

For a couple of summers we took a vacation in the Fire

Island Pines for a week, renting on a Sunday through Friday basis from a friend

Ken's. Staying there was a much different experience from my two visits to the Grove, which I

hadn't been to for two or three years now.

For a couple of summers we took a vacation in the Fire

Island Pines for a week, renting on a Sunday through Friday basis from a friend

Ken's. Staying there was a much different experience from my two visits to the Grove, which I

hadn't been to for two or three years now.

A Pines boardwalk

The Pines was a far more attractive community the building lots were much larger, so the houses were farther apart, and on the lee side of the dunes they were usually surrounded by trees and undergrowth. The overall environment was quieter and more natural. And there seemed to be far less frantic, non-stop drinking going on. On the negative side, it was more expensive to rent there and prices overall were higher. However, while men such as Jerry Herman, the creator of several hit Broadway musicals, and Calvin Klein, the clothing designer, had impressive homes there, many places were rented to groups of far less affluent gay men who took shares in a house for the summer.

JUDY GARLAND

(NO SNEERING, IT'S THE 60'S. SHE HAD TO

BE IN HERE SOMEWHERE)

In August '67 Judy Garland played four weeks at the Palace Theater on Broadway. "Judy Garland Sets the Palace Alight" was the headline on the Times review, and the reviewer began by saying:

"Judy Garland returned to the Palace last night like some raffish, sequin-sprinkled female Lazarus. That magnetic talent is alive once again in New York, and so is one of the most remarkable personalities of the contemporary entertainment scene. That the voice - as of last night's performance, anyway - is now a memory seems almost beside the point."

She was, the night we saw her, not having any voice problems, and she gave an assured, confident performance these were things she could not always deliver toward the end of her career.

The evening was marred by the

interruption of one of her cult crazies. He stood up in the first row of the

balcony just as she was getting ready to begin a number and called out..."Judy,

I love you," or something similar. These occurrences weren't unusual at her

concerts, and she had made trading remarks with these fans part of her concert

shtick.

(right) Judy Garland at the Palace '67

This was a drag queen, however, who was wearing a copy of the sequined pants suit which Garland was wearing on stage that night. Garland's response was, "Loooove your outfit," with a perfect bitch-queen imitation. (Lots of laughter.) "Where did you get it?" The question proved to be a huge mistake, as this queen would not be turned off now, and despite the singer's best attempts at a polite kiss-off and stepping toward the center of the stage this queen was not giving up her claim to the air space. The audience was rumbling, and some people started calling for him to sit down, and very quickly most of the audience was shouting for him to shut up. Garland signaled the conductor, the orchestra struck up and she went on with the show.

It was an evening of great entertainment, and most of the audience gay and straight was leaving on a high. But we overhead several knots of Garland's more morbidly obsessed "fans" exclaiming, "Oh, I thought I'd die when she almost tripped over the mike cord," or "You could see her hands shaking so badly, that I just wanted to cry," ad nauseam. The performance these people saw certainly wasn't the one on the stage at the Palace that night, but rather the fantasy of a tragic shipwreck of which they were the lucky survivors and elegiac tale-bearers. They starred in their show, Garland in hers.

Judy Garland died two years later, June 1969, of what was ruled an accidental overdose of sleeping pills. Her funeral was private, but prior to that thousands of people lined up for hours to pay their respects. It is often commented that many of them were gay men, which is true, but most were women, middle aged and older, who had loved Garland as a movie star she was theirs too. Frank Sinatra said, "She was the greatest. The rest of us will be forgotten never Judy."

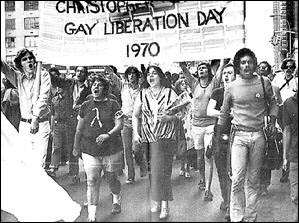

Ken and I marched in at least one anti-war march together, which was the Moratorium in '69, I believe, where I recognized other gay men from the neighborhood. Like a lot of gay men we followed the infighting in the NYC Democratic Party as the Reform Democrats became top dog, and pro-gay figures like Bella Abzug and Shirley Chisolm emerged.

Our relationship became more heavily weighted on the friendship side than the romantic-sexual one, and in early 1970 we decided not to continue the sexual part of it.

As far as I had known there were no gay bars on the Upper West Side after the early 60's purge. But sometime in '66 or early '67 I noticed a "suspicious looking" place. It was called Milano's, and it was across from Verdi Square near the northeast corner of Amsterdam and 72nd. There was nothing special about it to notice really, and I'd passed it a lot. But one day as I walked by I happened to glance at the window. There was a guy sitting there and he locked eyes immediately, and stayed glued to my eyeballs until I looked away. The bad news was he looked like someone you could to hire to knife your rich grandmother. I furtively glanced in the window a few more times when I had to pass, but either the bar looked empty or someone else from the Most Wanted list was checking out the street. My thought was that maybe the place got some rough trade as customers. Verdi Square had the well-earned reputation for being a gathering place for low life. Sherman Square, which was the area just south of the IRT subway entrance on W. 72nd was original "Needle Park", but Verdi Square on the north side of the street soon shared that nickname. (Milano's, I learned later, had been pretty much what I guessed available guys, but not trustworthy, some outright dangerous perhaps. Gay? Maybe, maybe not.)

Someone, and it may have been Ken, told me there was a gay bar a little further up Amsterdam Avenue. Whoever it was, I remember that they thought it was a truly lousy place. The street lighting was still only slightly brighter than a coal mine, and Amsterdam was a consistently dumpy part of the neighborhood. I wasn't sure how I liked the idea of checking it out alone at night in the event it turned out to be anything as uninviting as Milanos looked.

As usual second thoughts won out over what had seemed wiser ones. I found the place one night at mid-block on the east side of the Amsterdam, between 75th and 74th. The first time I didn't even go in. Though I could see a couple of men at the end of the bar, I could hardly make them out the place was so dark...I walked past a couple of times. No one came in or out. Uh-uh, I chickened out.

But it may have been the next night that I went back to reconnoiter again. There were more guys at the end of the bar, and a bald, gnome-like man with a doleful expression sitting in the window. Holy shit, even worse. But, then I saw someone, or maybe a couple of someones, going in or out, and decided they looked gay yeah, do it.

The place was called the Candlelight Lounge back then,

later it was just the Candle Bar. I was going there by February '67 so my first

visit might have been late the year before. The bar had been operating as a gay

bar before I started going there, which means I think that it

probably ended up being the oldest continuously operating gay bar in New York City. (Julius's in the

Village has been open much longer, of course, but for most of its history it was

a straight place. When it began attracting a noticeable minority of gay customers

in the 60's it kept up a steady campaign of trying to get rid

of them; so, until the Sip-in it's not appropriate, to my way of thinking, to

consider it a gay bar.)

The place was called the Candlelight Lounge back then,

later it was just the Candle Bar. I was going there by February '67 so my first

visit might have been late the year before. The bar had been operating as a gay

bar before I started going there, which means I think that it

probably ended up being the oldest continuously operating gay bar in New York City. (Julius's in the

Village has been open much longer, of course, but for most of its history it was

a straight place. When it began attracting a noticeable minority of gay customers

in the 60's it kept up a steady campaign of trying to get rid

of them; so, until the Sip-in it's not appropriate, to my way of thinking, to

consider it a gay bar.)

Candle Bar in 2006, for many years NYC's oldest continuously operating gay bar.

[It finally closed in 2015.]

The Candle in later decades looked much different inside than it did then. The building, and in fact most of the block, has been beautifully restored. The actual bar space was smaller as well. There was a bar with stools on the left side as you entered and enough room for an aisle to the back. The place got wider at the end of the bar. There was a juke box on the right and a mechanical shuffle board game. (The shuffle board game was obnoxiously loud and intrusive in such a small space.) There were booths with tables against both walls, and the middle of the room was crowded with tables and chairs. The tables were covered with red cloths. There was a men's room behind this on the left, and an unused kitchen on the right. The booths and tables weren't used a lot, and they wasted what could have been standing space for more customers.

The customers were a group of ordinary guys in casual clothes, mostly in their late twenties, I guess. It was clear from the buzz of conversation that a lot of them knew each other. I wasn't very comfortable as I got the feeling that I was one of the few people there alone. However, I did go back it was too convenient not to, a ten minute walk away.

Occasionally in these same years I went to the Old Vic on the East Side or the Stonewall or Kellers in the Village; and then later, the International Stud and the Snake Pit opened in the Village too, and I think even the Triangle was open by '69. (Stonewall and the Snake Pit both had good music and dancing.) In '71 I was still going down to the Triangle and the Zodiac sometimes and there was an after-hours place on Christopher, called Christopher's End. But more and more often in the late 60's I just walked over to the Candlelight Lounge. From 1966 on I almost never had to travel out of the city on my job. After living on the Upper West Side for most of my six years in New York, finally I was doing my socializing there and getting to feel that it was really my neighborhood.

The worried little gentleman I'd seen sitting in the window

was known as "Sweet William." The story was that he was there to keep an eye on

the place for the owners and/or that he was the front man whose name appeared

as the official licensee. His duties appeared to weigh heavily on him. He was

a short, stocky man, and periodically he would slide wearily off of his stool in

the corner by the front window and trudge through the bar, fingering a string of

komboloi/worry

beads and looking troubled. The bartenders treated him with a kind of jocular

deference. And after a time quite a few of the customers were greeting him as

he wandered through the place, which seemed to delight him. It had become

clear, I guess, that he was essentially just putting in his time. It had become

equally clear that his reticence and unhappy appearance were likely due to

terminal boredom. The story was that not only was he straight, but Albanian as

well, with only a nodding acquaintance with English. The real owners were

allegedly a Greek-American family who owned a restaurant on the Jersey shore of

the Hudson. And, indeed, there was a very brief period when a middle-aged Greek man and his young, attractive son appeared and took a hand at tending

bar. Despite doing their best to be friendly, neither they nor the customers

were truly comfortable with each other. They disappeared...as did Sweet William at some

point.

The worried little gentleman I'd seen sitting in the window

was known as "Sweet William." The story was that he was there to keep an eye on

the place for the owners and/or that he was the front man whose name appeared

as the official licensee. His duties appeared to weigh heavily on him. He was

a short, stocky man, and periodically he would slide wearily off of his stool in

the corner by the front window and trudge through the bar, fingering a string of

komboloi/worry

beads and looking troubled. The bartenders treated him with a kind of jocular

deference. And after a time quite a few of the customers were greeting him as

he wandered through the place, which seemed to delight him. It had become

clear, I guess, that he was essentially just putting in his time. It had become

equally clear that his reticence and unhappy appearance were likely due to

terminal boredom. The story was that not only was he straight, but Albanian as

well, with only a nodding acquaintance with English. The real owners were

allegedly a Greek-American family who owned a restaurant on the Jersey shore of

the Hudson. And, indeed, there was a very brief period when a middle-aged Greek man and his young, attractive son appeared and took a hand at tending

bar. Despite doing their best to be friendly, neither they nor the customers

were truly comfortable with each other. They disappeared...as did Sweet William at some

point.

The bar's owners were now said to be a couple known as Sonny and Jenny. Sonny Tobin, according to an unkind reference at one time or another in one of the tabloids, had been a minor figure in the waterfront rackets. Jenny would go on alone, Sonny having died to be the reputed owner in future years of several other gay bars in the neighborhood, and for this she got her own snide reference in the press in the early 70's...this time New York Magazine. Jenny witnessed Sonny getting gunned down in front of their home in late 1978, but she carried on managing what amounted to a gay bar realm of no small size by herself.

There were three night bartenders at the Candelight Lounge: Denny, the manager, was a soft-spoken fellow, tall, thin and nice looking, probably in his late thirties or even early forties. I can remember having a conversation with him once about the New York bars I went to in '59, but the ones he looked back on fondly were the Cork Club and Artie's from the early Fifties. Earl was short and very cute, in his early/mid-twenties and a bit though engagingly ditzy. And the other one, who became a friend in the early Seventies, was Larry Clinton. He was very tall and thin, with a kind of theatrically homely face, and a dry, but outrageous wit.

The day bartender was a lesbian named Maureen, or Moe. She would sometimes drop in during the early evening, though she rarely stayed long, being far too savvy not to know that women weren't good for business in a men's gay bar. I can only remember one female customer, who appeared for a brief period of weeks in the early evening sometimes. She was an older straight woman who worked as a bartender somewhere, and she told me she picked the Candlelight because she could drink there without men trying to hit on her. Very infrequently guys might bring in a female friend to the bar, but everyone knew that an extended visit was a royal road to unpopularity with the other customers.

[I never visited a lesbian bar. But on two different occasions in these years I did listen to some brief comments by different women about thoughts about men customer's in lesbian bars. Their idea of a straight guy coming in was on par with having a cockroach perched on your birthday cake. If a female patron brought a gay guy along, this was tolerated but not really welcomed. So, it seems attitudes were similar on both sides of the gay coin.]

I didn't go to the Candlelight Lounge habitually yet for a couple of years, and most of the people I met initially were pickups for sex. However, my first impression that the bar was a place where a lot of the people knew each other was right. The Candlelight Lounge was as much perhaps even more in these days a social meeting place as it was a cruise bar. This part of the Upper West Side was still dingy or worse, and no one was likely to come up there purposely to cruise in a bar, which meant the clientele remained a crowd of local guys. The atmosphere and energy of the place were low, curiously reminiscent of how I remembered many New York bars being in '59 and this was seven years later. Guys stood around talking quietly, for the most part their body language was restrained they could have been standing in a subway station. The music provoked some foot tapping or a little head bobbing. And some of it was the actually the same music certainly the same genre and artists as what I had heard when I first arrived in the city! The Candlelight Lounge was a bit of a time warp at this point.

Later, as the neighborhood improved and the gay population increased, other bars opened. There were many more people in the bars then who didn't know each other, and the amount of cruising activity rose. Still, some of these bars retained that quality of neighborhood center/social club for a core of customers. These were still the places a guy could go to find someone to paint his apartment, locate an inexpensive dentist, get an apartment cleaner, a mover, a resume written, etc. if your own friends didn't know, ask your casual bar acquaintances and tricks, and best bet asking the bartenders. And, of course, gay bartenders - even more than straight ones, I think - are famous for being confidants, confessors and shoulders to cry on for some of their customers, which is a draw of its own.

The Candlelight Lounge's customers were white Americans and Hispanics. My recollection is that a consistent quarter of the crowd was Hispanic (Cuban and Puerto Rican mainly), though that proportion could go higher on weekend nights. This was a change from previous places I'd hung out in, where I'd been unaware of Hispanics as being a large part of the crowd. There were only a very few blacks who came to the bar. The guys mixed and used the space with no regard for ethnicity. Cliques of friends were often composed of American and Hispanic guys, and the circles of bar acquaintances were completely mixed. Ethnicity didn't seem to play the slightest part in who tricked with who, and it may be that the tricking was actually the origin of the easy-going mixed socializing.

"Leave it to Little Mary Sunshine..."

I had seen the Off Broadway musical Little Mary Sunshine with some friends in 1962 at the Orpheum on Second Avenue, formerly a venue for NYC's once thriving Yiddish theater. Nowadays the show would probably be skewered as racist - or totally non-PC, at least - but it was a harmless send-up of the old Jeanette MacDonald Nelson Eddy romantic cornball movies of the Thirties and Forties. There are two American Indian characters in the cast, and at one point we were sitting in a front row I was unnerved to realize that one of them had his eyes glued on me. And in a later scene it happened again. A few days after one of my friends, who knew the actors, told me, "Oh, so-and-so was interested in you..." or something to that effect. And that was that.

One night in February '67 - five years later - I saw a guy in the Candlelight who looked familiar immediately, but I had no idea who he was. He saw me, and clearly recognized me. He came over, held out his hand and said, "Hi, I was the Indian in Little Mary Sunshine." Ah yes. And this time that was not just that.

The next night I was in the bar, an acquaintance who'd been standing next to me at the time said, "Jesus, that guy had some ego the way he introduced himself. You would've of thought he'd had the lead in Sweet Charity!"

After a couple of years (by 1969) I knew enough people in the Candlelight that I was going there regularly to hang out with the friends I'd met, as much as for the sexual opportunities though these were rarely lacking, and rarely declined.

The bulk of the customers were guys in their twenties or early thirties, with a very much smaller number being in their forties. Many of the guys had office clerical jobs, some had technical skills, and - typical of the Upper West Side population in general, I think - there were a fair number of customers connected with theater or the arts. I met only one guy there in these years who was well established in a profession or business and/or had a more than modest income. (Years later he had become a major figure in NYC cultural life and television.)

On the other hand, there were those guys who scrambled hard to

make a small living lunch counter waiters, stockroom clerks, porters,

handymen, unlicensed haircutters and a handful of guys who seemed more often

unemployed than not.

On the other hand, there were those guys who scrambled hard to

make a small living lunch counter waiters, stockroom clerks, porters,

handymen, unlicensed haircutters and a handful of guys who seemed more often

unemployed than not.

The Belleclaire

At this time some of the old, rundown hotels in the area of Broadway & 72nd St. area, (the Belleclaire, for one), were home for some of the guys I knew who were on the really low end of the job scale. (The Belleclaire, a gorgeous early 20th century building was to have even more horrible days as a welfare hotel in the 80's before being restored in 2004 to something like its former grandeur.) Like Larry, Don and I had done in the Tiltin' Hilton, these guys lived two and three together in order to make even these seedy accommodations affordable.

That all-important gay bar shrine in the Candlelight Lounge, the juke box, sucked. And it sucked big time. It contained an undistinguished menu of pop and rock with a very small dash of Motown. If it weren't for some Judy Garland, Billy Holiday and Dinah Washington, it could have graced a bowling alley in East Armpit, Nebraska. New songs that showed up were dying by the time they arrived and in some cases should have died before.

There was no Latin music on it either, despite the Hispanic patrons, but this always was the case in any Manhattan gay bars I went to over the years. It seems very odd, though, given the large Hispanic population on the Upper West Side at this point that it had not developed something like the current Latino gay scene in Jackson Heights/Woodside, Queens. The 415, a dance bar at Amsterdam & about 81st St., had been heavily Latino, but it was closed in '59. Perhaps there were Hispanic gay bars farther uptown on the West Side, but I do not recall ever hearing of any.)

This was not a jukebox you could have put into Stonewall or Kellers

during the late Sixties. Despite grousing by the customers, the jukebox improved with the

enthusiasm of a would-be suicide. The bartenders, Earl and Larry, parried

complaints without actually giving out any information about the source of the

problem at first, and if Denny, the head bartender, had anything to say on the topic he

must have said it very quietly. At some point, with a stagy "secrecy" and some

outlandish concealed finger-pointing, Larry identified the quiet and affable

Denny himself as the villain! Denny was not crazy about most rock music it

seemed, but he really disliked R&B and Soul. And as the manager he was able to

muzzle the juke box.

This was not a jukebox you could have put into Stonewall or Kellers

during the late Sixties. Despite grousing by the customers, the jukebox improved with the

enthusiasm of a would-be suicide. The bartenders, Earl and Larry, parried

complaints without actually giving out any information about the source of the

problem at first, and if Denny, the head bartender, had anything to say on the topic he

must have said it very quietly. At some point, with a stagy "secrecy" and some

outlandish concealed finger-pointing, Larry identified the quiet and affable

Denny himself as the villain! Denny was not crazy about most rock music it

seemed, but he really disliked R&B and Soul. And as the manager he was able to

muzzle the juke box.

I do remember when one Aretha Franklin song showed up - Chain of Fools, I think it was - and I poured coins into the box. It must have driven him mad. He probably wished I'd get hit by a truck on my way to the bar.

In the following decades the Candlelight Lounge/The Candlelight/The Candle went through several cheapo makeovers, but in the Eighties Robert Ader, a new gay owner, did a big renovation and so totally changed the atmosphere that the place could have easily fitted into Christopher Street or Chelsea. But the doyen of NYC gay bars is scheduled to do its final trick on June 22, 2015: to close its doors for the last time. And with that the final vestige of pre-AIDS gay life on the Upper West Side will disappear.

HAM & EGGS AND "THE GREEKS"

There were two places that people

went to eat after the bar closed at 4 a.m. (or 3 a.m. on Sunday mornings.)

There were two places that people

went to eat after the bar closed at 4 a.m. (or 3 a.m. on Sunday mornings.)

The Dorilton

One was the Ham and Eggs

restaurant on the east side of Broadway at 71st.

My recollection is that it occupied the corner commercial space of the Dorilton

apartments, an outrageous Second Empire tart of a building fallen on evil days, which had it been a person could only have been Zola's courtesan,

Nana. Ham & Eggs was a fairly large place, and pretty busy at that time of night. Many,

probably most, of the patrons were straight, but it usually attracted a small,

but conspicuously loud and showy crowd of a half dozen or so effeminate young

queens. They sat at the counter space nearest the door when they sat at all -

but were usually running back and forth to the street. They were slap queens

(slap = makeup), though a more daring one or two might show up in drag or an ambiguous

ensemble that bordered on it. They spent a lot of time on the pay phone, and

parading back and forth along the curb in front of the place - like tawdry,

street-walking versions of Zola's magnificent whore. The lucky ones might meet a john and get whisked away in a car. As I recall, the place closed

not long after I started going to the Candlelight Lounge.

One was the Ham and Eggs

restaurant on the east side of Broadway at 71st.

My recollection is that it occupied the corner commercial space of the Dorilton

apartments, an outrageous Second Empire tart of a building fallen on evil days, which had it been a person could only have been Zola's courtesan,

Nana. Ham & Eggs was a fairly large place, and pretty busy at that time of night. Many,

probably most, of the patrons were straight, but it usually attracted a small,

but conspicuously loud and showy crowd of a half dozen or so effeminate young

queens. They sat at the counter space nearest the door when they sat at all -

but were usually running back and forth to the street. They were slap queens

(slap = makeup), though a more daring one or two might show up in drag or an ambiguous

ensemble that bordered on it. They spent a lot of time on the pay phone, and

parading back and forth along the curb in front of the place - like tawdry,

street-walking versions of Zola's magnificent whore. The lucky ones might meet a john and get whisked away in a car. As I recall, the place closed

not long after I started going to the Candlelight Lounge.

The more popular place with the bar's customers was "the Greeks," a small place with a counter and booths on the northwest corner of 75th and Amsterdam. It was the stereotypical greasy spoon coffee shop staffed by a bunch of middle aged and older Greek immigrant men, and was complete with a few small icons taped to the kitchen wall. It was probably the greasiest food I've ever eaten and "breakfast" was usually two big cheeseburgers served on Kaiser rolls with a mountain of home fries and a milkshake. Delicious!

Shortly after closing a dozen to twenty or more of the bar's customers would descend on the place, overwhelming the handful of straight night owls. The head counterman was Chris, a very tall, skinny, craggy-faced older man with a loud voice and bristling manner. At this hour he usually wore an expression that looked like he was ready to bite someone's head off, and he slammed the dishes down on the table or sometimes spun them down the counter. In fact, he was a very cool number. The guys from the bar were often well oiled by this time, of course, so they were noisy, horsed around and more than one person usually managed to spill a cup of coffee or knock a plate of food on the floor. But Chris dealt with it with something roughly akin to the forbearance of a seasoned playschool teacher.

He was, however, a 100% I-do-not-take-shit-from-anyone character. The expression hadn't been coined yet, but "Chris Rules" was the name of the game. When there was bad behavior, Chris shouted at the top of his lungs and stepped in and quashed the problem. One night I saw him roar at a bunch of straight troublemakers, and then he pulled out a cleaver he kept under the counter in what was clearly a move to begin summary executions.

As the guys from the Candlelight all more or less knew each other, they didn't always keep a lid on the gay banter or sexual comments. Straight late night drinkers from the neighborhood and night shift workers who stopped in regularly pretty much ignored the gay guys and their hullabaloo. But strangers could get freaked. Unfortunately, the strangers were often groups of black guys or several black couples on their way uptown from an evening in Midtown. This, I think, exacerbated the situation tension between blacks and whites was rising in urban areas. If they started coming on with loud anti-gay remarks, then Chris would intervene and the black guys could become very threatening my take was that they deeply resented a white man coming down on them for ranking on a bunch of faggots, and saw it in terms of racism, white siding with white. And then there was Chris's manner of taking orders and serving customers, which certainly must have set any stranger on edge first thing. Fortunately, if the Greeks called the cops, the police car seemed to practically spring up out the concrete. I wouldn't be surprised if the cops were well aware of Chris's iron rule and handy cleaver (they did stop in for coffee themselves), and they probably knew if there was a call it was potentially serious.

Such, was post-bar dining elegance on the late Sixties Upper West Side. The Brasserie it was not.

During the day "the Greeks" got some of the same gay guys for customers, and though Chris could never have been called Mr. Charm, he was friendly with his gay customers from the early morning hours. (When did he sleep I used to wonder.)

ROCK AND SOUL

As the Sixties chugged toward their climax or collapse, depending upon the latest news bulletin, rock music was tilting heavily toward druggie escapism, alienation, "love," social protest and anti-war themes, all served up as pseudo-folk, acid and psychedelic rock or plain old mega-decibel stuff - packaged by Dylan (master songwriter/lousy singer/worse attitude), the Doors (featuring Jim Morrison and his big basket in tight leather pants, with occasional weenie waving at performances), Jefferson Airplane later changed to Starship - (whose entire existence could be justified by Grace Slick singing White Rabbit)...Moby Grape, Pink Floyd, the wonderful Moody Blues, Grateful Dead, et al. And in their own special categories, were the Beatles and the Stones.

WNEW-FM was the vanguard station for this music in the city, and beginning in 1966 female DJ Alison Steele - famous as the Nightbird - its high priestess.

"The

flutter of wings, the sounds of the night, the shadow across the moon,

"The

flutter of wings, the sounds of the night, the shadow across the moon,

as the Nightbird lifts her wings and soars above the earth into another

level of comprehension,

where we exist only to feel.

Come fly with me, Alison Steele, the Nightbird..."

Alison Steele, the Nightbird

The first night she was on, Steele opened with some poetry she had written, Andean indigenous music, and the Moody Blues' Nights in White Satin. "The switchboard lit up," she recalled later and from then on, while what was called "progressive" music was at its height, she ruled, but graciously. Jimmy Hendrix's song Nightbird Flying was his tribute. "I knew how to do a program that was more conceptual than anyone else." She selected her own playlist and did, indeed, have a true gift for putting together album tracks night after night into incredible listening experiences.

While WNEW had the reputation as the stations for "heads," Alison Steele had for a few years no lack of gay listeners. However, I am not aware that she ever acknowledged that even at a later point in her long career. Perhaps she never knew, or perhaps gay "heads" were no more remarkable to her than straight ones.

Barbra Streisand brought out two more albums in '66, and seemed to have the ballad singer/Broadway/TV star field to herself. She was already slotted in as the new Judy.

But the chinkachinkchinkchink rattlesnake roll of the tambourine and the punchy, driving lyrics of black music kept right on coming through. (Though certainly not on WNEW!)

Otis Redding came into his own in '65/'66 with an

incredible group of songs, among which were "Respect" and "I've Been Loving You

Too Long." He died the following year in a plane crash, age 27, otherwise

he probably would have been a major R&B/Soul star for decades to come.

Redding's recordings caught the attention of gay men, which was a

significant departure in a subculture that had traditionally prized mainly

female singers - and in days past, the weepier and torchier, the better.

But there were enough white gay men now who had taken to black urban music in

their teens that they brought about a major innovation in the musical tastes of

the gay world, one equal in its own subculture to that which occurred in the early

Fifties when white American teenagers had embraced Rhythm 'n' Blues and left the ballads and

novelty songs of the white Hit Parade behind. The world of the Sixties was

shaking -- in many ways. Despite their undoubted greatness, the likes of Judy Garland,

Sarah Vaughan and a constellation of other stars, nor the music of the New York

cabaret scene and Broadway, didn't and probably couldn't accommodate the

energy and assertiveness, the grit, joy and exuberance of current gay life.

Certainly not in New York.

Spring of 1967 Aretha Franklin's album, I Never Loved a Man the Way I Love You erupted onto the scene. A not especially noteworthy performer for Columbia, she had moved to Atlantic records, and teamed with the Muscle Shoals studios' rhythm section she unleashed a fiery, soulful sound that gave another dimension to black pop music. "Respect," (the same Otis Redding song) "Dr. Feelgood," "Do Right Woman-Do Right Man" and the title song all placed at Number One or high in the R&B and Pop Top 40 listings, as did some of the remaining cuts as well. She was a national sensation, and her music electrified gay men.

By this point, if not a couple of years earlier, gay music tastes were better gauged by the R&B chart than the pop one.

Just why is demonstrated by another powerful song from

Franklin's 1968 album, Aretha Now.

Think think think think think think

think think think think think thinkYou better think think think about what you're trying to do to me

Yeah, think

Think, think!Let your mind go, let yourself be free

[ ]

You better think think think about what you're trying to do to meYeah, think

Think, think!Let your mind go, let yourself be free

Oh freedom freedom, freedom freedom,

freedom, yeah freedom

Freedom freedom, freedom freedom,freedom, ooh freedom

(music & lyrics by Aretha)

The music starts in high gear and stays there like an excerpted run from a gospel song the instruments sustain an urgent support for Aretha's intense delivery of what is half anthem, half rebuke...an ambiguous blend of lyrics that suggest the sexual wrapped in a broader societal invocation. It's one hell of a lot grit and defiance and soaring passion packed into slightly over two minutes.

And it could be appropriated with a virtually perfect fit by gay listeners, which is why it stayed on the juke boxes of gay bars well into the Seventies.

What "Rock" and folk of almost any stripe lacked was gonads, and while gay spokesmen from the late Sixties to the Nineties have always writhed in abject discomfort at the thought, every average gay grunt on the street has always known that the root issue of their freedom is sexual. Gay liberation shares with at least one religious denomination the distinction of being a movement sprung from the human crotch, not the head. Fundamentally gay freedom is not about where you sit on the bus, or whether you can join their country club, nor is it about serving in the army, nor getting married or nor having/adopting children, or even who you love it is about that most basic and personal of human activities who you have sex with. It is about the body the visceral, the hormonal, the guts, the sweat, the smell, the feel...and those holes. All other issues proceed from this. And if it wasn't about who you want to fuck with, there wouldn't be any other questions or issues.

The industry publicity and reviews of the 2005 film, Brokeback Mountain even in gay media and discussion groups, which should know better pulled out all the stops in de-sexing the story to make the movie a het-acceptable love story. Yet, it is only because sex is initiated and continued by two men that there is a story! However, such is the fear of gay sex and the power of homophobia that the film was gelded by denial. So much for "progress" in the post-AIDS GLBT world.

Gay men in the late Sixties followed the current music that was most emphatically a musical invitation to move the body, with lyrics that entwined sex and romantic relations with freedom, release, and defiance.

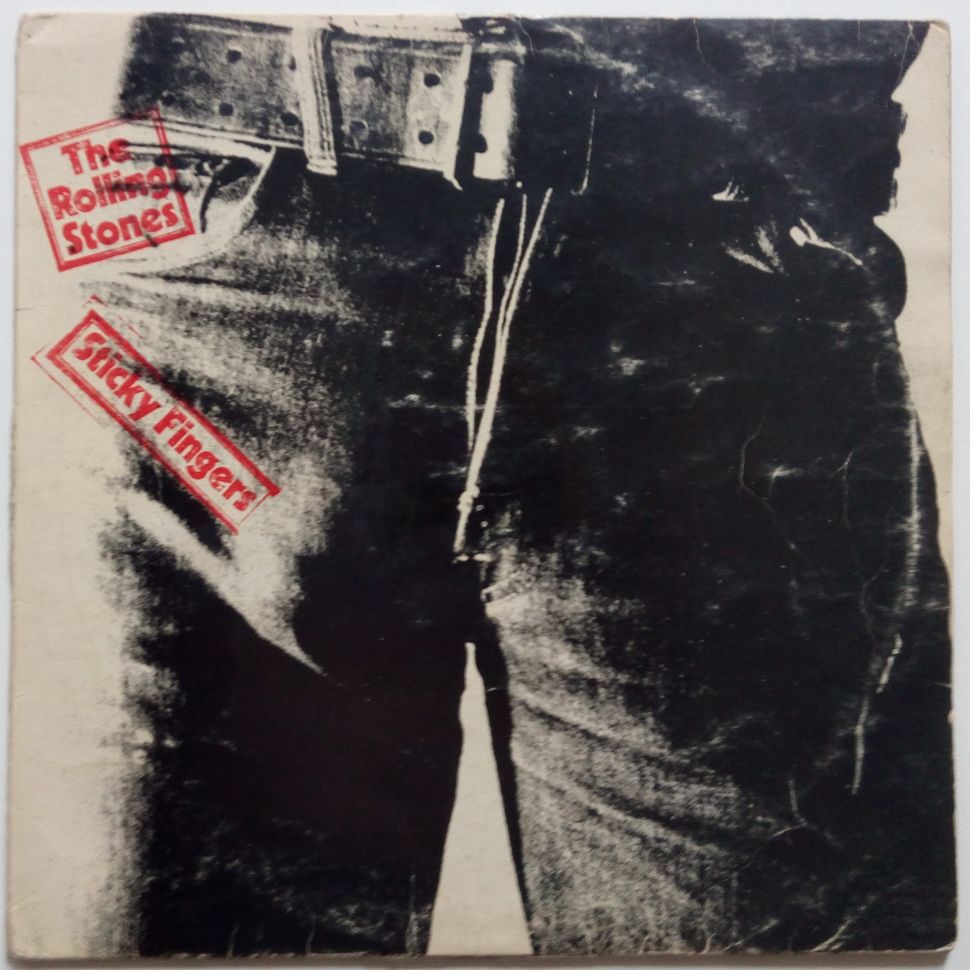

Rock Mick Jagger and the Stones' borrowings from American blacks notwithstanding did not have an ass. A gay black friend called the Stones a white minstrel show not off the mark considering that in their first three years the group used songs of black artists Muddy Waters, Chuck Berry, Willie Dixon, Howlin' Wolf, Little Richard, Robert Wilkins, Jimmy Reed, Bobby Womack, Bo Diddly, Slim Harpo and the Staple Singers. Perhaps Ike and Tina Turner had something like that in mind when one of their albums featured close-up headshots of the two of them painted in white-face makeup and chowing down on giant slices of watermelon.

I remember a ride home from the suburbs in 1968 with five other young Fairfield people packed into a company car, and getting an object lesson in the big split taking place in popular music. The Beatles had just come out with a new song, which the DJ on the car radio was repeating every five or ten minutes and each time everyone (including me) would cheer and sit there nodding their heads in time with the music, like a car full of bobble birds.

The same week one of

the big soul artists had come out with a new song maybe it was Marvin Gaye

with "I Heard It Through the Grapevine," I can't remember, or Martha and the Vandellas' "Love Bug," perhaps.

The same week one of

the big soul artists had come out with a new song maybe it was Marvin Gaye

with "I Heard It Through the Grapevine," I can't remember, or Martha and the Vandellas' "Love Bug," perhaps.

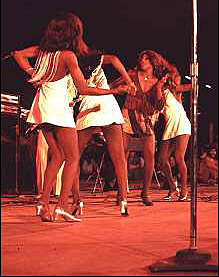

(right) Martha Reeves & the Vandellas

The DJ was repeating it too, though not nearly as frequently which put me off, but nobody else. I noticed that when it played, the others would start the head bobbin' and then fizzle out with it it just didn't go downstairs with them. Meanwhile, in a packed car I'm trying not to gyrate around too much so as to bruise the hips on either side of mine.

Straight white young people seemed to want to keep their music, literally, in the head. A little soul was cool, but they had seat belts on their asses. Yet I remember a bunch of white gay men in 1967 listening to Tina Turner's pulsating "Shake a Tail Feather," and they got out of their chairs to listen not because they thought it was the national anthem, but because you can't move your bottom half sitting down.

Rock

music might have its sex symbols, Jim Morrison and Janis Joplin, for

example, and it even managed to look like sex sometimes, though usually in the

form guitar masturbation. But no one would confuse or ever compare

Morrison and

Joplin with James Brown and Tina Turner. And no one in the next couple of years

would think that Woodstock was taking place in the same world as the Apollo Theater

or the Ike and Tina Turner

Review they weren't.

Rock

music might have its sex symbols, Jim Morrison and Janis Joplin, for

example, and it even managed to look like sex sometimes, though usually in the

form guitar masturbation. But no one would confuse or ever compare

Morrison and

Joplin with James Brown and Tina Turner. And no one in the next couple of years

would think that Woodstock was taking place in the same world as the Apollo Theater

or the Ike and Tina Turner

Review they weren't.

Tina Turner & the Ikettes (John Levy photo)

Rock did not have a bootie. Rock would never shake its groove thang.

Rock did not "get down," and Rock was not about to go near any it that was paired with get down, as in "get down on it!"

What had come to be called "soul music" was urban, gritty, defiant, full of sass, challenge and ridicule, and it was emphatically physical. It breathed hard, it growled and when it let go, it yowled.

"When I think of soul, I think of grease -----

and there ain't nothin' no good without the

greasssse!"Tina Turner, Carnegie Hall Concert

April 1971

It was ready-made for the emerging gay life. What was now called "Rock" was just on the verge of finding the center of its fan base in the young white males of the suburbs.

By the turn of the decade you could have walked into any empty bar in the Village or the Upper West Side, and just by checking the juke box known whether the place was gay or straight. I still used to go out to lunch and drinking after work with the young, straight people I worked with fairly sometimes during these years. We went to bars in the suburb where Fairfield Reading had its office, and to bars popular with young people on the Upper East Side and in the Village. In these places the amount of soul music probably never got higher than a quarter at very most, a third of the total selections, while in gay bars soul music had all but pushed rock off the juke boxes.

ALL THE NEWS IS BAD TODAY

In retrospect America in the second half of the Sixties is often is presented as something of a three-ring circus the Hippies, the racial conflict and the growing anti-Vietnam war sentiment each occupying its discrete ring in the overall razzle-dazzle. At the time, reading news magazines and the newspapers and watching television felt more like the top of your head had been taken off and someone, or something, was going at it with an egg-beater. The 6 O'clock News was like an attack of vertigo...whatever the actual significance of the events of Stonewall, it is not surprising that something, such as Gay Liberation, which began in the late Sixties, should be assumed to have started in a riot.

1967

That conglomeration of groups, gurus, ideas, music events and good times which were clumped together as "Hippie" were having some success enticing Americans into the joys of public nakedness and pre-marital sex and drugs. This looked to be culminating in the 1967 "Summer of Love" in San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury Hippie enclave; however, in distant New York it was probably just as much the cover and feature article in the very un-Hippie Time magazine that July and the opening of Hair (subtitled: The American Tribal Love/Rock Musical) at Joe Papp's Public Theater later in the year.

However, the country was not entirely all soft and runny with L-O-V-E, love.

While

the cast of Hair was practicing "Let the sun shine in...," thousands and

thousands and thousands of black Americans were screaming Burn, baby, burn!

Boston, Tampa, Buffalo, Wilmington, and more than one hundred other U.S. cities

were convulsed with rioting and arson this summer. The scale of destruction and

violence in Detroit was on a par with that of a war zone. And Ken and I could

look out the window of our apartment, and see the skies lit up with the fire of

a burning Newark just across the Hudson that city was declared to be in "open

rebellion." Federal troops entered Newark and Detroit to suppress the uprisings

there. The extent of death, injuries, property destruction and financial loss

across the nation had not been this great since the Civil War. The cost in

intangible terms was probably greater.

While

the cast of Hair was practicing "Let the sun shine in...," thousands and

thousands and thousands of black Americans were screaming Burn, baby, burn!

Boston, Tampa, Buffalo, Wilmington, and more than one hundred other U.S. cities

were convulsed with rioting and arson this summer. The scale of destruction and

violence in Detroit was on a par with that of a war zone. And Ken and I could

look out the window of our apartment, and see the skies lit up with the fire of

a burning Newark just across the Hudson that city was declared to be in "open

rebellion." Federal troops entered Newark and Detroit to suppress the uprisings

there. The extent of death, injuries, property destruction and financial loss

across the nation had not been this great since the Civil War. The cost in

intangible terms was probably greater.

The country was emotionally in turmoil and exhausted, and glad when winter approached. Had we only known what was ahead the entire nation would have stayed in bed with its head under the covers for the entire next year.

1968

In January, during a holiday truce, the Communist forces in Vietnam launched a major surprise offensive against American and South Vietnamese forces on the eve of the Tet (lunar New Year) celebrations. Provincial capitals throughout the country were seized, garrisons simultaneously attacked and, perhaps most shockingly, in Saigon the U.S. Embassy was invaded.

Tet clearly demonstrated that the optimistic statements U.S. spokesmen had been making about Communist weakness were a bunch of crap measured against the strength the Communists had shown in this battle. When the same spokesmen said after the Tet Offensive that the Communists had been badly weakened, they were telling the truth for a change, but they had a lot of trouble persuading now anyone to believe them. When General Westmoreland, the US commander in Vietnam, asked for 200,000 more American soldiers for Vietnam, this made people even less willing to believe that the Tet Offensive had been a brilliant American victory.

The cost in North Vietnamese casualties was tremendous but the gambit produced a pivotal media disaster for the White House and the presidency of Lyndon Johnson. The strategy toppled the American president. It turned the tide of the war.

It was unbelievable when on April 4th news

bulletins announced that Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. had been shot by an

assassin in Memphis then that he was dead. It was as gut wrenching as the

assassination of JFK, but the follow-up to the president's death had been a

period of national unity in mourning.

It was unbelievable when on April 4th news

bulletins announced that Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. had been shot by an

assassin in Memphis then that he was dead. It was as gut wrenching as the

assassination of JFK, but the follow-up to the president's death had been a

period of national unity in mourning.

Washington, DC 1968

The aftermath of the King assassination began immediately in an outpouring of Afro-American fury and sorrow that set Detroit ablaze again and Boston, Chicago and over one hundred more towns and cities. In Washington, the nation's capital, troops protected public buildings as fire destroyed block after block of the city. The White House was guarded by the army and at one point rioters were within two blocks of it. A pall of smoke hung over familiar national monuments.

The racial divisions in America were a bleeding wound again.

AND IN "FUN CITY"

Leaving my building on February 3rd of that year I had seen (and smelled) an omen of what the year held in store all along West 72nd Street on my way to the subway. The Lindsay administration and New Yorkers were feeling the effects of yet another strike. This time it was sanitation workers, which meant that the first layer of what were to become ten-foot high mountains of garbage in some places were already accumulating and would continue to accumulate at the rate of 10,000 tons per day. Thank God! it was still relatively cold out, because by the end of strike, seven or eight days, the mess was grotesque and the rats increasingly fearless.

March 22nd brought the Yippies' "spring equinox celebration" to Grand Central Station. (The Yippies could be roughly characterized as Hippie-like political provocateurs and showmen.) Five thousand showed up to disrupt the place, and there was a riotous confrontation with the NYCPD. Normally I would have been commuting through Grand Central, but that Friday I got a ride to and from work.

Lindsay and New York did better briefly at the time of Dr. King's murder in April.

John Lindsay displayed an enormous courage and empathy that saved the city from widespread violence. In the past he walked the streets of Harlem and Bedford-Stuyvesant when the police were sure riots would break out. He stood eye-to-eye, without bodyguards, on hot nights, with very angry people and calmed them down. And the city didnt burn then. John Lindsay walked into Harlem again, on this worst of all days and the enraged black populace held back again.

In a time of national calamity, as many, many other urban centers were contemplating acres of smoldering ruins, Lindsay really looked every inch a hero to New Yorkers.

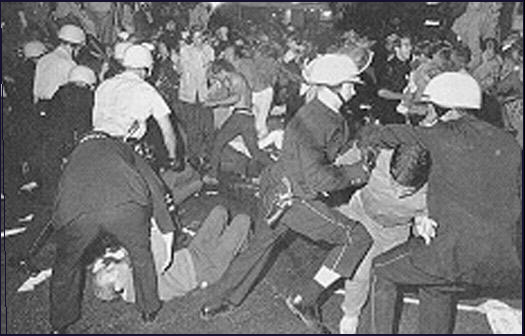

About

three weeks later, on April 23th, Columbia University student protestors seized

one building, more buildings were occupied in the following days.

The protest

ostensibly began over the administration's proposal to build a University

gymnasium by clearing nearby black housing, but in an era of protest

and

defiance demonstrations had become a collegiate entertainment as well. On April

30th the college administration decided it was not amused and called in the

police, who dragged students out of the buildings, beating some who are only

passively resisting.

and

defiance demonstrations had become a collegiate entertainment as well. On April

30th the college administration decided it was not amused and called in the

police, who dragged students out of the buildings, beating some who are only

passively resisting.

Police attacking students at Columbia U.

Mounted cops charged through campus striking out at any student in their way. Game time was definitely over. Many faculty were shocked, next day the campus was closed by a strike. It was a debacle in which both students and administration were tarred, but it also drew strong criticism onto the police, whose actions were seen as far too similar to those used by police in the South to beat down black civil rights demonstrators.

The Hippies were becoming the country's security blanket. No matter how you felt about them, their doings as presented in the print media and on TV provided sweet relief from racial warfare, burning cities, war protests and the Vietnam War itself. In fact, letters to the editor suggested that the media might even purposely be giving the Hippies too much publicity in an effort to distract the nation from the tidal wave of discontent. I believed it was quite possible. Some professional commentators wondered the same in magazines articles. And New York was about to enjoy a big swig of this soporific.

Hair re-opened on Broadway on April 29th at the Biltmore Theater, only a few days after the Columbia riots. (It ran from April 29, 1968 to July 1, 1972, closing after 1,742 performances.) It sang of sex and dope, black and white and, in a brief little musical package:

Sodomy...

Fellatio...Cunnilingus...Pederasty.Father, why do these words sound so nasty?Masturbationcan be funJoin the holy orgyKama SutraEveryone!!photo: Barry McGuire lead, and two other cast members