When My World Was Young 1945-56 The Yellow Brick Road 1956-60 What a Wonderful Town 1960-61

Wonderful Town (pt. II) 1962-66 The Gay Sixties 1966-70

The Juicy Life 1971-76

Juicy Life (pt. II) 1976-80

Losing Alexandria 1981-87

The AIDS Spectacle

Losing Alexandria (pt. II) 1987-1990's

Personal Epilogue

CONTINUATION:

Part II of Losing Alexandria

(1987-1990's)

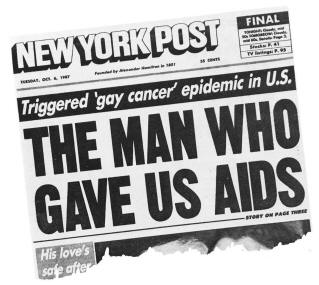

Front page of NY Post Oct. 6, 1987

THE MAN WHO NEVER WAS: THE MYTH OF "PATIENT ZERO"

There was a growing climate of fear and hatred across the United States born of ignorance and government lethargy, and it was eagerly fanned into hysteria by hate mongering political and religious conservatives and extremists in no small supply, then as now, in the U.S. population. The wildest exaggerations and lies were circulated concerning the ease of HIV transmission, draconian measures were called for against gay men, infected persons should be quarantined or tattooed or both, infected children were thrown out of school and their homes attacked, funeral homes refused to take the bodies of deceased persons who had died of AIDS or demanded exorbitant fees and on and on and on it went wherever one turned and the mills of hatred, financed largely by the followers of evangelical Christian groups, disseminated an endless virulent spew of distortion and lies in the media and on the Internet. [Yes, there was already an internet in these years with a thriving series of news groups.] However, the Roman Catholic hierarchy's pronouncements on the topic were usually intolerant, as well as systematically obstructive toward measures promoting HIV infection prevention. And this negativity encouraged Catholic laypeople in behaviours virtually as hostile and ignorant as those of evangelicals.

The Reagan administration's official distaste for the topic of the AIDS epidemic and the timorous attitude of mainstream denominations of the Protestant majority, meant that hatred of HIV-infected people and of all gay men swept the United States. The mainstream AmericanProtestants, like the "Good Germans" of the 1930's, chose not to see the abuse being visited upon persons an unpopular minority. And the Reagan administration disdained to take a leadship role for fear of antagonizing the conservative Christians who had become part of its core support.

The nation boiled with fear, misinformation and hate.

Into this climate was born a beast more terrifying than Bram Stoker's invention of Dracula, with the publication of Randy Shilts' And the Band Played On in 1987. Shilts gave a name to "Patient Zero," the supposed central patient in the HIV crisis indeed, perhaps the first or index case in the epidemic it was claimed. He was Gaetan Dugas the world was told, a French-Canadian airline flight attendant, and he was a monster: Dugas was diagnosed in 1980 with "gay cancer," and had been charming but uncooperative with medical authorities, and he had then crisscrossed the United States with a fiendish mission to infect as many men as he could.

This

demon Shilts crafted had died in 1984...which conveniently allowed for no direct refutation of the

book's scenario.

This

demon Shilts crafted had died in 1984...which conveniently allowed for no direct refutation of the

book's scenario.

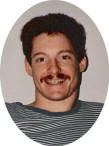

(right) Gaetan Dugas

If the media became obsessed with Shilts' "Patient Zero" Gaetan Dugas the gay man who brought the AIDS virus from Paris and ignited the epidemic in North America, and then went on a killing spree before he died the hate mongers embraced him with the wild enthusiasm they usually reserved for the Anti-Christ or Communism. Here was all the "proof" anyone would need to accept their most extreme attacks on gay men. The hatred was volcanic now, and then too, "Patient Zero" was a great moneymaker all around St. Martin's Press, Shilts' publisher, pumped up sales by emphasizing the shock value of "Patient Zero."

A large ad ran in the August 23, 1988 New York Times and in the leading advertising industry trade paper, Ad Week promoting California Magazine's publication of an excerpt from Shilts' And the Band Played On," dealing with Gaetan Dugas, "Patient Zero." Illustrated with a photo of Dugas, their ad claimed, "The AIDS Epidemic was not spread in America by a virus. It was spread by a single man." The magazine crowed, "While everyone was searching for a cure for AIDS, we found the cause." It also credited Dugas with infecting "up to 250 men a year."

None of these statements were true.

Gaetan Dugas was not "Patient Zero." There was no "Patient Zero."

In 1984 Drs. William Darrow and David Auerbach Centers for Disease Control (CDC) published the results of a study they had conducted in The American Journal of Medicine. This epidemiological study from San Francisco purportedly showed how 'Patient O' ("oh," the letter, for "Out of California") had given HIV to multiple partners, who in turn transmitted it to others and rapidly spread the virus (Auerbach, Darrow et al in The American Journal of Medicine, No. 76, 1984, pp. 487492). At least 40 people of the 248 diagnosed with AIDS by April 1982 were thought to have had sex with him or with someone who had. The article did not claim that Gaetan Dugas was its source in the U.S., and, in fact, it did not even use his name. The press mistakenly interpreted the designation as Patient 0 (i.e. zero) rather than O. Shilts used this information, naming Gaetan Dugas, as the basis of his sensational creation in ATBPO, though Dr. Darrow asked him not to identify the man by name. Evidence for Gaetan Dugas' career as a premeditated killer intentionally infecting other men - which is how Shilts painted the man - was never produced by the author.

Follow-up re-examination of the clinical data by Dr. Andrew Moss, Dept. of Epidemiology and International Health of the Univ. of California, a few years later showed that some of the data had been misinterpreted and much of it was partial. It was virtually impossible for Dugas to have been the core infected individual of the forty-couple cluster at the center of the study.

The belief at the time the data for the study had been gathered was that the period from infection to the manifestation of the disease was one year. And on the basis of that belief the cluster was constructed which had Gaetan Dugas as its center. But an incubation period of less than two years for the manifestation of AIDS was, in fact, known to be rare by 1987. None of those for whom data were given in the study could have been infected by Dugas, and there was no grounds for assuming that those for whom no data was presented had been infected by him either. These facts were available to Shilts as he was finishing his book, but he did not revise his original scenario in light of them.

In addition, an article in the Journal of the American Medical Association in 1986 reported that in 1980 over twenty percent of the Manhattan gay men in a Hepatitis-B experiment were HIV-positive. This 20% infection rate was discovered after the HIV blood test became available in 1985, and after the stored blood at the New York Blood Center was retested for HIV antibodies. Clearly, the retrovirus was already well established in New York by 1980. This was published in the year before Shilts brought out his book, and it totally blew the theorgy of Gaetan Dugas as "Patient Zero" out of the water. HIV infected men existed in the New York City gay population by the hundreds (at least) in 1980. But Shilts, a lay expert supposedly up to his ears in the latest AIDS research, was clearly more concerned with preserving the drama of the evil demon he had built into his book around than he was in accuracy.

A 1983 study of about half of the first five hundred cases among San Francisco men had produced the fact that about one-third of them had had sex in New York City in the late 70's. Any one of them, or many of a number of them, could have brought the disease to their city. Another debunking of "Patient Zero."

As for Gaetan Dugas, the sociopathic man intent on what amounted to a murder rampage as depicted by Shilts, Dr. William Darrow, who conducted the study upon which Shilts based his character and characterization, found a very different person than the man encountered in the Shilts' book. According to Darrow, "He [Dugas] felt terrible about having made other people sick. He had come down with Kaposi's sarcoma, but no one ever told him it might be infectious. Even at the CDC we didn't know that it was contagious." [Emphasis added.]

Like myself, and millions millions of other people, Dugas had been educated to understand that cancer is not contagious.

Dr. Moss pointed this out when he said, "It is a general dogma that cancer is not transmissible. Of course we now [emphasis added] know that the underlying immune-system deficiency that allows the cancer to grow is most likely transmissible." One needs to remember that Dugas died in 1984, and the discovery of the HIV retrovirus was not announced until April of that year. He hadn't a clue, any more than I or any other person outside of those doing the research.

Gaetan Dugas's panel from the Canadian AIDS quilt, he also has a panel in the U.S. quilt.

Shilts'

book ignited a wildfire of hatred, but neither he nor his publisher repudiated

the "Patient Zero" label assigned to Dugas in light of the clinical evidence or historical facts

that had been available before its publication. St.

Martin's Press continued to capitalize on the Gaetan Dugas furor to promote the book.

Shilts'

book ignited a wildfire of hatred, but neither he nor his publisher repudiated

the "Patient Zero" label assigned to Dugas in light of the clinical evidence or historical facts

that had been available before its publication. St.

Martin's Press continued to capitalize on the Gaetan Dugas furor to promote the book.

Shilts was lauded by reviewers at the time, and religious conservatives and hate-mongers adored him, here was the good homosexual giving the lowdown on the tribe of bad gays who had wilfully caused this horrible plague.

No gay person caused more harm to gay men with AIDS, and to gay men in general during these years than Randy Shilts.

He did not, of course, make his own activities in San Francisco's baths and sex clubs a part of his book. And Shilts despite being a gay man, and one infected with HIV, though he kept this latter fact private for some time never made a high profile statement in an effort to put a halt to the horrific train of damage he had set in motion, nor did his publisher. He, thus, remained Mr. Squeaky Clean investigating gay reporter, in a world of depraved "gay clones." And, thus, Randy Shilts kept his own very profitable band playing on. Shilts did not die until early 1994, by which time all of the above information had been available to him for years. But he never repudiated nor apologized for using already dubious data when finishing off his fictional creation of Gaetan Dugas as the monster "Patient Zero." Nor did he ever repudiate the savage unattributed remarks in his book that Dugas was supposed to have made to his "victims." And ATBPO never got the major revisions in subsequent editions which the truth demanded; thus it lives on spreading its misinformation and outright lies, and still generating hatred and shame.

However, as long as that band played on its author was an AIDS celebrity and he and his publisher made a ton of bucks, so why give a rat's ass about anyone else?

During the late Eighties, when the negative impact of the Shilts' book was at its height, I was working as a volunteer with PWA clients of GMHC, taking care of three friends while they died, and spending enormous amounts of time in hospitals and in AIDS-related activities, including the Usenet newsgroup sci.med.aids. In those years it was not unusual in any of these situations to be faced with Shilts' "Patient Zero" several times a week. If the Beatles had been better known than Jesus in the Sixties, as they once claimed, then the fiendish "Patient Zero" was better known than the Devil in the final years of the Eighties. Even at work, I had well-disposed but upset straight people quietly bring up this monster for discussion. The Shilts' portrait of the non-existent "Patient Zero" was a curse that dogged gay men for years.

In calmer times ATBPO would be reappraised, and Shilts would be

criticized sometimes deserved harshness for omissions, slanted writing, invented conversations, and

the factual errors (and omissions) in the book. But the damage had been done, and Shilts himself

was now deceased. To this day, however, his portrait of "Patient Zero" is quoted as

fact across the Web and is a standard weapon in the Religious Right hate arsenal...and

is even received knowledge among younger gay generations. Shilts was a

opportunist author, and the impact of his book was horrendous.

Randy Shilts' AIDS quilt

panel

himself

was now deceased. To this day, however, his portrait of "Patient Zero" is quoted as

fact across the Web and is a standard weapon in the Religious Right hate arsenal...and

is even received knowledge among younger gay generations. Shilts was a

opportunist author, and the impact of his book was horrendous.

Randy Shilts' AIDS quilt

panel

In 2016, almost three decades later, the public got a final wrap-up on the non-existent "Patient Zero." October 6, 2016 the BBC featured a story "HIV Patient Zero Cleared by Science." The New York Times followed on October 26, 2016 with a story, "HIV Arrived in the U.S. Long Before 'Patient Zero'," and on November 29, 2016 with more coverage, "The Ethics of Hunting Down 'Patient Zero'."

There is savage irony in the fact that the Publishing Triangle presents an annual "Randy Shilts Award" to honor outstanding books of non-fiction relevant to the LGBT community. If that isn't totally inappropriate and puke-inducing, what is? The man was an opportunist, his book larded with fiction.

At the turn of Fortune's wheel, one is deposed,

another lifted on high to enjoy a short exaltation.

Fortuna Imperatrix Mundi,

Carmina Burana

THE WHEEL OF FORTUNE

Although I had resigned from an active role in my CIW team at GMHC when Chuck's illness reached crisis proportions, I remained as team secretary. After the death of John, my first client, I had also trained to do clinical intakes of new clients the number of people looking for services had become like a tidal wave. The numbers were so great that limits had to be set on the number of new people that could be seen each week. Almost everyone who called GMHC for help got an in-depth intake interview, which was intended to allow the person to talk about his needs and consider possible future situations, and for the interviewer to explore how GMHC might be of help. These were usually done at GMHC's new quarters on several floors above a bar on the corner of West 19th and Eighth Ave, or if necessary at the person's home or in the hospital. I continued to do these regularly until 1995. During those years I met with gay men, of course, but also lesbians, straight drug users, drag queens, women who had been infected by their husbands, and even a blood-drinker (I swear this is true).

When doing volunteer work as a CIW or CMP I was sometimes bothered by feelings that things were not going well that somehow I wasn't making the right connections. But the intake interviews were something that I just seemed to have a knack for. They were the best work I ever did for PWA clients at GMHC, and the most consistently good work I ever did in my life. I still have vivid memories of some of those many people. And even now, more than two and a half decades later or more, some of these people appear in my dreams once in awhile. I can remember times at the end of a three hour "interview" conversation when the client and I stood up and put our arms around each other as we said good-bye moved, emotionally exhausted, sad and happy both feeling that something good had happened. And this was not an experience limited just to the gay interviewees.

Doing intakes meant that I was at the GMHC offices more often than in the past, and I got to know some of the staff members in Client Services better. Bob Cecchi (who was now the clients' Ombudsman at GMHC) and Gino both worked in the administration and through them I met more GMHC staff and volunteer team leaders. So, while I had experienced the changes at GMHC in these years from the viewpoint of a volunteer on a team a position at quite a distance from the formal administration, of course now I was aware of the concerns and feelings of the men and women on the staff who were closer to the personal conflicts and organizational upheavals at GMHC in those years.

Just how badly some GMHC departments needed to be overhauled was tragically illustrated by something that happened on our team during 1987. One of the CIW buddies had as a client, Sam, an immigrant to the U.S. who had had a series of low paying jobs, and had no insurance nor savings. He was referred to the Financial Department, whose job it was to analyze what benefits a client might be eligible for ( e.g. Social Security Disability, Medicare, Medicaid, NYC welfare, etc.) and to prepare the complicated application forms, check to be sure any required backup was included, and then send the application package to the proper agency and follow up if problems developed. It was the most utilized service that GMHC provided as persons with AIDS were often quickly pauperized by the cost of medications and hospitalizations.

Problems were being encountered more and more often in

dealing with GMHC headquarters as the number of people seeking services

increased. However, the Financial

department had become notorious among volunteers and clients for foul ups.

Problems were being encountered more and more often in

dealing with GMHC headquarters as the number of people seeking services

increased. However, the Financial

department had become notorious among volunteers and clients for foul ups.

Sam had completed his paperwork and left it with the Financial department. He heard nothing from any government agencies, but inquiries with Financial produced reassurances that things had been taken care of, help was on the way. Sam's lover, fortunately, had a good job and savings and he began footing Sam's increasing frequent medical bills. There were more inquiries, and more reassurances from GMHC Financial. Sam had more serious complications, requiring more medications and hospitalizations. Months had gone by, the inquiries from Sam and his CIW got more frequent and more insistent. Sam became sicker, the CIW and the team leader appealed to the Financial department head. The problems weren't with GMHC she assured them. The costs to Sam's lover had become staggering, he and Sam were torn with anxiety about their financial situation, in addition to worry over Sam's increasingly poor health. Sam died. It was over a year after he had gone to GMHC for assistance in getting his financial entitlements. Sam, his CIW and the CIW team had received a stream of reassurances from GMHC's Financial department, and they had meant nothing. The team felt humiliated and betrayed.

Our team leaders complained, and Sam's lover sought legal advice. And then it became apparent that yet another client assigned to the team was encountering similar problems and he had the same financial advisor in the department as Sam had had. Stories began surfacing about other problems with this same person.

The members of our team decided that only a desperate act of brinksmanship would bring the situation to a head. They agreed that as each team member's client died, moved or for whatever reason was no longer assigned to the team, that volunteer would decline to take another client. The time would come, of course, when none of the team members would have a client, and at that point the team would resign from GMHC as a group, citing the crumbling level of service. (It is worth emphasizing that this was not a group of hot-head "kids going off half-cocked," but adult men and women who were deeply, even passionately, devoted to GMHC and their work as volunteers.) At the next team leaders' meeting at GHMC headquarters our team leaders informed their peers and the GMHC administrators who ran the meetings of our decision.

Nothing like this had ever happened before and coming as the epidemic was cresting it was a sure sign that the honeymoon was over.

There was some very fast footwork the head of Financial was

shunted to another post and immediately replaced on an interim basis by another

staff membe; the financial advisor in question was fired. Our team was

informed that he had had eighty complaints lodged against him during his first

six months on the job, and

yet

the former supervisor had protected him. Furthermore,

in his work space were found many financial application packages that he had

never completed and sent out, and unresolved problems just shoved aside.

yet

the former supervisor had protected him. Furthermore,

in his work space were found many financial application packages that he had

never completed and sent out, and unresolved problems just shoved aside.

The new broom swept furiously and well. Over time a relatively short time considering the backlog and problems the new supervisor had things running far more efficiently.

I have no recollection now of hearing what Richard Dunne's reaction was to this the extreme level of incompetence and ass-covering on one hand, and the active and dangerous (in regard to bad publicity) loss of confidence on the part of an entire volunteer team. But it could only have spurred him on, I assume. He had already embarked on a campaign to "professionalize" GMHC. He created a bureaucratic structure staffed with credentialed recruits that replaced the existing grassroots gay leadership at GMHC, though unfortunately this began to isolate the GMHC administration from those they represented as well as from many of its volunteers.

Under Dunne's direction GMHC seemed strangely insensitive to the fact that events within the organization reverberated through the morale of the gay male population of the city. Staff and volunteers certainly talked to their friends about what was happening at GMHC, and I remember that PWA clients of GMHC were very vocal about their experiences. Their news and opinions spread through the gay male population of the city to a surprising degree. Somehow in my estimation there was a puzzling failure to appreciate that many gay men had a very emotional attachment to GMHC. It was their hope, it might even be their salvation and at the very least it was a kind of psychological touchstone in frightening times.

Three specific occurrences, which I wrote down in a journal, aroused concern from friends or acquaintances outside the circle of the formal GMHC organization.

The first concerned Diego Lopez, who was the Clinical Director, or perhaps he was called Director of Client Services. In any case, he was a Vietnam vet and had been one of GMHC's earliest volunteers. He conducted part of the training session which I took part in and it has been my understanding that he designed the training program, which became a model for other AIDS organizations. Diego was certainly at this time one of the more recognizable names/faces of GMHC.

I'd met Diego socially through my friend Bob Cecchi. The last time was in the Pines in '85, as I recall. I found him to be a very self-confident guy with a lot of energy and a sometimes overwhelming sense of humor. He made a strong positive impression on me at the training, and Bob said that Diego was deeply committed to the issues that affected the clients. I also heard from a couple of people that he and Richard Dunne were often at loggerheads, and that Diego was inclined to stick to his guns where the clients were concerned and not defer to Dunne.

Diego became ill with AIDS. The next thing I heard was really shocking news, which came from several staff members. Diego had been hospitalized, and when he returned to work he found that his things had been moved out of his office. It was not long after that he was out of GMHC. The interpretation that I got was consistent no matter who did the telling, and it was that he was being given the message that it was time to leave whether he thought so or not.

The story that traveled on the grapevine was terse and ugly: Diego was a longtime GMHC member who was sticking up for the clients. Dunne was a ruthless "outsider." He used Diego's illness to get him out of the way. (Many people seemed to know of Richard Dunne only as someone who came to GMHC from city government, and had forgotten or were unaware of his long association with GMHC.) A gay neighbor from down the street, David, who knew I volunteered at GMHC, asked me if it was true what happened to Diego, and he repeated the story. I was dumbfounded that it had come through the grapevine to David, and not from someone who was in the administration of GMHC. The effect of the story, whenever it surfaced, was poisonous. Diego died in late September 1986.

I would have rather believed that perhaps Diego really had not been physically or mentally capable of doing his job as a result of his illness, and had been eased out for those reasons. However, a couple of years later something happened which supported the assertion that ill-will had motivated Diego's ouster.

Someone who admired Diego's work and commitment asked Van Riblett, a professional artist to do a painting to memorialize him, which he would then donate to GMHC. (I knew the artist at the time, and saw the painting as it progressed.) Instead of doing the usual portrait, the artist painted a still life of objects, each one representing a segment of GMHC's client population gays, women, blacks, etc. Among the objects was painted a framed photo of Diego. The finished work was beautifully executed, and a tribute to the PWA clients of GMHC as well as Diego. The organization was notified of the intended gift and asked to come and see it. However, no one ever contacted the artist. More calls were made over months; finally someone did appear, who allowed as how the painting was indeed very nice. GMHC would be back in touch to arrange for receiving it. That never happened.

The painting was finally offered to Bailey House, which graciously took it. Perhaps it may still be there. I would like to think that Diego is still being appreciated, even if only passively by a painting hanging on a wall in Bailey-Holt House on Christopher Street.

The "professionalizing" of the GMHC staff was a more complex affair of re-organization. Ostensibly the goal was to fill positions which became vacant and new positions with individuals with credentials from the fields of social work, health, psychology, etc. There were two unpleasant hitches in this process which caused demoralization among many of the staff. I was volunteering at the time, and I knew people who were full-time staff members, and in my opinion the criticisms were totally justified.

First, was the issue of what is usually called "grandfathering." What this term means is that existing personnel/practitioners are excepted from the impact of changes in rules and requirements that would otherwise prevent them from advancing at work or practicing in a field of endeavor in which they were already active. As far as I heard, nothing was articulated about this when Dunne's goal of "professionalizing" was announced. And I can clearly recall the profound negative effect this had on many staff members who did not have the degree requirements or previous experience in social work, psychology but had been serving effectively at GMHC for years. As one employee put it when I bumped into him at a coffee shop, they were going to end up being "squeezed out." Another staff member sitting beside him said, "A polite way of saying dumped."

Second, some of the initial new hires in this drive to "professionalize" looked to be far less qualified than staff members who were passed over. Several, while having the desired academic credentials, had had only one or two post-college jobs and these did not involve AIDS. They would for all intents and purposes be performing at a trainee level while in positions superior to the proven veteran employees who were passed over. Three of these (now "not qualified") veteran staff members that I can recall found positions with other organizations or hospitals and left GMHC taking their first generation experience and spirit away from the organization, and creating a sense of loss and uneasiness among the volunteers who had known and worked with them.

How much unpleasant stories filtering out from the ranks of GMHC staff and volunteers disturbed the general gay male public I cannot gauge. But in regard to each of the incidents cited above I did have gay men who knew I volunteered at GMHC ask me about them. However, there was one event which did have an unequivocal highly negative impact on gay men.

GMHC had donation cans in every gay bar in town, I think. And these cans if Boot Hill and other Upper West Side gay bars are indicative were an emblematic connection many gay men had with the organization. Maybe you knew someone who used GMHC's services, maybe you knew a volunteer, maybe you read something about it in the Native - maybe - but nobody could miss the collection cans. The collection cans stood for GMHC, they were in an actual sense, I think GMHC sign posts in the neighborhood.

How much money was collected from this source I have no idea, certainly not enough to fund the organization by any means. And the job of collecting the cans and counting the money must have been labor intensive, even with coin counting machines. These statements are just conjecture on my part, but they might explain why the new GMHC with the growing demands on it for services decided to do away with them.

Whatever the case, one day they were gone. "Where's the GMHC donation can?" was asked over and over again. There was no official GMHC explanation offered at the bar level that I ever heard about. The bartenders were left to parry with some very surprised men. I remember the disbelief, and then the resentment and hurt. It was like a light went out. "They took them away!" And GMHC headquarters as some remote They was a gauge of gay men's feelings of betrayal. In our neighborhood, which for a time had the second highest rate of AIDS in Manhattan, this was an ugly slap in the face. "What's the matter, didn't we give enough" In a real visual sense GMHC had withdrawn from the neighborhood. Now it was "me" and "us" - and somewhere downtown a "them." The stupidity of not at least posting official notices in the bars thanking people for contributing was grossly ignorant and ungrateful.

The feeling tone (and the illusions) in everyday gay male life which had grown since the early days of the epidemic were running head on into the reality of mainstream demands for formalism and hierarchy and the need for Big Bucks. The people who had founded, volunteered and staffed GMHC in its first half dozen years were disappearing at the same time. Organizational needs and deaths were producing a new GMHC.

Regrettably, it was and remains my impression, that Richard Dunne never seemed to sense, or maybe didn't wish to address, the disillusion developing at the grassroots level. Dunne without a doubt increased the efficiency of the organization in the face of the rapidly growing epidemic, but the manner in which changes were effected showed an incredible lack of understanding of the gay male community and its supporters and how much the grassroots origins of the organization mattered to it. Unfortunately his previous career in the NYC government while it may have honed his administrative skills, seems to have also inclined him to a bureaucratic aloofness

In the closing years of the '80s there was a growing sense

of disaffection among those![]()

volunteers who were paired with PWA's. And this was

communicated to the organization, I know, by the network of team leaders.

The

"us" and "them" perception in regard to the GMHC headquarters was most

pronounced among those men

and women who had been volunteering since the

mid-Eighties or earlier, than among those who had joined and trained under the

changed organization. Gino made the remark, "Next they'll take the G out

of GMHC." I thought the comment was his, but I soon

heard those same words expressed off and on by many people in the closing years of the

decade. On the other hand, the organization was gaining support from

outside the gay community. It was around 1987 that real estate mogul,

Donald Trump, donated $25,000.

volunteers who were paired with PWA's. And this was

communicated to the organization, I know, by the network of team leaders.

The

"us" and "them" perception in regard to the GMHC headquarters was most

pronounced among those men

and women who had been volunteering since the

mid-Eighties or earlier, than among those who had joined and trained under the

changed organization. Gino made the remark, "Next they'll take the G out

of GMHC." I thought the comment was his, but I soon

heard those same words expressed off and on by many people in the closing years of the

decade. On the other hand, the organization was gaining support from

outside the gay community. It was around 1987 that real estate mogul,

Donald Trump, donated $25,000.

But in one of our team meetings at a low point in August '87, a

volunteer had declared, "We dont need them for anything but client referrals!"

And his remark was well received. It was a hyperbolic assertion, of course the

one-on-one volunteers did need the GMHC headquarters for more than being

assigned to client PWA's and then going on their own way with them. Without the resources

of 20th Street volunteers would have wasted a great deal of time

hunting for the information and leads which allowed them to help their clients

resolve a multitude of problems. Nevertheless, the PWA client's primary bond

with GMHC was the relationship with their own personal, and for longtime

volunteers, at

least, the relationship with the client was more meaningful than their

identification with the organization. And it was not unusual, in my

observation, for the PWA-volunteer pair to share a latent or

low-keyed adversarial perception of GMHC headquarters. The view on the volunteer

teams that they were semi-autonomous islands was pervasive by this time in my

observation, and expressed in exactly that geographical metaphor.

1987: AIDS MOMENTS

Five hundred thousand people marched in Washington, DC for gay rights. Black actress Whoopi Goldberg referred to Ronald Reagan as "the fucking president" in a speech criticizing the administration's slow response to the epidemic.

The AIDS Memorial Quilt was displayed for the first time and it covered an area the size of two football fields. If ever displayed in its entirety again, the quilt would stretch from the Capitol, past the Washington Monument, to the Lincoln Memorial.

Senator Jesse Helms, in presenting his amendment to curtail AIDS funding that presented homosexuality positively, referred to the civil rights demonstration as a "mob" and a "disheartening spectacle." He firmly believed that AIDS was divine punishment for homosexuality, and he bitterly opposed Federal funding for AIDS research or treatment.

In 1987 there were 29,105 new cases of AIDS in the U.S., and 16,488 deaths. Almost half still in New York and San Francisco.

It is undeniable that GMHC's overall efficiency had improved under Richard Dunne's administration after its early slump, but at the price of an atmosphere of increasing formality and distance, which became substantial after the organization moved to slick new quarters in 1988 in a six-story building on West 20th Street. The sense of GMHC as a place mutated into GMHC as a space. Anyone who remembered the reception room on 19th Street - and William who worked the desk - knew when they encountered the reception area on 20th Street with its grey industrial carpeting and a receptionist behind a formidable counter that it was a whole new ball game.

West 20th Street building.

West 20th Street building.

A new atmosphere of carping and disappointment was often in evidence at 20th street. Some staff members derisively accused others of using GMHC as a rung on their "career ladder." Standing talking to someone in the Client Services area and looking over a roomful of cubicles each with its occupant bent over a desk, it was a clone of the university computer center where I worked. And the cynicism in the air was familiar. I had been surprised, sometimes even shocked, in my early days working at the CUNY Central Office at how prevalent pettiness and feuding were at all levels there. It seemed a long way from its lofty ideal: Education. However, it was a part of it, and what I had in mind as Education still did occur on the campuses and in the classrooms, despite what I saw at the Central Office. (Perhaps it doesn't need saying, but for someone who had been "around the block" in the NYC work world more than a few times, I was still sometimes inexplicably naive in my expectations of people and institutions.)

In 1989 I wrote after a visit to 20th St. to do an intake

interview: "See and hear too much

when hanging around 20th Street. Must disengage myself from that kind

of contact and stick to doing intakes and leaving. I have reached the point

of wanting to know nothing of what is going on there."

GMHC headquarters had taken on the appearance of the classic white collar factory. But changes had been inevitable and necessary, and there is a virtual certainty in the growth of organizations which includes the development of a from-the-top-down attitude and an increasingly ham-fisted management style. And, yet, the volunteer teams managed at the same time, even if very stressed by these changes, to maintain and communicate the spirit of personal compassion, of people caring for and about people. This experience was parallel to that which I saw in the CUNY Central Office as compared with the real work of education which took place on the campuses and in the classrooms.

(Way back in my college years at Syracuse U., I had taken a course in the area of Industrial Sociology. Looking at these years in GMHC now with what remains of the insights I gained from that course, this transformation of GMHC seems quite typical and unremarkable from a textbook viewpoint.)

It is lamentable, though, that the organization seemed to lose respect/confidence in the value of its grassroots and they for it. A more reflective (and humble) look at the spirit of gay comradeship of the early years would have been salutary during this era of change. And something as simple as a cadre of a dozen volunteers doing informal and no-bullshit style PR and spreading information on the streets and in the bars might have made a positive impact too. However, time is an inescapable steamroller, and as the earlier ranks of volunteers thinned considerably from death, burn-out and the need attend to personal commitments, the later volunteer recruits who replaced them accepted the changed organization as they found it. In part this may have been due to the fact that a larger number of the new volunteers were straight women unfamiliar with the earlier GMHC.

In the mid-Eighties City officials had been publicly saying that they shuddered to think of what would have happened in New York if gay men had not formed the Gay Men's Health Crisis and other organizations to care for the sick, educate the public and lobby for attention and funds. And under Richard Dunne's leadership GMHC had developed new approaches in response to the changing nature and scope of the epidemic. It expanded services to provide recreational opportunities and an in-house meals program for clients, and to inform them about experimental therapies and promote these therapies. It also developed a more active public face in a big way. GMHC began to lobby city, state and Federal agencies often to good effect, and it was very active in creating and disseminating accurate information about HIV/AIDS particularly important in light of the virulent homophobia and fear of AIDS unceasingly manufactured by political and religious spokesmen.

Richard Dunne resigned as Executive Director at the beginning of September '89, and he died of AIDS-related causes at the end of December the following year. His obituary in the New York Times gives very specific information on the great changes in the organization during his leadership.

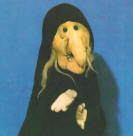

THE AIDS SPECTACLE

The charnel house atmosphere that had settled down over gay

life in New York is what I remember most clearly the nauseating stench of shit

and puke combined with the piercing, tear-inducing odor of chlorine

disinfectants, a shaded light next to someone sitting a death watch, ravings of

the demented...closed bars, closed stores, empty apartments...ravaged faces and

corpselike bodies...the unceasing spew of Evangelical Christian hatred from

television and Usenet, and the homophobia and obstruction of New York's

Cardinal O'Connor. And then on the other hand, there was a tiny fringe of

HIV-deniers, a handful of medical people who continued to maintain that HIV was

not the cause of AIDS, and then the the conspiracy theorists (still around) who

ferociously maintained that the government had introduced AIDS into the gay male

population as an experiment during the research for a Hep B vaccine.....and the

incredible weariness of trying to not give up and fold in the face of what

seemed like a madhouse.  "Seemed", bullshit. It was a madhouse.

"Seemed", bullshit. It was a madhouse.

The crucial political battles and the desperately needed medical breakthroughs, and the pivotal, transforming activism of ACT UP in Washington sometimes seemed like bulletins from a distant front coming back to a city under a blitz.

17th cent. "plague doctor"

It was a kind of midway of desperate hope, bizarre promises and outright charlatanism The AIDS Spectacle of researchers, activists, conspiracy theorists, demagogues, good guys and bad guys, gurus and poster boys...chemical cures, talismans, herbs...creeds and messages, and healing crystals and books...and tapes, tapes, tapes cranked out by every channeler of spooks from other spheres and self-anointed healers. Empowerment and quackery were hawked with equal vengeance. And it must have been to some of the public as entertaining and mind-boggling as the public tours of Bedlam madhouse were in the early 1700's.

My life during these years was taken up with

caring for friends, and being a Crisis Intervention Worker (CIW) volunteer for GMHC. These activities

became a second job, and my contact and involvement with other organizations was

minimal. As I said above, what else was going on in this era often had

the quality of news from another front. For that reason I have put

information and anecdotes about these groups together on a sub-page, and here

and there in the main pages there are internal links that will take the reader

to sections of it. If you wish to check out that page from the beginning

(it has material about the PWA Coalition, Michael Callen, Louise Hay, Marianne

Williamson, ACT UP, "innocent victims" - the Ray brothers, Ryan White and

Kimberly Bergalis, etc.) the following link will take you to the top of that

page (use your browser's Reverse arrow to return to this point):

The AIDS Spectacle.

CHUCK - 1987

This human form, his friend's....was foundering under his eyes in the dark flood of pestilence, and he could do nothing to avert the wreck.

Albert Camus

The Plague

My best friend Chuck and a mutual acquaintance, Billy, who was a close friend of his were working together in '83. Both were "not feeling well" with similar complaints; finally they bolstered each other's courage and went to an HMO on West 79th for an examination and blood tests. (There were no tests specific for the HIV anti-body at this point.)

The doctor assured them both that there was no reason to believe that they had "it." However, both continued to be bothered with various symptoms. Billy decided after a while to go to another doctor, Chuck wasn't interested. This time Billy was told that he was definitely symptomatic for AIDS. Chuck angrily refused to see a doctor, and seemed to resent Billy's second visit and what it disclosed. When I saw Billy in October '84 he looked good. Billy was sometimes called "Billy Sunshine." He was quite tall and had a head of thick, very curly golden blond hair I could always spot him on the crowded rush bus we both took across 79th Street and although he was sometimes a bit shy, he had a wonderful grin, which reflected his disposition.

Billy

left the city and went back to the Boston area where his mother and

sisters lived, and where he could get medical treatment as good as he could get

in New York. He was down on a visit to Chuck a year later, and I stopped over. He

had lost weight and was pale, but most startling to me was the Hickman line

hanging out of his chest. (The Hickman central line is a tube or catheter

placed into a large "central" vein close to the entrance to the heart for

patients who need repeated and long term IV medications) He was sitting on

the couch, I knelt in front of him and held him. A month later he was dead.

Billy

left the city and went back to the Boston area where his mother and

sisters lived, and where he could get medical treatment as good as he could get

in New York. He was down on a visit to Chuck a year later, and I stopped over. He

had lost weight and was pale, but most startling to me was the Hickman line

hanging out of his chest. (The Hickman central line is a tube or catheter

placed into a large "central" vein close to the entrance to the heart for

patients who need repeated and long term IV medications) He was sitting on

the couch, I knelt in front of him and held him. A month later he was dead.

His mother and sisters came down to New York at the middle of the month for a memorial service in Chuck's apartment. The number of people crowded into the place must have pleased his family, and that fact that many of them were not younger people Billy's age (he was in his late twenties), but middle aged people that he had worked for or known. I had made a music tape Chuck asked for, and the "service" consisted of people recounting anecdotes about Billy, or reading selections that reminded them of him.

One man read ee cummings' poem on Buffalo Bill, which ends with the line:

Several people gasped.and what i want to know is how do you like your blueeyed boy Mister Death

When everyone who wanted to had spoken, one of his sisters talked about a notebook that Billy began keeping after he returned home. I had not known him as a studious sort of person or even very introspective, but his journal showed a curious and courageous individual looking at his life and oncoming death. Some of what he wrote suggested he may been reading about Gnosticism and the Persian Muslim mystic Rumi. She read one of the last entries, perhaps it was the very last. I have unfortunately lost the copy I made, but it was similar to this translation from Rumi that Karol Szymanowski used for the vocal part of his Third Symphony: Song of the Night.

I and God, alone together in this night!

What a roar! Joy arises,

truth with gleaming wing is shining in this night.

In the months after Billy's death Chuck became almost a recluse and very unwilling to talk even on the phone. It was impossible to know how much was "not feeling well," and how much was depression. Finally, one day late January '86, he surprised me when he telephoned to say he was dropping over, and when he showed up he was in a much better mood than he had been for a long time.

By early June he was full of his usual piss and vinegar again, and out of the blue he gave me what was nothing less than a glowing tribute for "all your support for a year and a half." I was really flummoxed by this! Much of our contact during that time had consisted of telephone calls or visits marked by long, excruciating periods of silence, during which I desperately wanted to be anywhere else but where I was. I had come to fucking dread getting in touch with him. I certainly appreciated what he said, but I felt a bit guilty because what he had felt as "support" I had experienced as something I had dreaded...a feeling that I was, in fact, failing him.

In late July he went on a short selling trip to the Hamptons, when he came back he said he was feeling horrible again. After six weeks of delay seeing a doctor, he had an appointment and was diagnosed with chronic active hep and anemia in late September. My life became frazzled. My first GMHC client, Kevin, was declining at this time, and Chuck's health continued to get worse. Just as my Kevin died, Chuck had to go into the hospital. Once back at home his life shrunk to his apartment again. He was often overcome by lethargy and nausea, but then sometimes he had brief periods of feeling better or at least "better" relative to feeling shitty. (Having experienced a prolonged period of what was diagnosed as autoimmune hepatitis, I did not question the diagnosis he received for his symptoms.)

The bottom fell out in February '87. I had accompanied him to the hospital for a test he was diagnosed with CMV (cyclomegalovirus,) a member of the herpes family which can attack the linings of internal organs or the optic nerve. To me this had to mean AIDS. He was hospitalized, and the next day he emerged from a discussion with the doctor looking horror-stricken. The doctor had said it AIDS.

Chuck was in the

Co-op Care unit of NYU Medical Center. This is a special facility where you stay

in a hotel-like room, eat in a common dining room and go to a treatment floor

for many of your procedures providing you have a live-in care partner or

partners with you during your stay.

Chuck was in the

Co-op Care unit of NYU Medical Center. This is a special facility where you stay

in a hotel-like room, eat in a common dining room and go to a treatment floor

for many of your procedures providing you have a live-in care partner or

partners with you during your stay.

(right) NYU Medical Center

Wayne (a friend Chuck had taken as a roommate to help stretch his money), Matt (an old friend of Chuck's who just kind of showed up out of nowhere) and myself took turns staying with him. Several weeks later he was released and had to have daily visits from a nurse from the Visiting Nurse Service (VNS.) His nurse, Barbara, was terrific, and she clicked with Chuck immediately.

When he was released and back home, he called me over one day. He abruptly announced that he had given me his general power-of-attorney, as well as his medical power-of-attorney, and I was to be the executor of his will. Furthermore, he wanted to take any cash he had in the bank and open a joint account in both our names so that I could write checks to cover his expenses if he could not. I was used to Chuck's peremptory way of dealing with people, and his streak of almost indomitable stubbornness. This time, however, I sensed he was springing things on me without any discussion out of fear I might refuse rather than from bossiness.

I accepted, of course, though I started to say that I wasn't comfortable about the joint bank account aspect of his plans. But he suddenly leaned toward me and grabbed my hand, and tears ran down his face. "Please promise me ," he pleaded. "Keep me at home."

Tom, my roommate, asked me to ask Chuck if he could come over to visit. They had once been good friends, until Tom had caused a rupture in their relationship by walking out on a job with Chuck's boss without saying so much as a kiss-my-ass as soon as he got his first pay check. It was Chuck who caught shit for this stunt, of course. Tom had never apologized, and they hadn't spoken for years. Chuck was quiet for awhile before he answered my question, then he said, "Tell him no, the time for him to talk was three years ago."

It was mid-April when I realized that I couldn't juggle physically or emotionally my GMHC client at the time ( Ralph + his crackhead girlfriend) and Chuck. I took a leave of absence from being an active CIW volunteer.

Two days later Chuck was back in the hospital: pneumonia this time the lung-shreddng pneumocystis carinii. After almost a month things are looking up; they are telling him he will be able to go home in a couple of days.

When I go back the next day catastrophe! Enormous changes at the last minute. Instead being homeward bound, they are going to remove his left eye! Like what? The CMV had infected it, and since he would soon be totally blind in that eye they want to remove it ASAP in hopes that the infection will not travel up the optic nerve to the other eye. His vision had always been lousy, and he wore a very strong prescription, so this meant that his remaining vision would be very poor.

This is probably the appropriate time to mention Chuck's doctor, the thus far unmentioned man I shall call Dr. X. He was a specialist at the hospital who had been called in on consultation early on; and by virtue of his area of expertise and the fact that he had an office on the Upper West Side, Chuck picked him to be his personal physician. The nursing staff were very contemptuous of Dr. X and their demeanor was so cold when he engaged them it was like watching the iceberg approaching the Titanic. One of the nurses told me that when Dr. X had first begun dealing with AIDS patients he used to stand in the patient's doorway in full hospital drag, including a mask, talking to the patient from a distance, while all the time nurses pushed past him, going in and out to deal with the patient's needs. I found him very remote the two times I saw him with Chuck. The woman who was Chuck's personal GMHC volunteer took him to Dr. X's office for his rare visits and was present during the consultations, she told me that the visits were extremely brief, and that he never discussed Chuck's treatment with him but simply gave him terse orders and dismissed him. I suggested to Chuck that he should consider changing physicians. He angrily refused to even discuss his relationship with Dr. X.

Why, when there were many doctors gay and straight who were well thought of by their patients did he stick with this "uncommunicative" man? I never really found out, but over the time of Chuck's illness some things came out which may have pointed to why: For one thing, medical information seemed to terrify Chuck, so the less the better. (And this had been his attitude, though not Billy's, when they both first went to a doctor together.) And then one day, out of the blue, he began sobbing when we were in his apartment talking. He said that he had been never appreciated how much Billy had suffered until now, he had been unsympathetic and hard on him when he was sick! I got the message that Chuck might have felt that his misery was a kind of pay back. (I had had just a couple of fairly brief visits with them together after Billy had become ill, but nothing I saw or that Chuck said to me during that time prepared me in the slightest for Chuck's "confession.") I have continued to think that under the pain and pressure of his own illness he might have been misjudging things with Billy very badly. Finally, there was the fact that Chuck was strong-willed and could be a bully. One prolonged standoff between Chuck and I several years before had shown me that he would only get hold of his overheated emotions when he was faced down with an iron will. Maybe he needed Dr. X's brusque, authoritarian manner to keep a grip on himself just shut up and obey.

Except as the occasional dispenser of prescriptions, Dr. X. really was a non-player. I thought of him more as the asshole in absentia.

The one thing Chuck had held onto between his aborted release and the loss of his eye was the offer by a friend to use his room in a house in the Pines for a week, if he was able. Chuck had vowed he would be able, and I had promised to go with him if he was...convinced that it could never happen. He was released in late May, and in a month at home he slowly regained some vigor. Now it's D-Day, and we are heading for the Island.

Chuck has a Hickman line implanted in his chest by now, and we are carrying more IV bags than luggage. But we go. And a voice in my head is saying, "I don't fucking believe this. Who do you think you are? The Lone Ranger?"

After we arrive, while Chuck is resting, I sneak off to the doctor to check out the lay of the land in case of an emergency. (The community customarily gave doctors the use of a house for vacation time in return for their holding office hours while they were out there.) I go in, we shake hands and I sit down across the desk from him. This particular doctor was so straight he smelled like a yardstick. As soon as I mentioned being there with a friend who had AIDS, he gets up from the desk and goes to stand on the other side of the room, leaning against a file cabinet. I sniffed under my arms, certain that I must have suffered sudden and massive deodorant breakdown. All I wanted was info on emergency resources, in the unlikely event something super-bad should happen; all he wanted was for me to get off the Island with my friend - NOW! Now, please...now, now, now, he urged. He was obviously terrified that he might be called upon. The visit was obviously pointless; so I left, with our medical stalwart on the verge of pissing his pants.

This visit did make me a bit contrite, as I considered that Chuck's doctor in the city was possibly not the biggest asshole with an M.D. after his name.

However, there was an angel waiting. The house was large, with a pool, and was shared by two owners and two (or three) other guys. Plus there was an additional roommate, Mike, who had a room for the summer in return for being a sometime "houseboy." He was a good-looking, well put together guy just under his mid-twenties and he had never spent any time with someone with AIDS I was to learn later. Except for Mike, the other occupants had already departed to the city for the week. Aside from introductions Chuck and I spent the evening alone the first night. The next day Mike came in to talk while I was in the kitchen making sandwiches the poor guy was clearly walking on eggs, not sure what to do, what to say...etc. At some point I went for a walk, and when I came back Mike was sitting and talking with Chuck, who had moved to the living room to lie next to a heater. He watched while I hitched up the IV, and was (understandably) taken aback when Chuck lifted up his shirt and he saw the Hickman line hanging out of Chuck's chest. The next time, he said, "Show me." The fucking doctor can't get far enough away, and this young guy is saying, "Show me." I felt a pain in the gut like I was going to burst out crying. And from then on, except to sleep, he hardly left Chuck's side. Chuck was not holding up well, and stayed on a chaise lounge in the living room by the stove, even sleeping next to it.

A few times when I got up in the middle of the night to check on him, I heard him and Mike talking. Mike insisted on taking us out to dinner. Shortly after the meal began, Chuck vomited the food he had just swallowed into his napkin. He ceased trying to eat, Mike and I finished quickly with awkward conversation. Late Friday afternoon Mike saw us off at the ferry, and we waved to Chuck's friend who was just arriving for the weekend. We boarded the ferry. It chugged around and headed slowly to the entrance of the harbor, as we passed out into the bay Mike was standing alone at the harbor entrance, waving goodbye.

(Even now, decades later, I could cry when I remember this guy. I hope that he has lived a long, happy life.)

I have said that 1985 was the last of my years twenty-five years of going to the Island. And it was. In no way was this week a part of those years that preceded it.

I was still doing Client Intake interviews for GMHC (one of the interviews was with a guy who had been a Sunday night dancer at The Saint like myself), and I was acting as team secretary. But these activities seemed like a furlough from what was now my "real life." For the rest of the summer Chuck was better than he had been on the Island. Tom came to his terrible end in July, and I had to tell Chuck. Chuck sat down and with some help was able to slowly and carefully write a note to Tom's sister, whom we both had known, even though he could now barely see with his remaining eye.

Late in the spring Gino had gone with me when I stopped in to see Chuck, despite working for GMHC he didn't see people in Chuck's condition coming into the office. He began to cry on the stairs as we left. As Chuck took up more time in my life, I sensed a change in the relationship with Gino. Sometimes I felt that he was treating me with a strange kind of "politeness." In August it became clear why: he ended our relationship because he had started one with someone else he met on a holiday shortly after I had gone to the Island with Chuck.

Chuck began to slide rapidly down hill. He said the light bothered him, and he had Wayne nail black cloth over all the windows now once you entered the apartment there was no outside world. Chuck was practically blind in his remaining eye, he developed a huge ulcer in his mouth, and at one point he didn't even have the stamina to take the entire four units of blood he is scheduled for at the hospital.... On one visit we could only hold each other. Another day when I thought he was too tired to talk, he said, "I am weak not tired I can listen." He was no longer always aware when he was urinating or defecating. I got plastic sheeting and diapers from Alan, who had been a neighborhood pharmacist as long as I could remember. A fine man, and a kind one to many gay men in these years.

October 18th, coming home late from Chuck's, I wrote:

"At last I see Chuck dying, and I feel in myself his dying for me. He is in pathetic condition: practically physically helpless, devastated with fever attacks, too weak to be able to take care of his basic needs, BUT totally free of any outside concerns or hassles, no anger now. Clinging and filled with gratitude for the smallest things."

One Saturday morning, just as his sister from the suburbs arrived to visit, Chuck pitched into a crisis. Barbara the VNS nurse and I had to call an ambulance when his doctor didn't answer our emergency call. Chuck and his poor sister and I had a Wild West ride to Beekman Downtown Hospital at the bottom of Manhattan. He rallied. In two days Chuck checked himself out of the hospital, and the doctors called me at work, telling me he's dying, there's nothing they can do for him that the three of us can't do.

I had started hiring home health care workers just two days before this happened, and swung into high gear on that again. I told the agency that a "candidate" had to pass three tests: Chuck had to like them, they had to be able to deal with the turnstile appearances of the three of us, and they had to be willing to let Chuck do absolutely anything he wanted that was not going to cause immediate harm or pain to himself. The acid test turned out to be sitting on a kitchen chair in front of the open refrigerator door with Chuck for an hour, while he held your hand and rhapsodized over the beauty of ketchup bottles, tuna salad leftovers, yesterday's soup, Chef Boyardee spaghetti cans, etc. a kind of Andy Warhol meets Steven Levine approach to death and dying.

And such people

did exist: first, Ruth full of razzmatazz and good humor (Chuck called her

"Pearl" because she reminded him of Pearl Bailey, and sometimes I think he

thought she was her); then Betty solemn,

agreeable and imperturbable. And, finally, the woman we were waiting for, the

magical if somewhat far-out Rosa. With these three incredible black women

the day was covered. Wayne lived in the apartment, and Matt and I started

staying overnight off and on too. One Tuesday night he toured the apartment, as if

in a trance, sometimes seemingly not aware of us at all, picking up objects

talking aloud about what they were, sometimes talking to them.

And such people

did exist: first, Ruth full of razzmatazz and good humor (Chuck called her

"Pearl" because she reminded him of Pearl Bailey, and sometimes I think he

thought she was her); then Betty solemn,

agreeable and imperturbable. And, finally, the woman we were waiting for, the

magical if somewhat far-out Rosa. With these three incredible black women

the day was covered. Wayne lived in the apartment, and Matt and I started

staying overnight off and on too. One Tuesday night he toured the apartment, as if

in a trance, sometimes seemingly not aware of us at all, picking up objects

talking aloud about what they were, sometimes talking to them.

"He's saying goodbye to his home," Rosa said.

From that night on he was delusional most of the time. Thursday he said at one point, as if it were a comment about the weather, "I'll last two days." Late on Friday night, the three of us were there and Rosa too. His bedroom opened through an arch onto the living room. He asked for music, Keith Jarrett's Kφln Concert. In fact, he insisted on it it played all night on auto-reverse; every time we stopped it, thinking he was asleep, sooner or later he would say he couldn't hear it. He got up, carrying his pillow. He wanted all the lights out. We lit a couple of small votive lights to be able to see each other. Later he went and lay down on the floor, blocking the front door of the apartment. We covered him with blankets and gave him a pillow, for awhile we lay down beside him and then we and let him stay there. Not too long after he woke up, and we got him back in his bed.

Rosa had seemed a most unusual person with a very streetwise manner in some ways and she handled Chuck perfectly, no matter how sunk in delusion he was. She had asked a lot of peculiar questions of each of us and had made some disturbing observations, all of which seemed to point in the direction of something psychic, for lack of any other appropriate label. I found out she had a "sanctified church" background, but had left to be out on the street where she found less "calling down" of people and more "teachers" in unexpected persons. Several times during the night she began to tremble violently, and spoke in an awed voice of powers coming and going in the room. I sat beside her, thinking, and decided that I had failed Chuck: I had been postponing the natural and merciful end that I had promised he would have. Tomorrow, after the nurse came, I would stop all IV medications and hydration.

At that very moment Rosa seized my hands in hers, and shouting, said, "Your hands are going to do great things!"

It scared the piss out of Wayne and Matt, and I really could have used a cup of Valium just then.

Waves of incredible tension and calm alternated all night and that fucking music never stopped. From time to time we would creep over to the door to see if Chuck was still alive, and then hold his hands for awhile. At dawn it was Halloween he abruptly got up, walked into the living room and lay down on the couch.

The Visiting Nurse, Barbara arrived, she did her stuff, and then I called her into the dining room to talk. I was "taking over" the medical decisions, I told her, as I had the Medical Power of Attorney and Chuck was clearly not competent. I told her that I had decided to terminate all mediation and hydration. Rosa left, Betty came and we sent her to the laundry with the last of the sheets. I asked Barbara to call the VNS supervisor, who could not have been cooler and nicer, I asked VNS to call Chuck's doctor (as I hated his guts, though he seemed to have none.) Chuck was completely incontinent but it was all blood and tissue, he was lacking platelets. Barbara said goodbye. I unhitched the IV, and we sat there. After awhile I took his pulse. There was none. When Betty came back we asked her to come and look at him. She stopped at the doorway and looked in. "He be dead."

After some time to collect ourselves, we got busy. Then the phone rang. It was Chuck's sister calling from the airport, where she was meeting her parents who had come up from Florida I had to tell her that her brother had just died. Wayne went from window to window, pulling off the dark cloth coverings that had been stapled to the frames, and throwing them open. The funeral home had to be called, and then the doctor, who had to agree to sign a death certificate before they would come to pick up the body. Wayne and Matt crawled out the living room window and sat in the sun on the roof over the building entrance. Barbara, the VNS nurse, called to see how Chuck was doing. Rosa called she said, "I knew he would go today."

I heard Wayne shouting my name from the other room at the top of

his lungs. I ran in. He was horrified. We had not pulled the

blanket up over Chuck's hands and face. Flies had come in through the open

windows while we were doing other things, dozens of them covered his face and

were crawling into his ears and nose.

I heard Wayne shouting my name from the other room at the top of

his lungs. I ran in. He was horrified. We had not pulled the

blanket up over Chuck's hands and face. Flies had come in through the open

windows while we were doing other things, dozens of them covered his face and

were crawling into his ears and nose.

LOST

A

month after Chuck's death on October 31, 1987, all of the busyness that comes

with death the funeral, paying bills, lawyers, breaking up a home was pretty

much out of the way. I had moved out of the old Upper West Side neighborhood

earlier in the year after twenty-seven years there a part of

the gay attrition

caused by the death and disruption of the epidemic. Matt lived north of NYC

in the country, and Wayne had decided to move up there with him, these were the two

other guys who had helped take care of Chuck. I was now in a

furnished studio apartment on the top floor of a (literally) crumbling Federal

house right off Stuyvesant Square, just a bit north of the East Village.

View of part of Stuyvesant Square.

It was a historic and very pretty patch of the city, though after dark the park was populated not only by dog walkers, but addicts and dealers too, and some nights you could hear burglars walking across the roof and testing the trap door on the roof which opened onto the top floor.

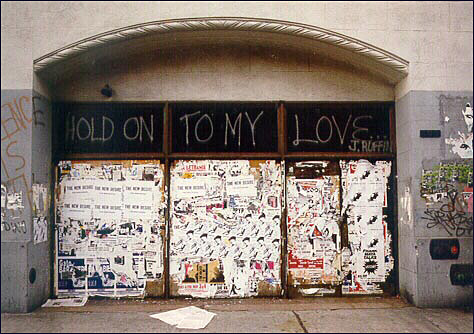

Anti-gay graffiti had popped up around town after the

"Disco Sucks" riot. On my rare daytime trips to the East Village I had

thought there was more there than elsewhere, which I attributed to the fact that

the neighborhood attracted many young white visitors. "Hate gays" and

"kill fags" seemed to have become the latest graffiti fad. With the epidemic, scrawlings about "AIDS fags" had joined the hate parade. Now that I lived

in the Stuyvesant Park neighborhood I was often in the East Village, or I often

went

down Bowery to Chinatown.

Anti-gay graffiti had popped up around town after the

"Disco Sucks" riot. On my rare daytime trips to the East Village I had

thought there was more there than elsewhere, which I attributed to the fact that

the neighborhood attracted many young white visitors. "Hate gays" and

"kill fags" seemed to have become the latest graffiti fad. With the epidemic, scrawlings about "AIDS fags" had joined the hate parade. Now that I lived

in the Stuyvesant Park neighborhood I was often in the East Village, or I often

went

down Bowery to Chinatown.

Chinatown

I saw that the homophobic graffiti was thickest around the area of CBGB, a famous rock club on Bowery I used to wonder how many of the punk rock customers would have liked to bash me. Each time I passed that area it felt like the place made bad juju!

CBGB punk rock club

Gino made attempts to be supportive, but his new relationship was already proving a contentious one, and by nature he was very fearful of any emotional deep water besides. Our phone calls and occasional visits really hadn't much substance. I was rapidly drifting into psychologically bleak terrain. I was physically and emotionally lethargic, sleeping or just lying under the covers in a numbed out state of mind, as often as I could.

One weekend late in November I thought a lot about Chuck, not the time he was ill, but the many years before. I wrote down how much he had helped me, and ended by saying, "He is the person I would go to now, but that is part of what I have to come to terms with."

A few days later I wrapped up a half dozen things in brown paper and put people's names on them, just small things I'd had for the past few decades. The next night I took out a large bottle narcotic painkillers, plus some stomach tranquilizers, that I had taken from Chuck's place when we cleaned up. I called up Wayne in the country, and in the course of a wandering conversation, we suddenly fell into the middle of what had been going on with me. And though I didn't say exactly what point I had reached that night, he hit on the right on track and provided enough impetus for me so that I put that stuff away when I hung up. I lay awake all night; there were no great changes with the sunrise, it just seemed a matter of having the will to plug away with what was at hand. But I still did not have that will.

However, what was most "at hand" was obvious.

I told GMHC that I was ready to take another client. In truth, I was probably no more "ready" for that than I was to be midwife to a whale. But I was relatively healthy and able at a time when thousands of gay men were dying; it seemed shameful now (even evil, perhaps) to throw that away when so many others around me were perishing.

For

a little while I did feel better about

where I found myself,

when I had thought I might read myself out of it. I started by returning to

the Meister Eckhart book I'd bought a decade and a half ago, and then that

seemed to point to another Medieval mystic, Hadewijch the Beguine.

For

a little while I did feel better about

where I found myself,

when I had thought I might read myself out of it. I started by returning to

the Meister Eckhart book I'd bought a decade and a half ago, and then that

seemed to point to another Medieval mystic, Hadewijch the Beguine.

Beulah Witch, not Hadewijch

(Her name almost always conjured up the image of Beulah Witch from the 50's Kukla, Fran and Ollie TV show!) And from there briefly to a fellow named Ruusbroeck, until I lit on an anthology of Friends' writings. John Woolman and Thomas R. Kelly may have had something to say that I was really capable of grasping. And then something there pointed me toward Ouspensky a difficult read, to say the least, and I only made it about a quarter of the way through one book. (Good grief, please don't blame the Friends for this. I have been at a loss for years to find what it was in that reading which led me to Ouspensky.)

But this "uplifting" reading wasn't really doing me as much good as I wanted. Of course, what I wanted was a "magic pill" that would make me feel "all better," and I was working a con, trying to make myself believe that this esoteric reading would produce an equivalent effect. However, I wasn't together enough to realize (or admit, probably) that I was resorting to this spiritual reading program with a hokus-pokus attitude more appropriate to astrology.

I had neither the aspirations, nor the grace of these people I was reading and in the case of the Medieval mystics, especially, not their belief in a God either. All too often I found myself, particularly with Hadewijch wilfully twisting meanings to fit my own dealings at a very mundane and selfish level.

And yet I didn't doubt the truth, whether it was about Divine Love or human love, that one is only fully committed to the beloved if you are ready to give him/it up. That struck a resonant chord, at least, in that whether it was Chuck with AIDS or the port-in-the-storm relationship with Gin: this was at the crux of the matter. I did ignore with determined effort, though, the acceptance of desolation which mystics were also emphatic about. Hadewijch was particularly annoying in this respect, and I finally decided that she was entirely too smarmy to deal with and needed to be put in her place which was back on the bookshelf! But then, she and the rest of the Medieval cohort were having ecstasies over an ineffable Divinity; whereas, truly, I believed in the substance of these not at all. Clearly, I was not in their league in more ways than one.

However,

I wasn't ready to give up on my

spirituality-for-an-atheist reading program. I had gotten bogged down with Ouspensky, who while interesting, was a pisser to read. In discussing his own

thoughts, he made remarks several times to the effect that the Buddhists had

gotten it almost as right as he did. Finally after one tough read, I thought, well, if they only "almost"

got it, maybe they are only almost as enervating to read. I browsed around

the old Weiser's book store on Lex and 24th, and picked up a copy of what

looked practically like a Buddhist primer, What the Buddha Taught by

Walpola Rahula.

However,

I wasn't ready to give up on my

spirituality-for-an-atheist reading program. I had gotten bogged down with Ouspensky, who while interesting, was a pisser to read. In discussing his own

thoughts, he made remarks several times to the effect that the Buddhists had

gotten it almost as right as he did. Finally after one tough read, I thought, well, if they only "almost"